The summit of Everest! The view is exceptional, as are the emotions that are surging through me. Such beauty! What a divine gift to be here, high on the highest mountain on Earth, among these icy sentries. I have finally realised my childhood dream; I have a new lease of life, I am reborn.

Since my return from Nanga Parbat in February 2018, this has been the project I have clung on to. Everest is what has taken hold of me, kept me alive, despite the black chasms of despair into which I have so often sunk.

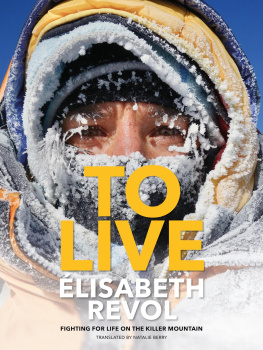

I had finally gone back home to the Drme. After two days in an Islamabad hospital, I had arrived in France on 30 January 2018. I then spent an exhausting week of intensive care in hospital in Sallanches, where I was stormed by the media. That was followed by a press conference in Chamonix on 7 February, as I was just coming to realise or rather admit that there was no longer any hope of saving my climbing partner Tomek; where, despite being exhausted and in shock, I had tried to answer questions. Doctors had requested a further assessment of my frostbite in six weeks time.

During this recovery period, one of my sponsors, the founder of TeamWork Voile et Montagne, Philippe Rey-Gorrez, visited me. He asked me which projects remained close to my heart. As a girl, I told him, I had dreamt each night beneath a poster of Everest. 2 This mountain was my first dream, the root of my passion. In May 2017, I had spent two perfect months in the Himalaya, wandering among the giants of our planet visiting Makalu, summiting Lhotse and then confronting Everest, alone, without oxygen. My heart fluttered with the euphoria and joy of finally treading on the flanks of this mountain! But at around 8,400 or 8,500 metres, a blizzard and extremely cold temperatures convinced me to give up. Returning to Everest would be financially challenging; my dream would remain unfulfilled. The day you decide to go back to Everest, Philippe Rey-Gorrez told me straight, Ill be there to help you. You can explore the mountain without oxygen, but with backup: someone to follow you with oxygen in case you have a problem. A rush of warmth ran through me, a burst of life that softened my heart, which until this point had been hardened like a stone. Hearing these words, I imagined myself at the Icefall in an instant. I saw my bivouac at Camp 4 under the twinkling stars and the beautiful full moon. I imagined myself on the Hillary Step, breathless and slow, but brimming with emotion. Our meeting was brief and informal, but this project lit up the depths of my despair and, for the first time since my return to France, I glimpsed a ray of light

It was this idea that brought me back to life; I thought about it all year. I discussed it immediately with Jean-Christophe, my husband, and with Ludovic Giambiasi, my best friend and personal route planner. I told them that the one last project close to my heart in my life as a Himalayan mountaineer was Everest. I thought about it each time I found myself spiralling downwards, drowning in a hell of guilt and bitter memories.

One year later, in April 2019, I left for the high mountains again, heading for the Baltoro glacier in Pakistan, the land of thin air that has held a magnetic attraction for me since I first discovered it in 2008. As I packed my bag, I was rattled by contradictory emotions: joy, a feeling of freedom, a sense of taking revenge on the previous year, a conviction that it was now or never. But also plenty of nerves 3 and fear, relating to me: my capacity to bear the cold in my fragile extremities, my capacity to return to the high mountains, to go back to high-altitude bivouacs, with my memories of people dear to me who had touched my life and left too soon.

I am addictedto the mountains. I have been acutely aware of this since my return from Nanga. Previously, on my return from Annapurna in 2009, I had gone through a dreadful phase of questioning, of doubt. When you are defeated, you interrogate yourself about the irresistible attraction that constantly draws you up there. You also come to understand that youre caught in a trap.

I was twenty years old when I caught the climbing bug. I binged on summits. I ascended many routes and faces in the Alps over a period of ten years. I was looking for difficulty and performance. Effort, elevation, excitement, stress, questions, then fulfilment this cocktail satisfied me a little more each time. When I discovered the Himalaya in 2007, an infinite universe of exploration opened up to me: discovering new summits, but also testing my aptitudes and my limits in the troposphere.

Even though I have lived through some terribly difficult, unbearable things in the high mountains, my attraction to them remains strong.