Contents

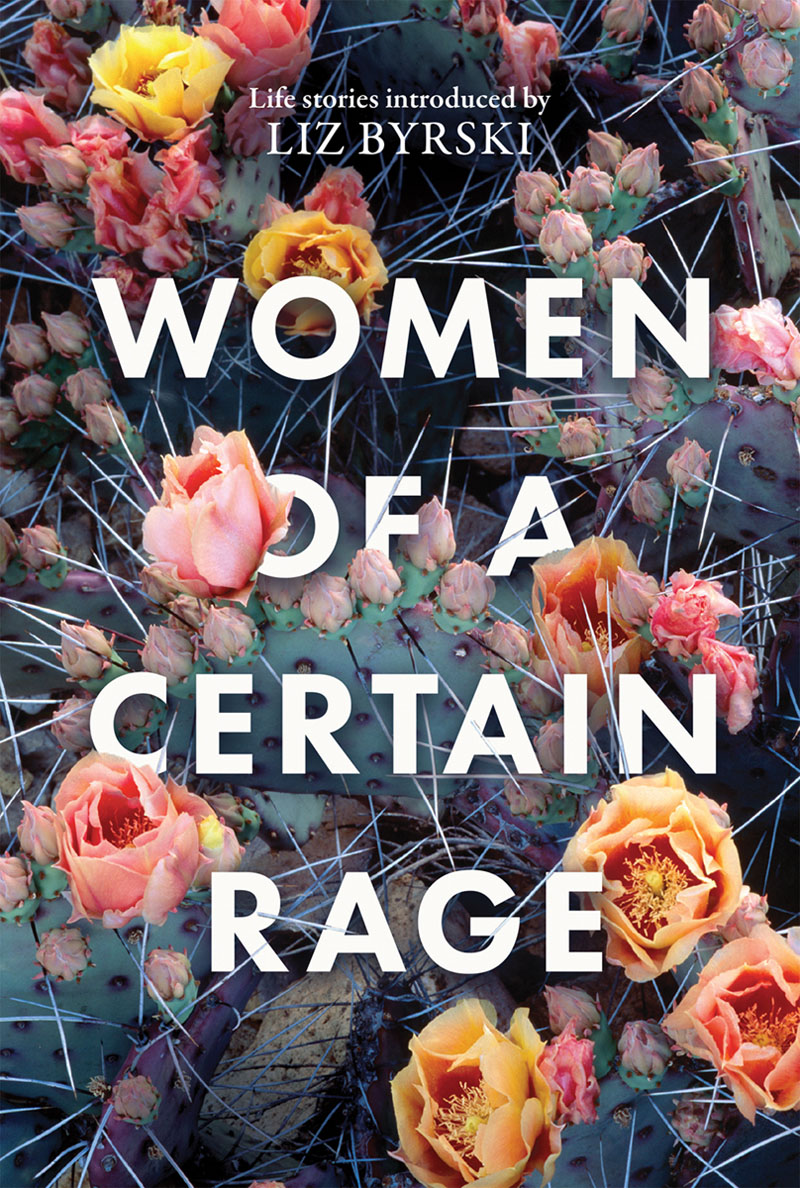

Introduction Liz Byrski

Let us go forth with fear and courage and rage to save the world.

Grace Paley

Welcome to this collection of womens personal stories and essays about their rage. This is a book that would not have been published in my mothers youth, and probably not in my own, before the emergence of second-wave feminism in the late 1960s. Indeed, there are still many people and organisations that believe that womens anger is abhorrent. Public demonstrations of rage by women are still frequently portrayed as shocking by commentators, politicians and many media outlets: think Serena Williams outburst of rage at the umpire in the 2018 US Open. Williams was vilified by commentators, columnists and widespread audiences of viewers who have, for decades, allowed male players to get away with similar, and often far worse, displays of rage, dismissing them with humour or with a shrug and a rueful smile: think John McEnroe, among others.

My favourite example of a woman expressing her rage not only in public but in the Australian Parliament is that of then prime minister Julia Gillards 2012 attack on then opposition leader Tony Abbott. Gillards powerful, articulate and finely tuned rage at Abbotts misogyny left Parliament and the country gasping. Today, that speech is remembered around the world, and to date it has had over 3.3 million views on YouTube. Even so, womens anger still attracts widespread and often vicious condemnation, while manifestations of mens anger so often pass without comment. Speaking out is powerful, but for many women it is still a terrifying prospect because retribution can take many forms.

#MeToo had already become an international voice for women on the impact of misogyny and sexism when publisher Georgia Richter and I sent out invitations to possible contributors to this book. #MeToo is a powerful recognition of the cruel and ruthless abuse of women, and it appears to be the platform from which many offenders will eventually be brought to justice. Sharing their rage has helped women to feel believed, understood and supported, as well as able to recognise themselves as part of a narrative that is bigger than any individual.

Georgia and I explained in our invitation that we would like to explore some of the other issues that can inspire and ignite womens rage. We had no idea what to expect, and received a number of immediate responses from some women telling us that they did not feel not angry enough to contribute. That, of course, was fine and indicated that some of the women on our list had come to terms with those things that raised their ire, or at least they had no need or desire to express it on paper.

What we learned, as we waited for submissions from those who were energised by the prospect of expressing their rage in this way, was that many of the contributors often writers by vocation were truly struggling with the subject matter.

It transpires that it is one thing to feel rage, and quite another to articulate it, not least because writing it down can lead to experiencing the rage all over again. As the submissions arrived, Georgia and I devoured them with growing excitement at the diversity of the topics, and the power and eloquence of the writing. We compared notes on the way in which each story affected us. We shed tears, we laughed out loud, and we learned so much from these very personal and often deeply moving stories.

The women who have contributed to this book come from widely differing backgrounds, races, beliefs and identities. They range in age from their twenties to their eighties, and they write with passion, courage, humour and with, and of, their rage. There are writers here poets, novelists, essayists, playwrights and journalists as well as women in the public service, academics, teachers, medical professionals, activists and professionals from film and television. They are Australian mothers, daughters, granddaughters and wives. They write with empathy, wisdom and despair about their rage, and with power about their attempts to turn their anger into action, and about learning how to live with it.

This book begins and ends with two proudly self-styled cranky women. In her piece A Door, Opening, a cranky Victoria Midwinter Pitt suggests that Anger is a state of opposition. It is not merely intellectual, or philosophical. Its personal. It is the direct, visceral, spiritual experience of being at odds with something.

Hers is a definition that encapsulates the stories in this book, speaking to the range of powerful, moving, sometimes heartbreaking and often funny pieces.

Goldie Goldbloom, in To the Max, writes of the blatantly cruel neglect of an elderly relative, while in Seen and Not Heard, Meg McKinlay tells of the way in which a character in a childhood book became her model of anger and continues to inspire her writing.

There are fathers here: emotionally absent ones, and those whose presence casts a frightening shadow. And there is laughter too: Julienne van Loon takes the wisdom of Seneca, her most admired philosopher, and tests its value against the realities of life as a working mother. And Carrie Cox wonders resignedly why rage never runs on time.

Womens determination is apparent in Olivia Muscats To Scream or Not to Scream, in which her rage is not against her blindness but at the patronising and diminishing responses to it. And in Vicarious Trauma, Carly Findlay expresses her horror at the level of oversharing and ableism by parents and others as they expose the lives of their disabled babies and children on social and public media.

Many pieces rage at the things we cannot control, and then offer up responses as to how we can. In her essay The Thief, Nandi Chinna writes of the single event that dramatically changed her life, and how she has learned to live with its shadow. Professor Fiona Stanley (on the Australian governments response to the Uluru Statement), Rene Pettitt-Schipp (on immigration detention) and Margo Kingston (on climate change) offer models of activism as a means of responding to government positions that feel morally untenable. Jane Underwood tries and fails and tries again to be zen about social injustice when it comes very close to home.

All this and so much more is contained here in the stories of twenty women who took up the challenge of revealing and interrogating the meaning of rage. As Fiona Stanley asks in her opening statement: is rage pointless (and maybe harmful to our own health) or are there ways of raging productively?

Reading these pieces is one way of finding out.

I began this introduction by noting the emergence of second-wave feminism, which I remember as a hugely positive time of my life. It was a time in which I learned about politics and about women, their anger and their power to create change. It was a time of extraordinary hope and inspiration, in which the friendship of women, and their ability to stand and work fearlessly together, was obvious to us as activists. Many real societal improvements were achieved during this time; awareness and understanding and support around the issues that mattered to us grew. There were improvements and increasing opportunities in areas of medicine, the law, education, training and the workplace. And greater attention was drawn to violence against women at home, in the workplace and in public places. I recall a strong sense of togetherness and purpose through the 1970s, along with enormous satisfaction when the work eventually delivered results: breast cancer screening, abortion law reform, the slow dissolution of discrimination against women in employment, in government and union careers, in the law and the police force and so much more.

Next page