About the Book

An offbeat journey to the heart and soul of an alluring but elusive land.

Shortly after the 2005 London bombings, travel writer and film-maker Tahir Shah was thrown into a Pakistani prison on suspicion of spying for Al-Qaeda. What sustained him during his terrifying, weeks-long ordeal were the stories his father told him as a child in Morocco

Inspired by this, on his return to his adopted homeland, he embarked on an adventure worthy of the mythical Arabian Nights and went in search of the stories and storytellers that have nourished this ancient, vibrant country for centuries.

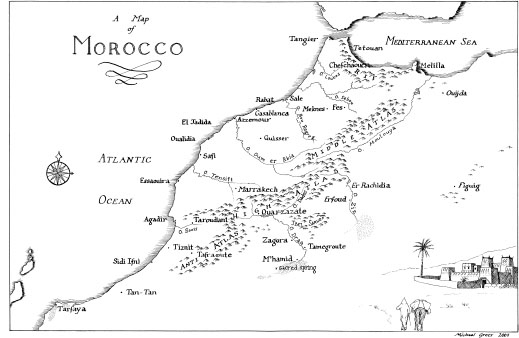

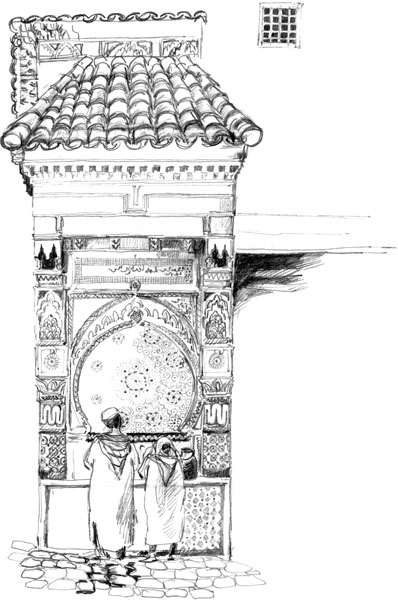

Wandering through the medinas of Fez and Marrakech, criss-crossing the Sahara sands and tasting the hospitality of ordinary Moroccans, he collects a treasury of traditional stories recounted by a vivid and eccentric cast of characters: from master masons who work only at night to Sufi wise men who write for soap operas and Tuareg guides addicted to reality TV.

Himself a link in the chain of scholars and teachers who have passed such tales down from father to son, mother to daughter, Tahir Shah reveals a world and a way of thinking that most visitors to Morocco barely know exist.

Contents

This book is for my aunt Amina Shah, Queen of the Storytellers.

Here we are, all of us: in a dream-caravan.

A caravan, but a dream a dream, but a caravan.

And we know which are the dreams.

Therein lies the hope.

Sheikh Bahaudin

Nasrudin was sent by the king to find the most foolish man in the land and bring him to the palace as court jester. The mulla travelled to each town and village in turn, but could not find a man stupid enough for the job. Finally, he returned alone.

Have you located the greatest idiot in our kingdom? asked the monarch.

Yes, replied Nasrudin, but he is too busy looking for fools to take the job.

The World of Nasrudin by Idries Shah

ONE

Be in the world, but not of the world.

Arab proverb

THE TORTURE ROOM was ready for use. There were harnesses for hanging the prisoners upside-down, rows of sharp-edged batons, and smelling salts, used syringes filled with dark liquids and worn leather straps, tourniquets, clamps, pliers, and equipment for smashing the feet. On the floor there was a central drain, and on the walls and every surface, dried blood plenty of it. I was manacled, hands pushed high up my back, stripped almost naked, with a military-issue blindfold tight over my face. I had been in the torture chamber every night for a week, interrogated hour after hour on why I had come to Pakistan.

All I could do was tell the truth: that I was travelling through en route from India to Afghanistan, where I was planning to make a documentary about the lost treasure of the Mughals. My film crew and I had been arrested on a residential street and taken to the secret torture installation known by the jailers as The Farm.

I tried to explain to the military interrogator that we were innocent of any crime. But for the military police of Pakistans North West Frontier Province, a British citizen with a Muslim name, coming overland from an enemy state India set off all the alarms.

Through nights of blindfolded interrogation, with the screams of other prisoners forming an ever-present backdrop to life in limbo, I answered the same questions again and again: What was the real purpose of your journey? What do you know of Al-Qaeda bases across the border in Afghanistan? And, even: Why are you married to an Indian? It was only after the first week that the blindfolds were removed and, as my eyes adjusted to the blaring interrogation lamps, I caught my first burnt-out glimpse of the torture room.

The interrogations took place only at night, although day and night were much the same at The Farm. The strip-light high on the ceiling of my cell was never turned off. I would crouch there, waiting for the sound of keys and for the thud of feet pacing over stone. That meant they were coming for me again. I would brace myself, say a prayer and try to clear my mind. A clear mind is a calm one.

The keys would jingle once more and the bars to my cell would swing open just enough for a hand to reach through and grab me.

First the blindfold and then the manacles.

Shut out the light, and your other senses compensate. I could hear the muffled screeches of a prisoner being tortured in the parallel block and taste on my tongue the dust out in the fields.

Most of the time, I squatted in my cell, learning to be alone. Get locked up in solitary in a foreign land, with the threat of immediate execution hanging over you, a blade dangling from a thread , and you try to pass the time by forgetting where you are.

First I read the graffiti on the walls. Then I read it again, and again, until I was half-mad. Pens and paper were forbidden, but previous inmates had used their ingenuity. They had scrawled slogans in their own blood and excrement. I found myself desperate to make sense of others madness. Then I knelt on the cement floor and slowed my breathing, even though I was so scared words could not describe the fear.

Real terror is a crippling experience. You sweat so much that your skin goes all wrinkly like when youve been in the bath all afternoon. And then the scent of your sweat changes. It smells like cat pee, no doubt from the adrenalin. However hard you wash, it wont come off. It smothers you, as your muscles become frozen with acid and your mind paralysed by despair.

The only hope of staying sane was to think of my life, the life that had become separated from me, and to imagine that I was stepping into it again into the dream that, until so recently, had been my reality.

The white walls of my cell were a kind of silver screen on which I projected the Paradise I longed to return to. The love for that home and all within washed out the white walls, the blood-graffiti and the stink of fear. And the more I feared, the more I forced myself to think of my adopted Moroccan home, Dar Khalifa, the Caliphs House.

There were courtyards brimming with fountains and birdsong, and gardens in which Timur and Ariane, my little son and daughter, played with their tortoises and their kites. There was bright summer sunlight, and fruit trees, and the voice of my wife, Rachana, calling the children in to lunch. And there were lemon-coloured butterflies, scarlet red hibiscus flowers, blazing bougainvillea and the hum of bumblebees dancing through the honeysuckle.

Hour after hour I would watch my memories screened across the blank walls. I would be blinded by the colours, and glimpse in sharp detail the lives we had created for ourselves on the edge of Casablanca. With my future now in the balance, all I could do was pray. Pray that I might be reunited with that life, a melodious routine of innocence, interleaved with gentle calamity.

As the days and nights in solitary passed, I moved through the labyrinth of my memories. I set myself the task of finding every memory, every fragment of recollection.

They began with my childhood, and with the first moment I ever set foot on Moroccan soil.

Next page