This Is One Way to Dance

Valerie Boyd and John Griswold, series editors

SERIES ADVISORY BOARD

Dan Gunn

Pam Houston

Phillip Lopate

Dinty W. Moore

Lia Purpura

Patricia Smith

Ned Stuckey-French

This Is One Way to Dance

ESSAYS

Sejal Shah

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2020 by Sejal Shah

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk New

Set in Arno Pro

Printed and bound by Sheridan Books

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for

permanence and durability of the Committee on

Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the

Council on Library Resources.

Excerpt from The Site of Memory

copyright 2018 by Toni Morrison. Reprinted by

permission of ICM Partners.

Most University of Georgia Press titles are

available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed in the United States of America

20 21 22 23 24 P 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shah, Sejal, 1972 author.

Title: This is one way to dance : essays / Sejal Shah.

Description: Athens : The University of Georgia Press, 2020. | Series: Crux:

the Georgia series in literary nonfiction | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020001681 | ISBN 9780820357232 (paperback) |

ISBN 9780820357249 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH : Gujarati AmericansBiography. | Children of immigrants

United StatesBiography. | East Indian American womenBiography. |

Racially mixed peopleUnited StatesBiography. |

East Indian AmericansEthnic identity.

Classification: LCC PS 3619. H 3483 Z 46 2020 | DDC 8/8/.603 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020001681

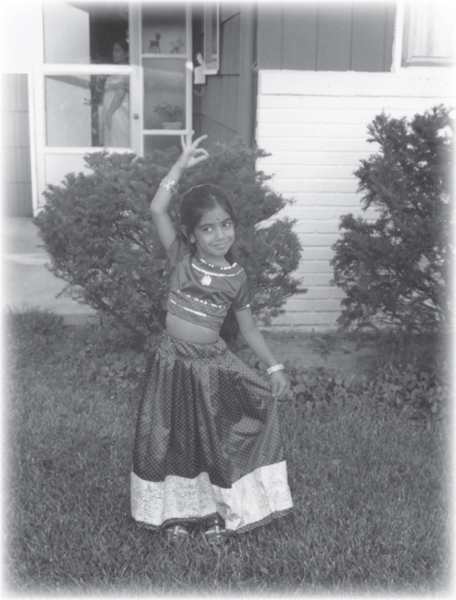

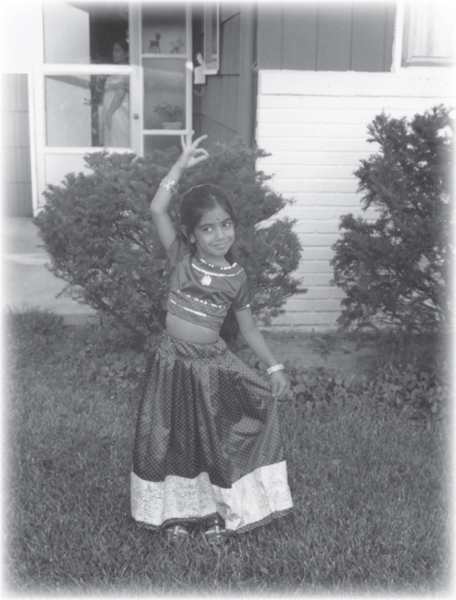

Title page image: photo of the author at age four,

with her grandmother, Indumati N. Shah,

who is looking through the glass door.

For R

In memory of

LeeAnne Smith White

and my grandmother,

Indumati Natverlal Shah

Contents

Introduction

There was an intermission; it was that long. I saw Gandhi in the movie theater and still remember my indignation that the director chose a white actor to play the most famous Indian. Later I learned that Ben Kingsley is half-Gujarati; his birth name is Krishna. I was ten, growing up outside Rochester, New York, a part of western New York thats both racially and socioeconomically hypersegregated. I have always thought about race and representation. I wanted to see something of the life I knew in a book, on a screen. I felt that way in the long-ago movie theater as a child; I felt that way when I was in my twenties and in graduate school. Sometimes I still feel that way. I began writing to make a point of view, people, and entire cultural references I never saw reflected in what I read or watched.

This book is in part about growing up Indian outside of India, in non-Indian places; about the formation of ethnic identity in small cities and towns in the United States, away from urban centers. Kakali Bhattacharya writes, We [South Asian Americans] are sometimes either invisible or hyper-visible, coopted by model minority discourses or caricatured in characters like Apu in The Simpsons. Our invisibility stems from being racialized as non-white and non-Black, so that even in antiracist discourses we disappear because we are neither. I wanted to explore the feelings of both invisibility (of not even counting in the racial landscape) and hypervisibility (of always being other, a stranger, from somewhere else, the person expected to serve on the institutional diversity committee) for Asian Americans in this country. How do you make yourself visible and legible to yourself in a world that often does not see you or only sees race? How do you take up space? These essays meditate on objects and place. How do you move in a body often viewed as other? How do you claim the I, the person dancing, the person leading the dance?

Since my book spans two decades, and the United States and I have both changed in that time, Ive noted the year(s) each was written at the end of the essay. In general, I ordered my essays chronologically by the present in each piece, though several move around in time. I wrote the earliest, Skin, in 1999. Rereading and rethinking these essays has been a kind of excavation. I lived in picturesque Western Massachusetts then, a beautiful college town, and was frustrated with the lack of any visible South Asian or Asian American culture. I never felt as aware of being Indian and brown as during some of the time I lived in Amherst while in graduate school. During those years, the weddings of the kids of family friends, who were my friends from growing up, gave me a place to be unselfconsciously Indian, to dance, to connect.

These essays wrestle with identity, language, movement, family, place, and race. I am the daughter of Gujarati parents born in India and British East Africa. My life existed both as part of the diasporic culture in which I was raised (home, parents, community) and where I lived and grew up (western New York). I wrote these essays across twenty years, beginning in Massachusetts in the late 1990s and continuing through moves to New York City and Iowa, for fellowships and jobs, back to my hometown of Rochester. These essays address the passing of time, the loss of a dear friend, the childhood pool that no longer exists, my ambivalence about wedding jewelry, the brother-in-law I will never meet. I wrote about my older brothers wedding and ten years later, watching Monsoon Wedding. I wrote about 9/11. I wrote about what it feels like to lose a language you grew up with and to be able to express this loss only in another language.

I once called this book Things People Say after my essay Things People Said because I found myself so often incredulous and then furious over things people had said to me. It took time to unpack and unwind my visceral responses and what those words communicated to me. I could feel the kick underneath, the teeth. Microaggressions. Writing was a way to have my sayto pick up those words like a piece of glass and turn it over in the sun and consider the sharp edges or blunted corners. Telling the story, rendering a scene, making a list, allowed me to puzzle, to make a mosaic of these different parts. I believed there was something to learn and understand in my responses. However, I changed the title after I realized I didnt want to frame my writing only in response to other peoples words. Why give them more space? Ill take that space.

Of my parents, brother, and myself, I am the only one of us who still lives in the country in which she was born. I have never visited the countries of my parents birth with them, nor have I seen Uganda and Kenya at all. All I have is here. Weddings conjured those countries and culturestheater, spectacle, acting, gathering. I think thats partly why they had a pull on me. For nearly all of the time I attended those weddings I was single. Weddings are about cultures and family and dancing. For me, they were not as much about getting married but about being young, about that time in my life, about having a place and a reason to dance. This is not a book about weddings, even though I write about them. This is a book with weddings as part of the landscape, and in many of those years I was in graduate school and a professor, I was a wedding-goer, hopping from job to fellowship to job, state to state, trying to make a life for myself. My friends and family did not elope. Weddings were family and community events. They belonged to more than just the people getting married.

Next page