To Ariane and Jacques

CONTENTS

Guide

For their large and small contributions to the making of this book, wed like to thank:

Paul Ackerina

Olivia Mack Anderson

Beth Aretsky

Eddie Barrera

Ruby Basdeo

Anna Billingskog

Danny Bowien

Andreana Busia

Angelo Busia

Ariane Busia-Bourdain

Ottavia Busia-Bourdain

Sonya Cheuse

Helen Cho

Suet Yee Chong

John Cogan

Chris Collins

Milo Collins

Neko Collins

Ariane Daguin

Lizzie Roller Dilworth

Angela Dimayuga

Lolis Elie

Chris Faulkner

Josh Ferrell

Bobby Fisher

Dahlia Galler

Giacomo Gambineri

Ashley Garland

Theo Granof

Victoria Granof

Daniel Halpern

Jon Heindemause

Anya Hoffman

Ruby Hoffman-Werle

Tema Hoffman-Werle

Nicholas Krasznai

Alison Tozzi Liu

Caleb Liu

Micah Liu

Tony Liu

Dave Luebker

Melissa Lukach

Peter Meehan

Rachel Meyers

Emily Miller

Flavio Moledda

Joshua Monesson

Max Monesson

Nathan Myhrvold

Patty Nusser

Nick Olivieri

Sophia Pappas

Miriam Parker

Jason Perez

Buster Quint

Doug Quint

Jacques Quizon

Marcus Quizon

Myra Quizon

Rommel Giant Quizon

Bridget Read

Eric Ripert

Matt Roady

Mark Rosati

Allison Saltzman

Cathy Sheary

Ralph Steadman

Lydia Tenaglia

Ashley Tucker

Theo van den Boogaard

Kaitlyn DuRoss Walker

Jonathan Werle

Maisie Wilhelm

Kimberly Witherspoon

Monika Woods

John Woolever

Patricia Woolever

All happy families are alike...

Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Tolstoy clearly never spent any time with my happy family.

My eight-year-old daughter, Ariane, does a terrific imitation of my wife threatening to choke a taxi driver. Its something shes seen often enough to get dead rightmy wifes Italian accent, her anger, her exasperation as the driver takes yet another wrong turn on the way to my daughters school, and finally the kicker: Im going to keel you with my bare-a hands!

It has been many months, maybe years, since anyone has seen my wife out of her regular attire of rash guard and spats. Shes a martial artist, a purple belt in Brazilian jiujitsu, and she trains full-time, seven days a week. Most of her efforts are spent practicing horrifying new ways to quickly, forcibly manipulate opponents feet, ankles, and knees in such ways as to permanently damage their tendons and ligaments.

I travel the world for a living. On any given day, Im as likely to be found in a longhouse in Sarawak, Borneo; in a cafe in Marseille; or in an airport transit lounge in Doha as I am to be found at home. My daughter is used to seeing her fathers face on TV and on the sides of city buses, accustomed to seeing him approached by strangersand is decidedly unimpressed.

Her best friend, Jacques (pronouned Jax), from whom she has been inseparable most of her life, is Filipino, part of an extended family who easily spends as much time in our home as anywhere else. English, Italian, and Tagalog are heard interchangeably. My daughter is increasingly fluent in Italian. I am not.

What is it that normal people do?

What makes a normal happy family?

How do they behave? What do they eat at home? How do they live their lives?

I had little clue how to answer these questions for most of my working life, as Id been living it on the margins. I didnt know any normal people. From age seventeen on, normal people had been my customers. They were abstractions, literally shadowy silhouettes in the dining rooms of wherever it was I was working at the time. I looked at them through the perspective of the lifelong professional cook and chefwhich is to say, as someone who did not have a family life, who knew and associated only with fellow restaurant professionals, who worked while normal people played, and who played while normal people slept.

To the extent that I knew or understood normal peoples behaviors, it was to anticipate their immediate desires: Would they be ordering the chicken or the salmon?

I usually saw them only at their worst: hungry, drunk, horny, ill tempered, celebrating good fortune or taking out the bad on their servers.

What they did at home, what it might be like to wake up late on a Sunday morning, make pancakes for a child, watch cartoons, throw a ball around a backyardthese were things I only knew from movies.

The human heart wasand remainsa mystery to me. But Im learning. I have to.

I became a father at fifty years of age. Thats late, I know. But for me, it was just right. At no point previously had I been old enough, settled enough, or mature enough for this, the biggest and most important of jobs: the love and care of another human being.

From the second I saw my daughters head corkscrewing out of the womb, I began making some major changes in my life. I was no longer the star of my own movieor any movie. From that point on, it was all about the girl. Like most people who write books or appear on television, who think that anyone would or should care about their story, I am a monster of self-regard. Fatherhood has been an enormous relief, as I am now genetically, instinctually compelled to care more about someone other than myself. I like being a father. No, I love being a father. Everything about it.

Im sure my wife has a different view on this, but if I could go back to the diaper-changing, wake-up-in-the-middle-of-the-night-to-soothe-crying-baby phase of fatherhood? Id be overjoyed.

I recognize that I am, in some ways, overenthusiastic about this late-in-life move into responsible parenting. And that I have a tendency to try to make up for lost time. Since so many of my happiest memories of childhoodsummer vacations at the Jersey shore, off-season Montauk, trips to Franceare associated with the tastes and smells of the things I ate, I feel uncontrollable urges to smother the people I love with food. Ive become the sort of passive-aggressive yenta or Italian grandmother stereotype from films whos always urging people, Eat! Eat! and sulking inconsolably when they dont.

This pathology is further complicated by my time as a professional. I have developed work habits that, over three decades, imprinted on me the need to be organized, to have a plan, to rotate stock, to label prepared foodstuffs, and to keep a clean work area.

So on top of my desire to make up for lost time, and my psychoIna Gartenlike need to feed the people around me, I am obsessive-compulsive in my work habits and anally retentive in ways that youd find ideal in a professional brunch cook, but probably disturbing in a husband or parent.

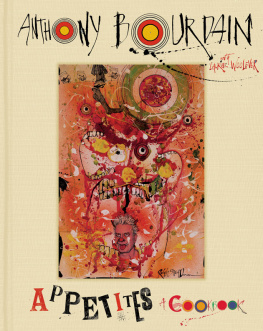

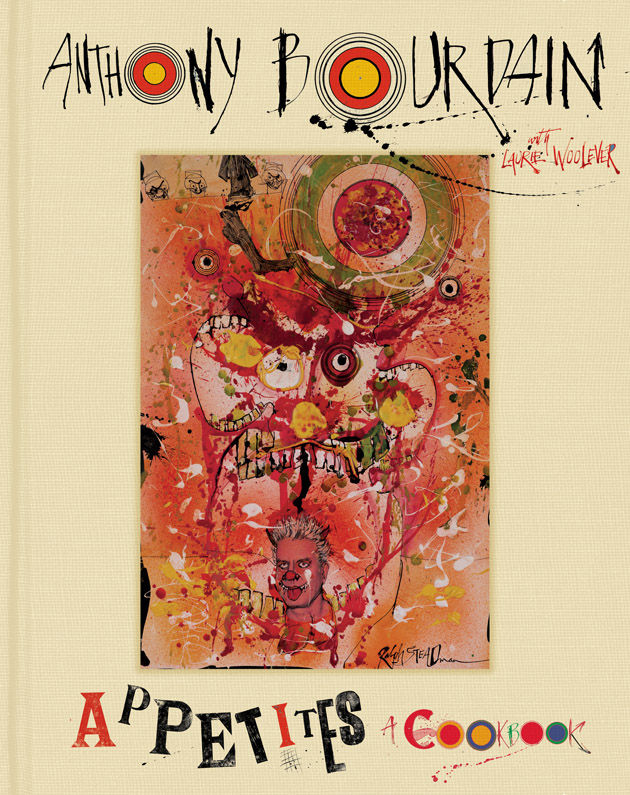

Thats our family. And this is our family cookbook.

These are the dishes I like to eat and that I like to feed my family and friends. They are the recipes that work, meaning theyve been developed over time and have been informed by repetition and longand often painfulexperience.

As happens in the restaurant business, I will, from time to time, make small incremental sacrifices in quality for the often more important matter of serviceability. While it is a laudable ambition to prepare the best risotto in the world, that doesnt mean shit if your guests are sitting around with their stomachs growling, getting progressively drunker, while you dick around in the kitchen, interminably stirring rice.