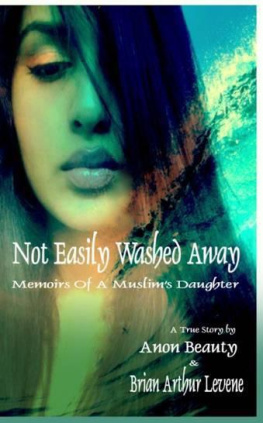

This is a true storythough some identifying details have been changed for reasons of safetyand is in no way a denigration of Islam in general. It is a personal account of my own life experiences, and deals with the way that Islam was practiced within my own community, as I witnessed it growing up.

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

From my childhoodthe images sketchy and opaque, a splash of color here and there among darknessI remember one thing clearly: my street. East Street, in Bermford, the north of England. Two rows of identical, brick-built Victorian houses and a shady park at the north end like leafy branches atop a blood-red trunk. I saw the gnarled trees as fanged monsters among whose knotted, bestial shadows our childhood games darted.

I flitteddaydreaming, pigtailed, hand-me-down mary janes rubbing the long spine of the cracked sidewalkfrom house to house. Doors were always left open, and there was no fear of being robbed. I could wander down to my friend Aminas place whenever I felt like it. I was welcome to stay for as long as I wanted. If I was out for more than three or four hours, someone would come looking for memy mother or one of my brothers. But it was still a kind of freedom for a little child.

Id be offered a drink of Pakistani teawater boiled with tea leaves, hot milk, heaps of sugar, and sometimes cardamomand something to eat. It was chocolate digestives or Rich Tea biscuits one day and curry or chapattis the next. Hours later I found my way home, skipping past window after window blooming yellow into the dark soil of night.

It was the 1980s. We were Pakistani. We were British. We were East Street.

My mother made chapattis with wholemeal flour. She kneaded it with water to form dough, then took a fistsized blob, rolled it out into a flat circle on a chapatti iron, and cooked it until dark spots appeared on its surface. She made parathas, rolling out the dough into pancakes and placing them on a long-handled tava pan. As she tossed them in the oil, each one puffed up like a doughy balloon.

We ate with our hands, using the chapatti or paratha to scoop. Mum made samosas with spiced minced meat, or potato and peas. She made pakoras out of slices of onion and fresh chili peppers, coated in a gram flour batter and dropped into sizzling-hot oil. I watched them cook below the surface, watching for them to rise, golden brown, like fried chicken nuggets.

Across the street lived an Armenian family, a mother and her one sonone of the few families on our street who werent of Pakistani Muslim origin. The Armenian mother tried to communicate with Mum, but her English was very limited. Mum told us to call her Auntie as a traditional sign of respect, but Dad didnt agree. He refused to show respect to anyone except other Pakistani Muslimsnot even the Indian Muslims who lived around the corner on Jenna Street.

Armenian Auntie brought us Armenian food and Mum took Pakistani delicacies to them. Mostly, we were given vegetarian hotpotsaubergines, potatoes, and carrots stewed in a salty, peppery sauce. Before we were allowed to eat, Mum went through the food with a fork, checking for any suspect meat. If there wasnt any, we were free to tuck in.

When the weather was good, Armenian Auntie dragged a pinewood chair into her front yard. She sat there with her son, soaking up the sun and peeling potatoes. We talked in passing, across the green picket fence, but we never went inside. She understood she wasnt welcome in our home, and she didnt invite us into her house, either. Thankfully, she couldnt have known the lack of welcome was because my father hated white people.

A few doors down lived a second Armenian familymother, father, and daughter. They went to mass at an Orthodox Christian church and growled at everyone else on the street. Several other houses were filled with a rotating cast of rentersblack students from the Congo, Cameroon, and Algeria.

Everyone else on our street was a Pakistani Muslim. The adults dressed as they would have in a village in Pakistan: women and men wore shalwar kamiz, a loose, matching smock top and trousers. The womens were more colorful, while the men had baggy trousers, in more sober, masculine colors, like browns, grays, and whites. Dad was always dressed in a white shalwar kamiz with a topi, a traditional Punjabi skullcap, on his head.

Most of the men changed when they went to work. They seemed to shrug on a Western skin when they left our street and entered the city as taxi drivers, policemen, engineers, and salespeople. None of the women of my parents generation worked, but some of the younger ones took jobs as secretaries or helpers in shops, at least until they married. They always kept themselves properly covered and showed appropriate modesty.

Four doors down lived my Great-Uncle Kramat and Great-Auntie Sakina. They were our surrogate grandparents, for our real ones were back in the village in Pakistan. I didnt entirely like going to their house. I was scared of Uncle Kramat, who could be quite fierce with his long, white beard and bushy eyebrows joining together in the middle. He and Auntie Sakina gossiped about my parents while they drank tea and watched television.

Uncle Kramat and Auntie Sakina had three grown childrentwo married sons, Ahmed and Saghir, and a married daughter, Kumar, all of whom lived with Uncle Kramat and Auntie Sakina. That wasnt unusual on our street.

None of Uncle Kramat and Auntie Sakinas children had any children. The neighbors gossiped darkly that this was a punishment from Allah. Uncle Kramat was

Good luck or bad luck was often attributed to someones moral or spiritual behavior. Uncle Kramats lack of piety was understood as the reason for his childrens infertility; yet the gossipers ignored the fact that Ahmed, Saghir, and Kumar had married their first cousins. In any case, it was agreed the entire family ought to accept Allahs will and stop such nonsense as in-vitro fertilization.

Islam is first and foremost submission to Allahs will. Indeed, a believer is often spoken of as the slave of God. There is a common misconception that the primary meaning of Islam is peace, but that is true only in that a believer finds peace by submitting to Allahs will.

My best friend was Amina. She had unruly dark hair that fell to her shoulders in a wild tangle. Neither of us thought it was very pretty, but she had to live with it. Aminas sister, Ruhama, with her thick, wavy hair, was considered by far the prettier of the two. Both girls were paler-skinned than my sisters and me.

Shes so pretty! people in the street and at school would remark of Ruhama. Shes got such lovely hair, and such pale skin! When I heard this, I presumed that dark skin was less beautiful.

Aminas household seemed more relaxed than mine. Her parents didnt pray regularly, and apart from her Quran lessons Amina was rarely made to read the holy book. Neither she nor Ruhama ever had to wear a