About the Author

Jack Ballard is an award-winning outdoor writer and photographer. In the past ten years his articles and/or photos have appeared in over twenty-five different regional and national magazines, including Paddler magazine, Montana magazine, WildBird magazine, Colorado Outdoors , Birds & Blooms , and others. He currently lives in Red Lodge, Montana.

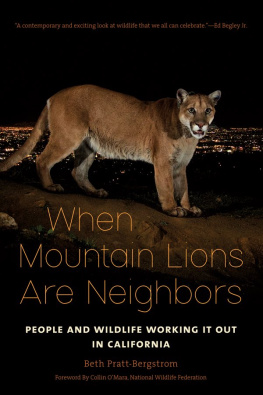

This book is dedicated to the hope that mountain lions may once again roam at least some of their historic habitat in the midwestern and eastern regions of the United States.

FALCON GUIDES

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Falcon, FalconGuides, and Outfit Your Mind are registered trademarks of Rowman & Littlefield.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

Photos by Jack Ballard unless otherwise noted. NPS photos courtesy of the National Park Service, USFWS photos courtesy of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ballard, Jack (Jack Clayton)

Mountain lions / Jack Ballard.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4930-1255-8 (pbk.) ISBN 978-1-4930-1437-8 (e-book) 1. Puma. I. Title.

QL737.C23B2627 2015

599.75'24dc23

2015019778

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Acknowledgments

Much effort has been expended in recent years in mountain lion research. I am indebted to all the researchers who have advanced our understanding of these intriguing creatures. Two reference works were found to be extremely helpful: Cougar: Ecology and Conservation , edited by Maurice Hornocker and Sharon Negri, and Desert Puma: Evolutionary Ecology and Conservation of an Enduring Carnivore . Anyone wanting to better understand cougars would do well to read these works. Special thanks goes to Marilyn Cuthill of Beringia South, one of the leading mountain lion research centers in the United States, for reviewing and making helpful comments on the manuscript.

Swarovski Optics generously provided superb binoculars to aid my field observations of wildlife. Thank you!

Introduction

The cry was startling and chilling. Laden with a backpack and grinding up a wilderness trail with my older brother in late November, we heard what sounded like a woman screaming in a grove of quaking aspens adjacent to the path. Although the noise was new to my ears, I recognized it immediately as the scream of a mountain lion. We camped about a mile up the trail. Remembering that spine-tingling wail, we had a hard time falling asleep that night.

In all likelihood we witnessed the call of a female looking for a mate, as mountain lions may mate at any time of the year. The unnerving experience lingered in my consciousness for the duration of our outing, but I knew we were in little danger from the vocalizing cat. Mountain lions infrequently attack humans. Such incidences are very rareso much so that we were at greater risk of a fatality while driving to the trailhead than succumbing to the claws and jaws of a cougar.

Beyond hearing that eerie call, my experiences with mountain lions, in four decades of tramping the wildlands of America, have been surprisingly few. I have discovered the tracks of cougars on several occasions. I have sighted a mountain lion but twice. A friend and I observed a large male dart in front of my pickup on a mountain road at dawn. The animal paused in the evergreens for a few moments, giving us a clear, but brief view of its massive paws and muscular body. Another time, I caught the outline of four animals on the highway in my headlights before daylight. They appeared about the size of wolves. I slowed in anticipation of a pack sighting. Instead, my headlights illuminated a female mountain lion with three nearly grown kittens. The youngsters continued to romp for a moment, their presence and antics bringing a broad smile to my face. But their mother quickly shepherded them to the roadside, a matron apparently not quite ready to leave her offspring unsupervised.

As I write this while sitting at Chicagos OHare Airport, the image of a seated mountain lion greets me from the tail of a Frontier Airlines plane. It appears a sub-adult, its intelligent amber eyes seemingly captivated by my typing form. Heres hoping this book will similarly captivate the reader with the secret lives of mountain lions, and enhance, if even in small measure, our societys respect and toleration for these enigmatic cats.

Chapter 1 Names and Faces

Names and Visual Description

Mountain lion is the name given to a large wild member of the cat family in North America. The name, however, is somewhat misleading. Members of this species can thrive in deserts and woodlands as well as the mountains. Historically, and in various regions of the country, the mountain lion has been given many other names, including cougar , puma , catamount , and panther . Less frequently the mountain lion has been called the mountain screamer or painter . There is perhaps no other species in America described by so many monikers. The Guinness Book of World Records claims that the mountain lion has the most number of names of any species on Earth. More than forty different names have been given to this feline hunter. In this book, the names mountain lion and cougar will be used interchangeably for variety and in acknowledgement that both terms are often used in scientific and popular literature.

Even the cats scientific name can be confusing. Mountain lions were scientifically named Felis concolor by Carl Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, in the late 1700s. In the 1970s, researchers concluded that mountain lions were not part of the Felis genus, which includes housecats and other small wildcats. The mountain lion now shares the puma lineage with the cheetah and jaguarundi and is scientifically known as Puma concolor , although the former name, Felis concolor , still occurs in some scientific and popular literature. The change in the scientific name from Felis concolor to Puma concolor was officially recognized by the American Society of Mammologists in 1993.

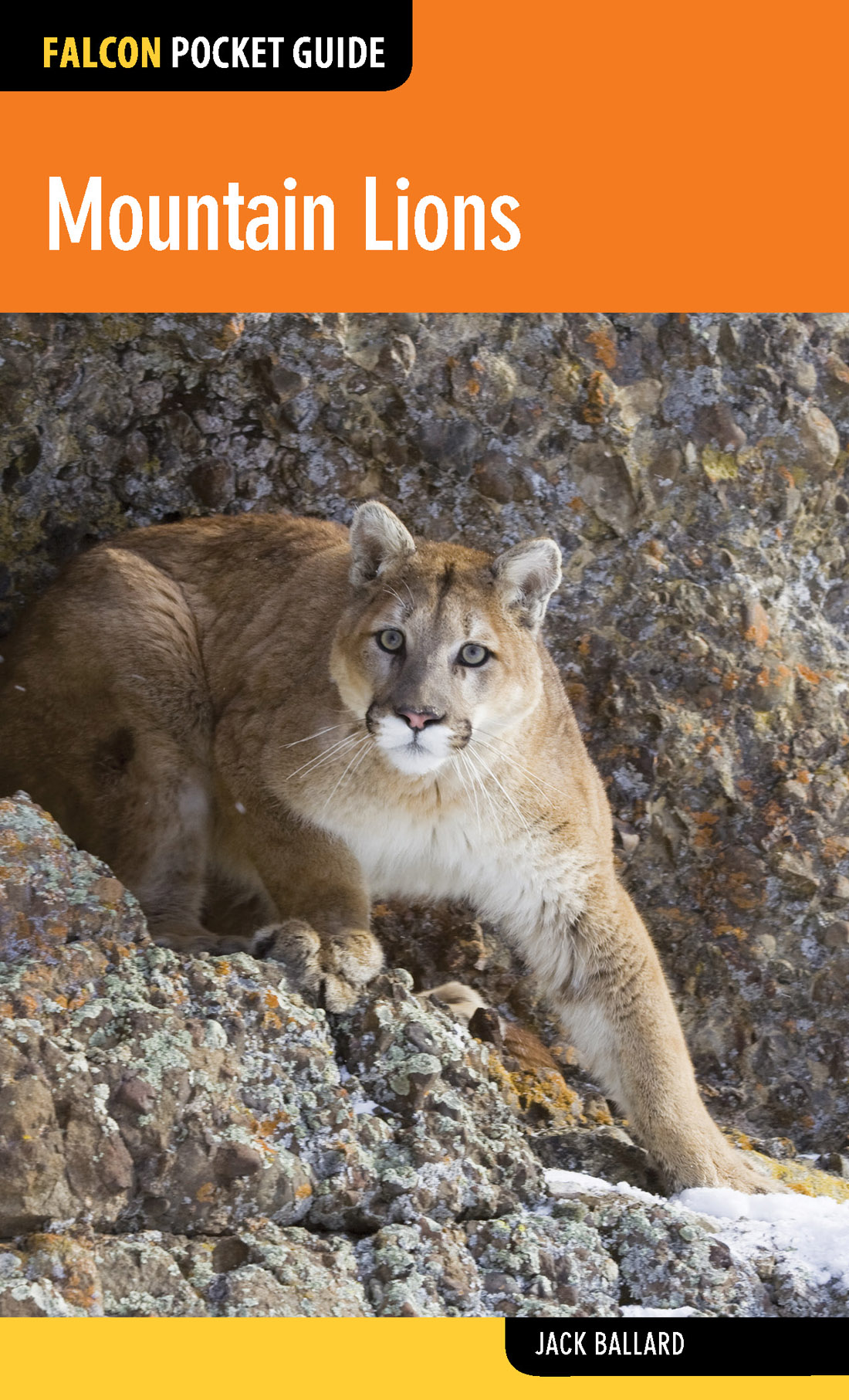

One of the mountain lions physical characteristics can be inferred from its scientific name. Concolor refers to something that exhibits a uniform color. A mountain lions coat displays a range of hues, depending on where the cat is found, but mountain lions are notably uniform in color. The cats shades may range from tawny red to tawny gray to a rich medium brown. Lighter fur typically adorns its ears and cheeks and the inside of its legs and belly. A small black patch of fur is found at the tip of the tail, and the animal sports black stripes or irregular spots on the muzzle, sometimes referred to as a moustache.

Mountain lions look somewhat like an enormous, lean, athletic housecat. Their eyes are large and usually appear yellowish or hazel in color, although very young mountain lions have blue eyes. A cougars ears are fairly short and rounded at the tips. The animals sport a nose pad that may vary from pink to brown (sometimes with black spots) and long, pale whiskers. In relation to its body, the legs of a mountain lion are quite long. Its legs appear rather thick and muscular. One of the most distinguishing physical characteristics of the mountain lion is its very long, full tail. It often accounts for nearly 40 percent of the animals total length, and the cat carries its tail in a drooping or lowered position while walking or standing motionless.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.