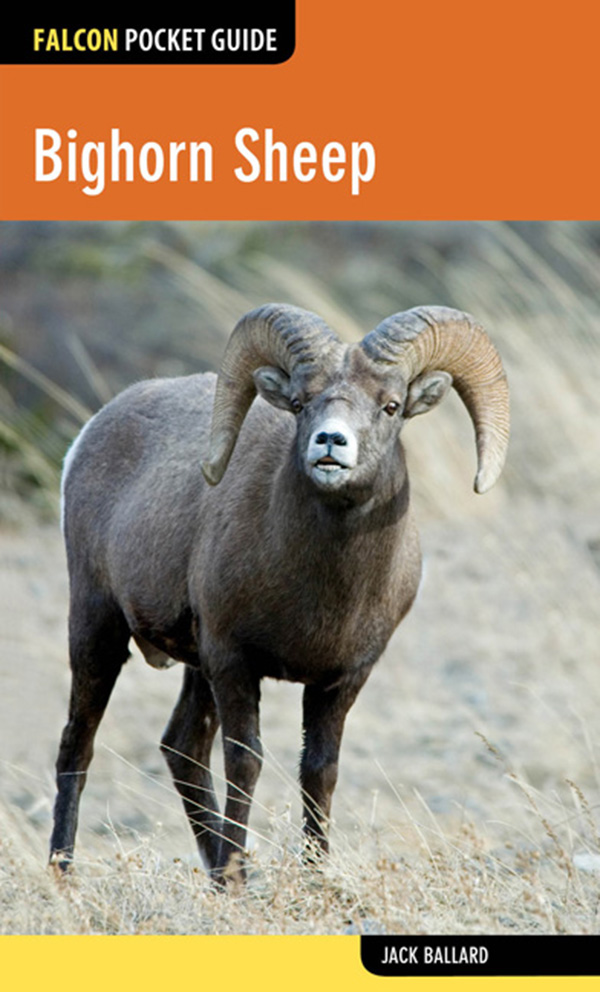

Bighorn Sheep

Jack Ballard

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Falcon, FalconGuides, and Outfit Your Mind are registered trademarks of Rowman & Littlefield.

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield

Photos by Jack Ballard unless noted otherwise.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information is available on file.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN 978-0-7627-8491-2

The author and Globe Pequot Press assume no liability for accidents happening to, or injuries sustained by, readers who engage in the activities described in this book.

This book is dedicated to my son, Micah, our many shared outdoor adventures, and a bighorn ram.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Several wildlife professionals have expanded my understanding of bighorn sheep and provided valuable information for this book and my other writings on bighorns. They are: Dr. Bob Garrott, Professor of Ecology at Montana State University; Shawn Stewart, Wildlife Biologist with the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks; Doug McWhirter, Wildlife Biologist with the Wyoming Game & Fish Department; and Hank Edwards, Wildlife Disease Specialist with the Wyoming Game & Fish Department. I am especially grateful to Melanie Woolever, National Bighorn Sheep Program Leader, of the United States Forest Service for reviewing and making helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Swarovski Optics has generously supplied superb binoculars to support my field observations of wildlife. Thank you!

Introduction

On a November elk hunt several decades ago, my older brother and I found ourselves sliding downward from an exceedingly high ridge on the flank of the Madison Range in Montana. Cresting a bulge on the vertiginous slope, the sight of three animals in a tiny, open basin found us scrambling for our binoculars. My initial impression of the animals assumed a small herd of mule deer, but even before I peered through my binoculars, I knew what they were. Three lordly bighorn rams lounged in the snow, the brown coats on their muscular bodies appearing thick and sleek under the midday sun. Their horns were much lighter, massive, and arcing from their heads like fence posts bent into a circle. The rams failed to detect our approach from above, allowing us to sneak within a distance of perhaps half a city block from the nearest sheep.

For some time we watched them in silence. I can still recall their white nose patches and the pale fur on their rumps, the grinding of their molars as they chewed their cud, and the dark, cloven hooves at the end of their outstretched front legs. Beyond the rams the landscape peeled away in an emerald mosaic of timber and an endless chain of barren mountain peaks melding into an ageless blue sky. The wildness of the space and the strength of life that seemed to radiate from the lounging bighorns will remain with me until erased by death or dementia.

Despite their apparent virility, bighorns are fragile creatures. They snort at -30F temperatures, yet have less resistance to certain respiratory diseases than a newborn human. Perhaps more than any other species of hoofed mammal in North America, they need the care of thoughtful people to survive. After reading this book, I hope youll be amply motivated to do your part.

CHAPTER 1 Names and Faces

Names and Visual Description

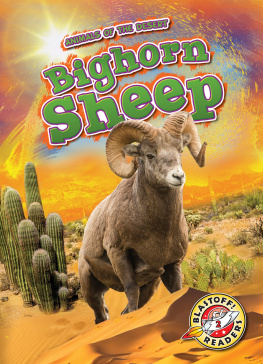

Bighorn sheep are creatures of the mountains and may also inhabit rough, badland regions of the plains. Their overall appearance is brown, varying from hues of rich chocolate to reddish or golden brown, depending on the region the animal inhabits and the time of year. Bighorns have stout, blocky bodies. Their tails are brown and stubby, and are only easily observed by the unaided eye from the rear at close range. The rump of the bighorn looks large, partly due to its highly developed muscles but also enhanced by its distinct coloration. In contrast to the brown body of the sheep, the rump appears cream-colored or pure white. Bighorns also have a pale patch of fur on the end of their nose, and varying levels of lighter fur on the inside of their legs and belly.

Although sheep in the truest sense of the word (bighorns can actually mate with domestic sheep in controlled conditions), observers expecting the long, woolly coat of the domestic sheep on a bighorn are mistaken. The bighorns fur is sleek and much shorter than that of a domestic sheep. In late winter their coats may fade considerably. Their fur becomes patchy when shedding in the spring and early summer, but for most of the year, their hair-coat looks sleek and well-groomed.

Both female and male bighorn sheep have horns. The horns of a mature male dwarf those of a female. The horns grow from the top of the head and curl out and backward. Exceptionally large males may have horns that spiral into a full circle when viewed from the side.

Bighorn sheep are named for the massive, spiraling horns found on males of the species.

American Indians inhabiting what is now the western portion of the United States utilized bighorn sheep for food and other purposes. Various tribes had different names for the sheep. The Blackfeet of northwestern Montana referred to the bighorn as big head. The Mandans of the Dakotas called the animal big horn, while the Crees of western Canada referred to the species as ugly reindeer. Early European trappers and explorers sometimes adopted the names of the native peoples for bighorn sheep, but naturalists were often confused about the specific identity of the animal.

Such was the case with members of the Lewis and Clark expedition. The captains were aware of the presence of bighorns before they encountered or killed one, based on verbal accounts from other explorers and a spoon Clark observed in a village of Teton Sioux fashioned from the horn of a bighorn sheep. On May 25, 1805, Clark killed a female bighorn in the bluffs along the Missouri River in eastern Montana. The captain described the animal as a female ibex or big horn animal, reflecting some of the confusion that surrounded the species in his day. Some American naturalists believed bighorns were a type of ibex, goatlike creatures that are native to central Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. Others believed them to be a strain of argali, wild sheep indigenous to eastern Asia. The confusion in the minds of Lewis and Clark is evident on their maps. In eastern Montana they named two separate watercourses Argalia Creek and Ibex Creek in the region where they first encountered bighorn sheep.

On Clarks eastward (return) journey down the Yellowstone River, he encountered a major tributary known by the Crow Indians as the Bighorn River, the name he adopted on his map which persists today. After decades of confusion in the nineteenth century regarding the rivers namesake animal, biologists successfully differentiated bighorn sheep from the argali and ibex of yonder continents and agreed upon the name bighorn sheep, which the animals carry today. The scientific name for bighorn sheep is Ovis canadensis .