Simon May - How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging

Here you can read online Simon May - How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Pan Macmillan, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

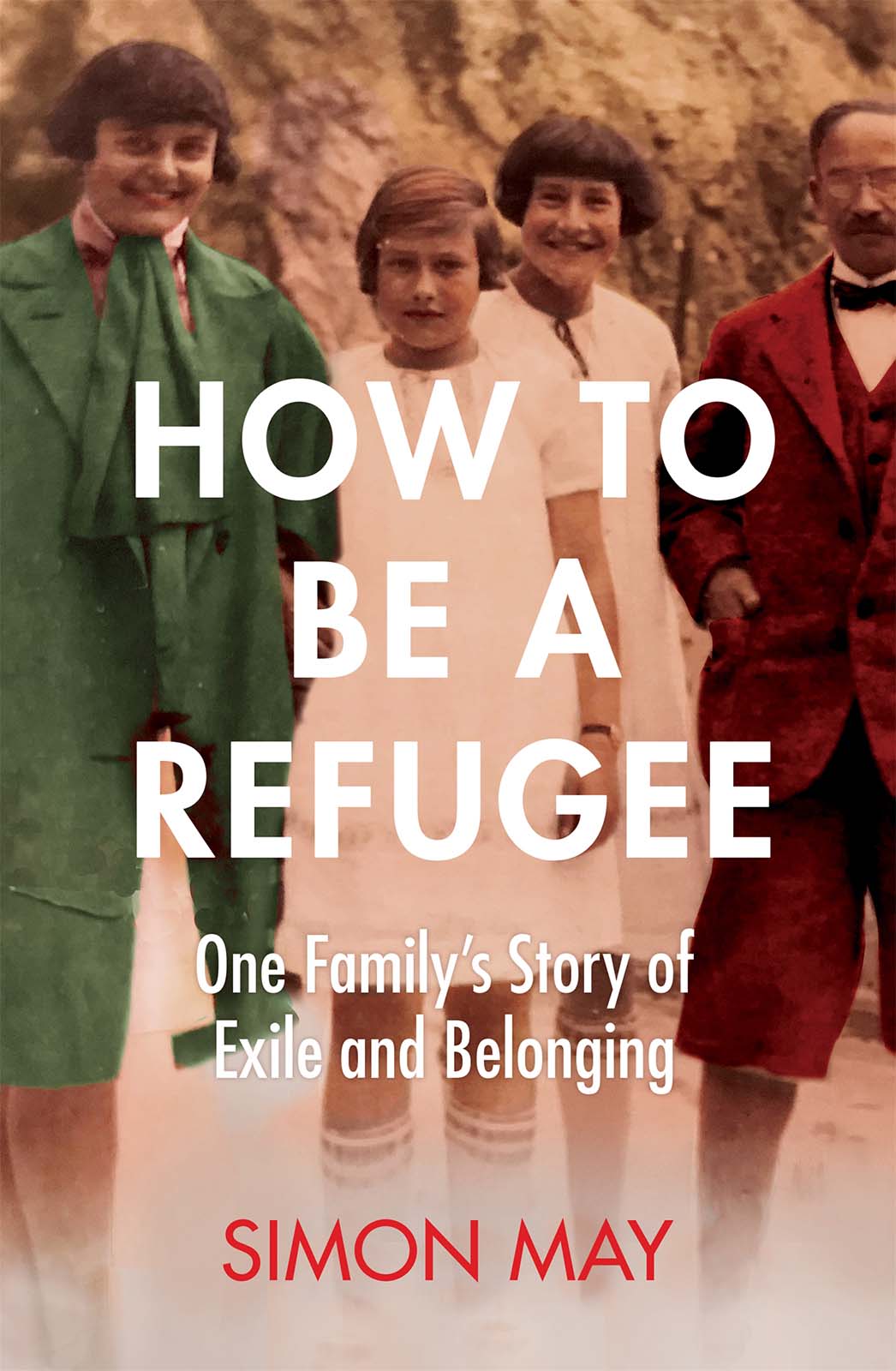

- Book:How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging

- Author:

- Publisher:Pan Macmillan

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Simon May: author's other books

Who wrote How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

With inexpressible gratitude to Marianne, Ursel,

and Ilse my mother and my two aunts; to my grandfather

Ernst and great-uncle Theo, who died long before I was born,

but whose lives have inspired and challenged me since childhood;

and to my beloved father Walter and my grandmother Emmy,

both of whom I knew only briefly.

CONTENTS

PART I

A BERLIN IDYLL: 19101933

PART II

THREE SISTERS, THREE DESTINIES: 19331945

PART III

NEWLY CREATED WORLDS: 19451990

PART IV

THE PAST CANNOT BE RESTITUTED: 1990

[E]verything must be earned, not only the present and future, but the past as well... and this probably entails the hardest work of all.

Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena

That was your father you found. Youve been carrying your fathers bones all this time.

Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon

Relationship to the author is shown in brackets

ERNST LIEDTKE , 18751933 (maternal grandfather): born Christburg, then in West Prussia. Lawyer; husband of Emmy; father of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne. Converted from Judaism to Protestantism. Died in Berlin after being expelled from his profession in April 1933 under the Nazi ban on non-Aryan lawyers.

EMMY LIEDTKE , 18901965 (maternal grandmother): born Emmy Fahsel; wife of Ernst and mother of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne. Lived in Germany all her life. Converted to Catholicism.

THEODOR LIEDTKE , 18851943 (maternal great-uncle): brother of Ernst Liedtke; uncle of Ilse, Ursel, and Marianne; salesman at Tietz department store in Berlin; deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1942, and from there to Auschwitz.

HELMUT FAHSEL , 18911983 (maternal great-uncle): Catholic priest and philosopher. Left Germany in 1934 for Switzerland on a tip-off from Franz von Papen, Hitlers deputy chancellor. Apart from a brief spell in Germany after the war, spent the rest of his life in Switzerland.

ILSE LIEDTKE , 19101986 (older maternal aunt): photographer who spent the war in Berlin. Lover of Harald Bhmelt, composer and Nazi Party member. Except for a few years in Kiel from 1948, she lived in Berlin all her life. Converted to Catholicism.

URSULA (URSEL), COUNTESS VON PLETTENBERG , 19121995 (younger maternal aunt): born Ursula Liedtke. Actor who became a Catholic; secured Aryan status in 1941 with the help of Hans Hinkel, a senior official in Hitlers regime; married Franziskus, Count von Plettenberg in 1943; fled to the Netherlands in 1944; returned to Germany soon after the war and lived there for the rest of her life.

MARIANNE MAY , 19142013 (mother): born Marianne Liedtke. Violinist, stage name Maria Lidka; emigrated to London in 1934; married Walter May in 1955. Converted to Catholicism.

FRANZISKUS, COUNT VON PLETTENBERG , 19141968 (maternal uncle by marriage): married Ursel in 1943; deserted the German army in the Netherlands in 1944 and went into hiding with Ursel.

WALTER MAY , 19051963 (father): born in Cologne. A banker and then a brush manufacturer; emigrated to London in 1937. His first wife Hilde May was also a cousin; his second wife was Marianne Liedtke.

EDWARD MAY , 19031968 (paternal uncle): born in Cologne. Doctor, amateur cellist, and master chef; emigrated to London in 1934.

KLAUS MELTZER , 19432017 (putative cousin): claimed to be a grandson of my great-uncle Theodor Liedtke. Son of Ellen Liedtke and Nazi Staffelkapitn Walter Meltzer. Lived in Cologne. Photographer; painter; educationalist; founded a community centre for Turkish women.

ELLEN LIEDTKE , 19191971: putative daughter of Theodor Liedtke, whom Ernst, Emmy, Marianne, Ursel, and Ilse all believed to be a childless bachelor.

The most familiar fate of Jews living in Hitlers Germany is either emigration or deportation to concentration camps. But there was another, rarer, and today much less well known side to Jewish life at that time: denial of your origin to the point where you manage to erase almost all consciousness of it. You refuse to believe that you are Jewish. In reaction to a long history of racial and religious persecution, and out of intense love for German culture, you repudiate your birthright.

This feat of repudiation, epitomized by my mother, her sisters, and her parents, did not originate with Hitlers rise to power. The ground for it was prepared long before, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when some Jews, such as Rahel Varnhagen the great woman of letters, whose extraordinary intellect and sensibility were admired by Goethe, Schiller, and Wilhelm von Humboldt, among other luminaries of her time came to regard their heritage as a curse that poisoned their whole existence and debarred them from full belonging in the world of German culture, to which they were so fervently devoted.

But in my mothers family such repudiation of origins was pushed to an extreme, becoming an ethnic purging of the inner world a profound alchemy of the soul. Nor did it cease with Hitlers defeat. Though my mother had fled to London from Nazi Germany and I was born well after the war into a vastly more tolerant era, I was forbidden to think of myself not only as Jewish but now also as German or British.

I have attempted to tell the story of the extraordinary German-Jewish world from which my family came as well as of my own quest to carve a path to both its heritages principally through the remarkable lives of three sisters: my mother and my two aunts. Their very different ways of grappling with what they experienced as a lethal origin included conversion to Catholicism, marriage into the German aristocracy, securing Aryan non-Jewish status with high-ranking help from inside Hitlers regime, and engagement to a card-carrying Nazi under whose protection survival in wartime Berlin was possible. But we also meet other figures with a similar heritage, such as my maternal great-uncle, who became a Catholic priest and translator of St Thomas Aquinas; and the love child of a Jewish woman and a passionate Nazi, who, so far unknown to us, claimed me and my family as his sole surviving relatives.

To recount these contortions of ethnic and cultural concealment is categorically not to criticize them. Who are we who have never experienced racial hatred in its vehement forms, let alone in the form of state-sanctioned persecution, to criticize anyones strategy to survive and flourish in such conditions? Who are we who have lived free lives where our particular heritages have been accepted and sometimes even admired, to cast judgement on ancestors who were forced to find ever more ingenious ways of appearing harmless to the majority and to themselves? Their choices are only my business because to be born into this strange tributary of the Jewish experience was to be commanded to construct an identity out of everything that I was not. Following the early death of my father, also a German-Jewish refugee, I was raised a Catholic and mandated, on pain of betraying my mother and her parents, to live as a refugee in the country of my birth. In effect, I was instructed never to arrive anywhere: to be a hereditary refugee.

The urgent questions that this raised for me questions of identity and belonging that seem to be everywhere around us today are these: Are we not all in some way exiles in an era that is shedding its past at unprecedented speed? Can the worlds we have lost be restituted, even if minimally, along with their rich networks of meaning, without fruitless, and possibly self-destructive, efforts to set the clock back? Or is all restitution a pipe dream: are lost worlds necessarily the unattainable territory of ghosts who powerfully inspire our lives from a great distance, but with whom we can never live or speak again? Either way, how many generations can it take for a refugee family to feel at ease in their adopted country, no longer pining for a place from which they were once uprooted? And at a time when identity is becoming a choice rather than just a given, will it get easier or harder to be a refugee?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging»

Look at similar books to How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book How to Be a Refugee: One Familys Story of Exile and Belonging and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.