Will Declair, Bao Dinh and Jerome Dumont

The Extra Hour

Powerful Productivity Techniques to Create More Time in Your Day

Contents

About the authors

(Will, Bao and Jerome)

Will is co-founder of clothing brand Loom, where he advocates for a textile industry that is more respectful of people and the environment. Prior to that, he co-founded Merci Alfred, a male generalist media outlet. In these two professions, what he prefers is choosing slightly obscure subjects to make (very) long articles.

Bao is an investor in venture capital. He invests in innovative early-stage companies and he supports their founders in their growth journey. He was previously Head of EMEA at HotelTonight, the hotel booking app acquired by Airbnb. He has traveled the world, and is a passionate cook who regularly invites Top Chef contestants to dinner at his place in the hope of scoring a few tips.

Jerome is an expert in user experience. He helps give a second life to objects by improving the experience of Back Market customers, an online platform dedicated to refurbished tech devices. He previously co-founded One More Thing Studio, a French mobile app development agency. He went to his first Burning Man Festival when he was 23 and has backpacked his way around the world. Jerome now organizes Opal, a free annual festival in France, and in his spare time plays guitar, rides a motor-bike and enjoys hanging around the more underground parts of Paris (literally).

If the pages of this book have helped you in any way, wed be delighted to hear from you at hey@extrahourbook.com. You can also find us on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter by searching for xhbook. We can also meet you and your colleagues in person: check out http://extrahourbook.com/conf.

For all those who type with one finger, and for those they drive crazy.

If youre interested in helping your coworkers or employees win back an extra hour every day, visit www.extrahourbook.com/enterprise or write to us at hey@extrahourbook.com for discounted bulk corporate orders and we will point you in the right direction!

Throughout the book, weve cited a bunch of very helpful tools. Now, productivity tools are evolving faster than the print rate of this book. If you cant find some of the tools we mention in this book, its probably because they have been replaced by more effective tools or have changed names. But we wont let you down, we are keeping an up-to-date list of tools at www.extrahourbook.com/tools.

Before we get started

LIFE IS SHORT

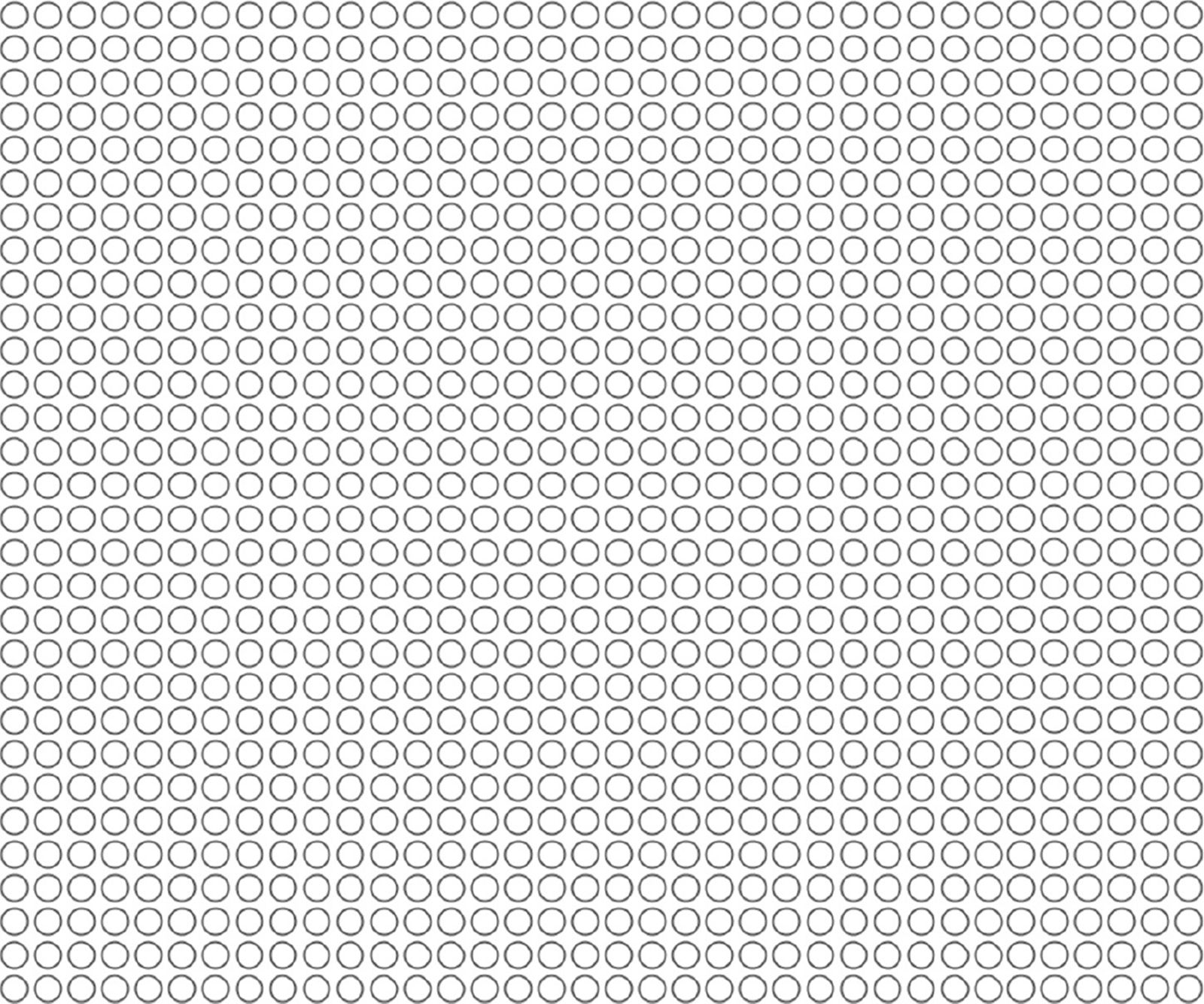

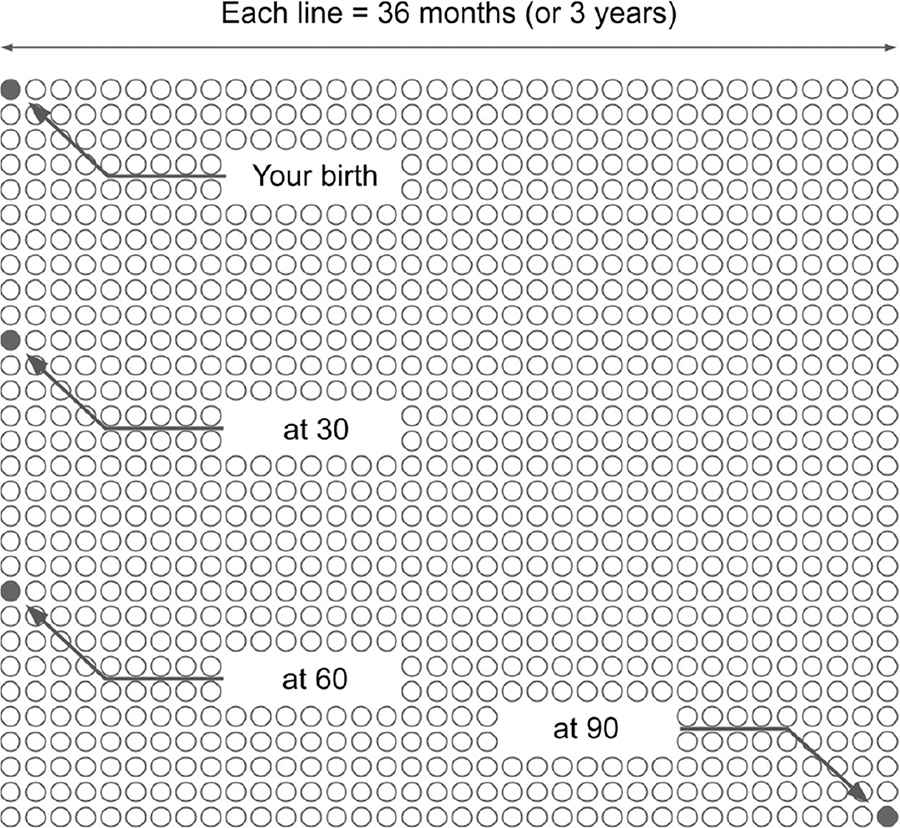

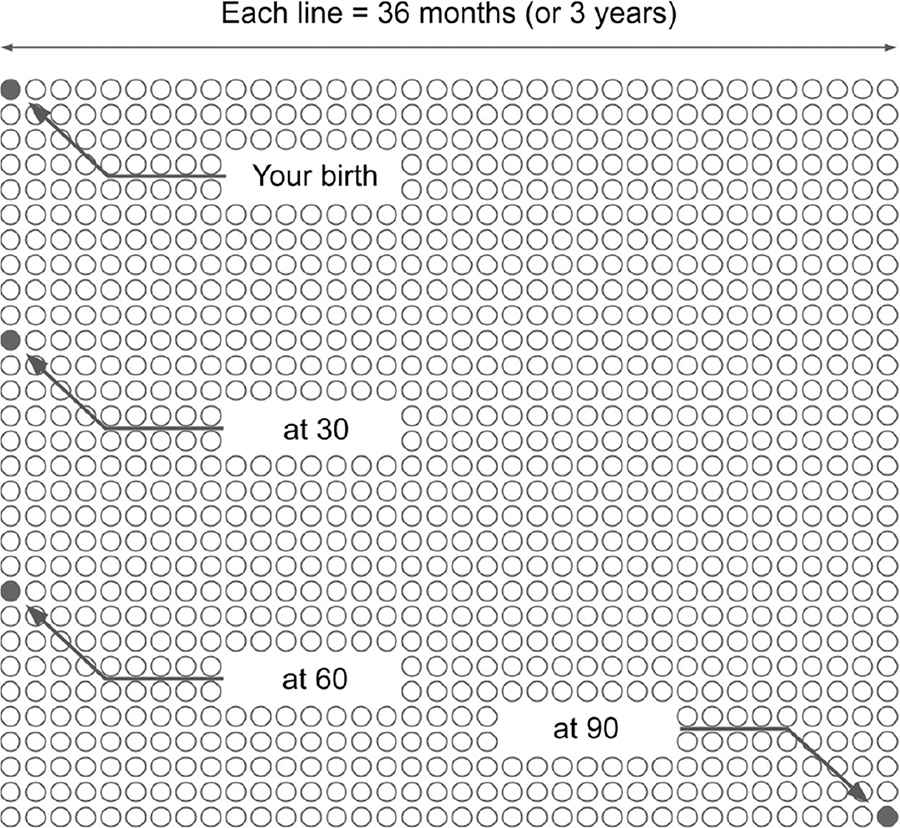

First up, a diagram, or rather a series of circles.

Each circle represents a month of your life.

For most, its hard to think of life as anything but an infinite series of months, each one spilling into the next. But here they all are: the months of your life, mapped out one by one. If youre 30, 60 or 90 years old, heres exactly where you stand on the diagram.

The above infographic by Tim Urban, the author behind the fantastic WaitButWhy blog demonstrates one thing: that life is a finite resource, and far too short to waste.

In this context, productivity is not the end in itself, but a means to a better overall existence. By spending as little time as possible on uninspiring, tedious tasks, we can spend more on what really makes us happy.

In other words, mastering productivity can help us live more fully. For you, that could mean:

> Heading off on an adventure somewhere youve always wanted to go.

> Enjoying long, meaningful conversations with friends over dinner.

> Coming home early in the evenings to spend time with your kids.

> Working on the projects that truly inspire you.

THE PROGRESS PARADOX WHY ARE WE WORKING MORE?

Three centuries ago, youd need to work for about six hours in order to pay for the quantity of candles required to see you through a reading of this book. Today, thanks to rising revenue and technological advances that have dramatically lowered the price of lightbulbs, you now only need to work half a second to get the same amount of light.

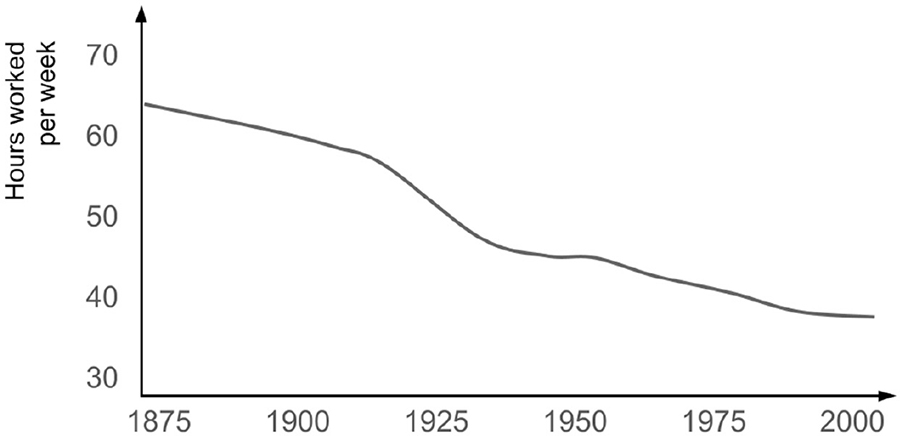

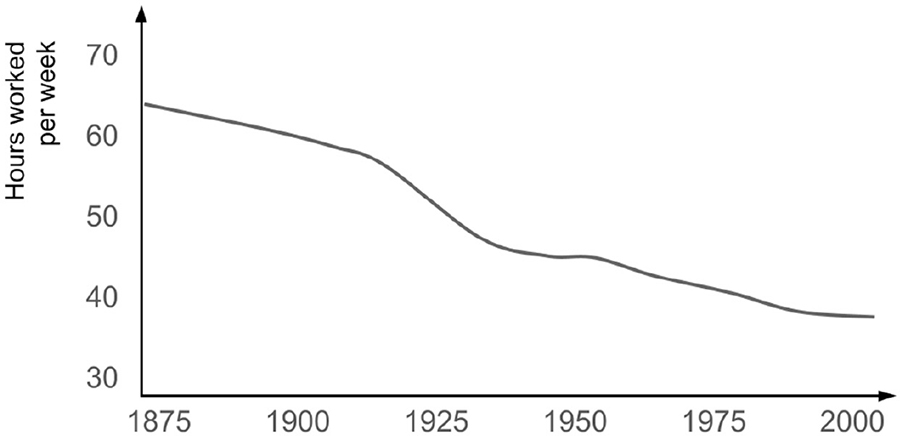

Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, output efficiency has risen considerably across most economic sectors. As a result, the number of hours worked per person has dropped significantly since then particularly among blue-collar workers.

The average working week of a North American/Western European blue-collar worker

In 1930, the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that with continuing advances in productivity, the twenty-first century would give rise to a 15-hour working week for all.

And yet this never happened. In fact, in recent years, progress in productivity has pretty much come to a halt.

The Third Industrial Revolution sees rapid growth in the IT and communications sectors. But following an initial spike in productivity, growth slowed to such an extent that between 2010 and 2016, productivity in North America and Western Europe increased by just 0.5 per cent per year. As far back as 1987, Nobel Prize-winning economist Robert Solow observed that you can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics, and this still holds true.

Where economists once imagined a steady decrease in working hours, the average working week for a full-time employee in the US has remained virtually unchanged since 2001 at just over 47 hours, compared with 42.6 in 2003.

These days, a laid-back lunch break is out of the question, and our workers are habitually underwater. Our friends work late into evenings and weekends, and the term burnout has become a standard part of our vocabulary. White-collar is the new blue-collar.

The introduction of machines successfully reduced the working week for blue-collar workers, but new technologies have not had the same benefits for their colleagues in the boardroom. Why?

Its a reasonable question. Whereas previous generations had little more than pens and paper to facilitate tasks, we now possess an impressive array of digital tools whose sole purpose is to make our jobs and lives easier, from streamlining tasks to full-on automating them.

One answer is that modern approaches to work actually make us less efficient. We waste too much time in pointless meetings, are endlessly interrupted in open-plan office spaces, and rely so heavily on digital technology that our smartphones, tablets and computers are constantly competing for our attention. Add in the constant stream of emails and text messages that endlessly disrupt our concentration, and it seems pretty clear that although we spend a lot of time at work, we dont actually get a whole lot of work done.

Our point here is that new technology should be used to liberate us from work, rather than tie us to it. We need to flip the roles in our relationship with digital technology and make it work for us, not the other way around. We should learn to harness the pressure we experience at work to motivate us, get organized, concentrate better, and work faster. By leaving the drudgery to digital technology, we can focus on the most creative and interesting aspects of our work and of our lives.

Next page

The average working week of a North American/Western European blue-collar worker

The average working week of a North American/Western European blue-collar worker