Copyright 2003 by the University of Washington Press

First paperback edition, 2013

Introduction to the paperback edition 2013 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Designed by Pamela Canell

16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

PO Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145, USA

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Atkins, Gary, 1949

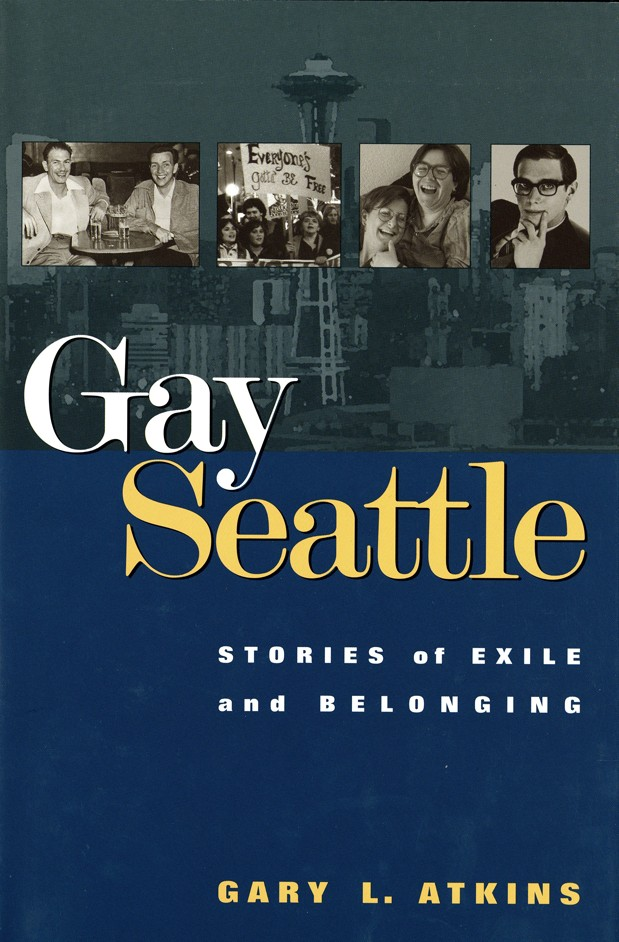

Gay seattle : stories of exile and belonging / Gary L. Atkins, with a new introduction by the author. First paperback edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-99282-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. GaysWashington (State)SeattleSocial conditions. 2. Gay rightsWashington (State)SeattleHistory. 3. Gay liberation movementWashington (State)SeattleHistory. 4. AIDS (Disease)Washington (State)SeattleHistory. I. Title.

HQ76.3.U52S433 2013 306.76609797772dc23 2013002232

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

ISBN-13: 978-0-295-80099-8 (electronic)

INTRODUCTION TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

When I first started work on Gay Seattle in the fall of 1992, I thought the project would be quick, maybe a year. As a narrative journalist, my passion is fusing stories about real individuals and their struggles into reflections about bigger political questions. In the case of Gay Seattle, that question was about how a group of citizens marginalized for decades journeyed from a life spent in closeted exile to having a public voicein other words reaching a sense of home. Naively, I figured historians and sociologists had already done their jobs and that an overview of important events and individuals would be readily available. I thought it would be easy enough to then plot other details of the sexual and gender outliers who had been living in a city that was simultaneously Midwestern in its outlook and raucous in its embrace of Alaskan-inspired natural riches.

Instead, the research and writing took almost ten years. I learned to look for needles buried in the haystacks of microfiche and microfilm in city, county, state, and federal archives. I read records of lobotomies performed at the states mental hospitals. I tracked key individuals who had disappeared from the Seattle gay scene and were living, as I was sometimes told, in the islands somewhere. For years I sent my students out with video cameras to record interviews with both old-timers and those young and brand new to the queer side of the Northwest.

I am happy that over the past decade since its publication, the book has been well received. It collected several awards, among them a Washington State Book Award for what was called the importance of its subject and the quality of its storytelling. It also received a good share of critical praise, from both journalists and academic historians. I have to admit, though, that while I was happy that the hardback edition would join other durable hardbacks on library shelves, I also wished it was, well, lighter and more mobilethe kind of book you could easily carry, bend, and mark up without feeling guilty. So I am very happy that the University of Washington Press has decided to issue a new paperback edition of the original, as well as to bring the book into the twenty-first century by digitizing it for all those whose libraries now reside on an e-reader, smart phone, or other book device.

This new edition is not intended to be a revision of the original work or an expansion to cover in great detail what has happened since. It is also not intended to fill what are still pressing needs in Seattles sexual historya book about the rich history of transgender Seattle, for example. Those tasks are better left to entirely new booksor entirely new types of media platforms for storytelling. However, in this introduction I do want to update a few key ways in which the saga of coming home has unfolded since the stories in Gay Seattle closed in the mid-1990s.

As I was writing this preface in November 2012, Washington state citizens were determining the fate of what was called Referendum 74. The vote was to decide whether all adults in the state should have an equal civil right to marry the person they love. The state legislature had approved the idea, but now the voters had their chance at approving or vetoing what the legislature had decided. Although six states and the District of Columbia had already legalized same-sex marriage, it had been courts or legislatures that made those decisions. Each time voters had a direct chance to decide, majorities rejected same-sex marriages.

In that respect, the situation in Washington State at the end of 2012 was similar to that encountered three decades earlier, when, in 1978, Seattle voters had to decide the outcome of Initiative 13. That anti-gay initiative would have repealed the city councils decision to add sexual orientation to the list of types of citizens who could not be discriminated against in housing or employment. Across the country, opponents of civil rights protections for gays and lesbians had successfully overturned every similar decision by a city council. (The story of how Seattle became one of the first cities to retain its protections, breaking the oppositions national campaign, is told in .)

A campaign about and a vote by a majority upon the rights of a minority is, of course, a peculiar idea, especially when that majority has been deeply trained by particular historical or cultural blinders to see possibilities only one wayin the case of Referendum 74, the possibility of what marriage meant. For me, having been raised as a Southerner during the civil rights days of the 1960s, the campaign brought to mind the movie The Help, which earlier in 2012 had won the Academy Award for Best Picture. The plot of The Help focused on a fictional white womens bridge club in the 1960s that was planning a Home Help Sanitation Initiative. That initiative would have insured that all white families employing African American maids and nannies provided them with outside toilets. That way, the black women could then be banned from soiling the inside bathrooms being used by the whites. The woman promoting the initiative, a character named Hilly, feared that allowing the black maids to use the inside toilets would infect white families with disease and threaten the whites identity as superior.

Her solution: separate but supposedly equal toilets. But, of course, they were not really equal if they were still outside instead of inside the home. That very notion of being outside or inside is what the stories in this book track.

As related in It was the cultural blinder that assumed the persons involved must be a Jack and a Jill, not a Jack and a Jack. One activist, who had taken on the name of Faygele benMiriam (his real name was John Singer), promptly filed for a marriage license with a friend, Paul Barwick. In what then became the basic message that would echo through four subsequent decades, until the 2012 referendum, the men told the journalists who showed up for the inevitable rejection of a license by the county clerk that they were simply two human beings who happen to be in love and want to get married.