ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this book have appeared previously elsewhere: much of the "From Our Kitchen To Your Table" and a few other stray bits of business appeared in The New Yorker, under the title, "Don't Eat Before Reading This". The "Mission to Tokyo" section appeared first in Food Arts, and readers of my short story for Canongate Press's Rover's Return collection will see that the fictional protagonist in my contribution, "Chef's Night Out" had a humiliating experience on a busy broiler station much like my own. I'd also like to thank Joel Rose, to whom I owe everything... Karen Rinaldi and Panio Gianopoulous at Bloomsbury USA. Jamie Byng, David Remnick, the evil Stone Brothers (Rob and Web), Tracy Westmoreland, Jose de Meireilles and Philippe Lajaunie, Steven Tempel, Michael Batterberry, Kim Witherspoon, Sylvie Rabineau, David Fiore, Scott Bryan, and my ass-kicking crew at Les Halles: Franck, Eddy, Isidoro, Carlos, Omar, Angel, Bautista and Janine.

Cooks Rule.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: I have changed the names of some of the individuals and some of the restaurants that are a part of my story.

To Nancy

CONTENTS

APPETIZER

A Note from the Chef

FIRST COURSE

Food Is Good

Food Is Sex

Food Is Pain

Inside the CIA

The Return of Mal Carne

SECOND COURSE

Who Cooks?

From Our Kitchen to Your Table

How to Cook Like the Pros

Owner's Syndrome and Other Medical Anomalies

Bigfoot

I Make My Bones

The Happy Time

Chef of the Future!

Apocalypse Now

The Wilderness Years

What I Know About Meat

Pino Noir: Tuscan Interlude

DESSERT

A Day in the Life

Sous-Chef

The Level of Discourse

Other Bodies

Adam Real-Last-Name-Unknown

Department of Human Resources

COFFEE AND A CIGARETTE

The Life of Bryan

Mission to Tokyo

So You Want to Be a Chef? A Commencement Address

Kitchen's Closed

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

APPETIZER

A NOTE FROM THE CHEF

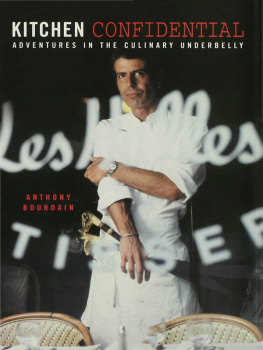

DON'T GET ME WRONG: I love the restaurant business. Hell, I'm still in the restaurant business--a lifetime, classically trained chef who, an hour from now, will probably be roasting bones for demi-glace and butchering beef tenderloins in a cellar prep kitchen on lower Park Avenue.

I'm not spilling my guts about everything I've seen, learned and done in my long and checkered career as dishwasher, prep drone, fry cook, grillardin, saucier, sous-chef and chef because I'm angry at the business, or because I want to horrify the dining public. I'd still like to be a chef, too, when this thing comes out, as this life is the only life I really know. If I need a favor at four o'clock in the morning, whether it's a quick loan, a shoulder to cry on, a sleeping pill, bail money, or just someone to pick me up in a car in a bad neighborhood in the driving rain, I'm definitely not calling up a fellow writer. I'm calling my sous-chef, or a former sous-chef, or my saucier, someone I work with or have worked with over the last twenty-plus years.

No, I want to tell you about the dark recesses of the restaurant underbelly--a subculture whose centuries-old militaristic hierarchy and ethos of "rum, buggery and the lash" make for a mix of unwavering order and nerve-shattering chaos--because I find it all quite comfortable, like a nice warm bath. I can move around easily in this life. I speak the language. In the small, incestuous community of chefs and cooks in New York City, I know the people, and in my kitchen, I know how to behave (as opposed to in real life, where I'm on shakier ground). I want the professionals who read this to enjoy it for what it is: a straight look at a life many of us have lived and breathed for most of our days and nights to the exclusion of "normal" social interaction. Never having had a Friday or Saturday night off, always working holidays, being busiest when the rest of the world is just getting out of work, makes for a sometimes peculiar world-view, which I hope my fellow chefs and cooks will recognize. The restaurant lifers who read this may or may not like what I'm doing. But they'll know I'm not lying.

I want the readers to get a glimpse of the true joys of making really good food at a professional level. I'd like them to understand what it feels like to attain the child's dream of running one's own pirate crew--what it feels like, looks like and smells like in the clatter and hiss of a big city restaurant kitchen. And I'd like to convey, as best I can, the strange delights of the language, patois and death's-head sense of humor found on the front lines. I'd like civilians who read this to get a sense, at least, that this life, in spite of everything, can be fun.

As for me, I have always liked to think of myself as the Chuck Wepner of cooking. Chuck was a journeyman "contender", referred to as the "Bayonne Bleeder" back in the Ali-Frazier era. He could always be counted on to last a few solid rounds without going down, giving as good as he got. I admired his resilience, his steadiness, his ability to get it together, to take a beating like a man.

So, it's not Superchef talking to you here. Sure, I graduated CIA, knocked around Europe, worked some famous two-star joints in the city--damn good ones, too. I'm not some embittered hash-slinger out to slag off my more successful peers (though I will when the opportunity presents itself). I'm usually the guy they call in to some high-profile operation when the first chef turns out to be a psychopath, or a mean, megalomaniacal drunk. This book is about street-level cooking and its practitioners. Line cooks are the heroes. I've been hustling a nicely paid living out of this life for a long time--most of it in the heart of Manhattan, the 'bigs'--so I know a few things. I've still got a few moves left in me.

Of course, there's every possibility this book could finish me in the business. There will be horror stories. Heavy drinking, drugs, screwing in the dry-goods area, unappetizing revelations about bad food-handling and unsavory industry-wide practices. Talking about why you probably shouldn't order fish on a Monday, why those who favor well-done get the scrapings from the bottom of the barrel, and why seafood frittata is not a wise brunch selection won't make me any more popular with potential future employers. My naked contempt for vegetarians, sauce-on-siders, the "lactose-intolerant" and the cooking of the Ewok-like Emeril Lagasse is not going to get me my own show on the Food Network. I don't think I'll be going on ski weekends with Andre Soltner anytime soon or getting a back rub from that hunky Bobby Flay. Eric Ripert won't be calling me for ideas on tomorrow's fish special. But I'm simply not going to deceive anybody about the life as I've seen it.

It's all here: the good, the bad and the ugly. The interested reader might, on the one hand, find out how to make professional-looking and tasting plates with a few handy tools--and on the other hand, decide never to order the moules marinieres again. Tant pis, man.

For me, the cooking life has been a long love affair, with moments both sublime and ridiculous. But like a love affair, looking back you remember the happy times best--the things that drew you in, attracted you in the first place, the things that kept you coming back for more. I hope I can give the reader a taste of those things and those times. I've never regretted the unexpected left turn that dropped me in the restaurant business. And I've long believed that good food, good eating is all about risk. Whether we're talking about unpasteurized Stilton, raw oysters or working for organized crime "associates", food, for me, has always been an adventure.