ANCIENT WOODLAND

HISTORY, INDUSTRY AND CRAFTS

Ian D. Rotherham

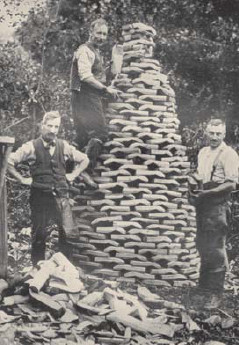

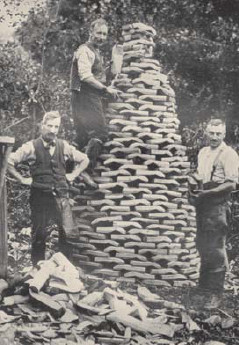

Clog-block makers in the woods were a common sight from the eighteenth century onwards. Beech or sycamore were preferred for their hardness but many clogs were made from alder. (A clog-maker in NorthWales assures me that alder was chosen because it was soft and easy to work, but that it produced poor-quality clogs.)

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

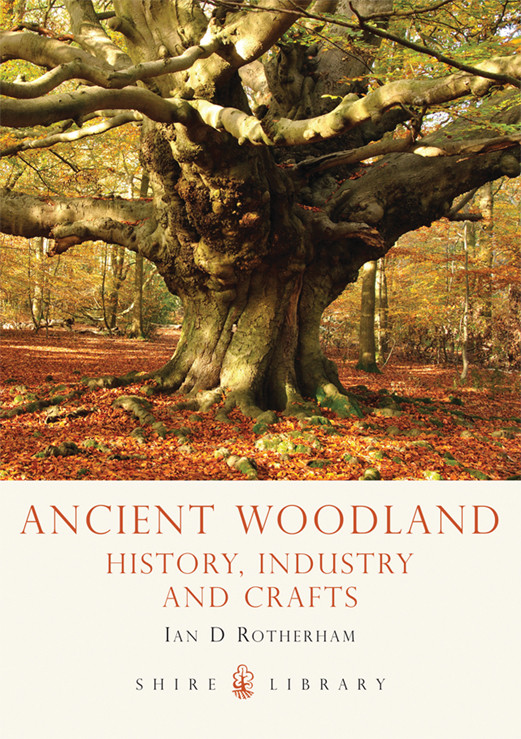

Old Oaks onWickham Common in Kent, after a painting by S. Johnson and published as a postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons (oilette, 1920s to 1930s).The typical ancient pollard oaks of a working common are shown.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

WHAT IS AN ANCIENT WOOD?

WOODS, PARKS AND FORESTS

WORKED AND WORKING TREES

WOODLAND CRAFTS AND OTHER INDUSTRIES

WOODLAND ARCHAEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY

THE FUTURE: RE-DISCOVERING THE OLD CRAFTS

FURTHER READING

PLACES TO VISIT

INTRODUCTION

CONTRARY TO POPULAR BELIEF, Britains ancient woodlands are not wildwoods, or even remnants of wildwood. These truly cultural landscapes mix nature and human history, woven as uniquely rich tapestries of ecology and history. The story of the woods is there to be read if you have time, enthusiasm, and this book, which will take you from prehistory to the present day. The types of landscape, geology and climate, and even differences in industries and manufacturing history, have placed varying demands on woods to create strong regional distinctiveness. This has led to woods developing local character depending on the ecological type of woodland present originally, and then the varying uses to which it has been put over the centuries by craftsmen as diverse as the bodgers of the Chilterns and the tan-bark merchants of Cumbria.

Ancient hazel coppice, Lathkill Dale, Derbyshire.

There is widespread popular and academic interest in woodlands and their history and archaeology. Yet there is little literature that addresses these topics. Based on over twenty years of field and archival research, this book is unique in bringing together this information in a single accessible volume. With the publication in 2008 of the Woodland Heritage Manual there is now an accepted approach to the subject and interest in this long-neglected field is growing rapidly. The subject covers a wide range of topics, from extractive industries in woods, to the crafts based on extraction or harvesting of woodland products, and their processing. For centuries, these crafts were at the centre of British society, fundamental in the creation and protection of many of the landscapes we value today. However, as technologies changed and markets for products evolved, many of the woodland traditions and crafts were abandoned and forgotten, with just a few of the old crafts surviving to the present day. The footprints of lost craftsmen are indelibly etched into every ancient wood across the country; the only problem is in recognising and understanding the evidence. Even the wild woodland flowers and their distribution reflects the one-time uses of the sites, as do the formerly worked trees. Humps and bumps of soil are now archaeology. These woods contain uniquely rich diversities of features ancient and modern, from wood banks and ditches, to trackways, charcoal hearths, Q-pits, bell-pits, quarries and building platforms.

Ancient small-leaved lime, Whitwell Wood.

Reading these landscapes can take you back over four thousand years of history, even in urban ancient woodland. It can help us reconstruct the local landscape and its unique history. Not only is the evidence physically imprinted into the environment, but woods and wooded landscapes are also recorded in place names, settlement names, and field names such as Wood End, Wood Lane, Hagg Side, Hollins End, Endowood, Woodseats, Woodthorpe, Willowgarth, Owlerton and the like. Woodseats, for example, would be the cottages deep in the wood, and Clayroyd a woodland clearing with clayey soil. From early medieval times, woods were themselves named: Park Spring or Parkwood Springs (the park coppice wood), West Haigh Wood (the enclosed wood), Newfield Spring (the coppice wood by the new field), and many others. Family names also reflect the wooded past with Underwood, Woodward, Hurst, Frith, Wood, Turner, Collier, Greenwood, Tanner, Forester, Warren, Warrender, Stubbs and Parker being just a few examples.

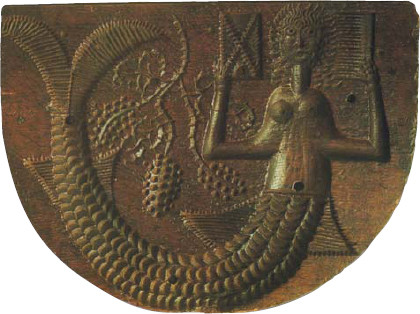

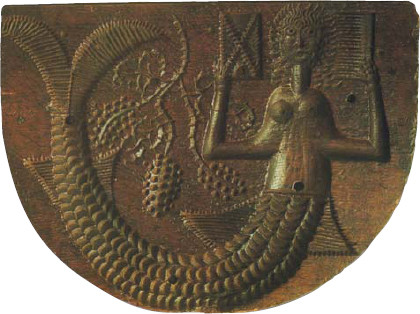

Wood and timber were of great importance before plastic was invented. Here is a bread oven door from the 1600s, carved from oak.

The most familiar woodland flower and often an indicator of an old woodland site the native bluebell.

To walk through an ancient wood is to tread in the footsteps of the ghosts of those who once lived and worked in the medieval and early industrial countryside. The ancient wood is frequently part of a greater landscape of medieval park, of common or heath, of chase or forest. This book helps unravel the mysteries of the past now locked away in soils and trees. Identifying ancient coppice stools, stubbed boundary trees, or veteran pollards from a long-forgotten deer park or old hedgerow will bring an understanding of how the countryside looked and functioned in times past. These wonderful ancient landscapes come to life as the history of woodland workers and others over a thousand years or more is unfurled.

In many cases, there are strong regional differences and identities that persist in the woods of today. These may relate to particular industries and intensive uses, such as the Derbyshire and south Yorkshire charcoal makers who worked so hard to fuel the Industrial Revolution. With practice, these regional identities can be recognised and identified. Fragments of ancient woods are to be discovered as broad hedgerows along old sunken lanes and trackways in urban and countryside areas, often still with veteran trees and woodland indicator plants. They are found close to rivers and streams, in green spaces such as golf courses, and even on modern housing estates it is just a matter of looking.

Finally, the study of woods and woodlands lends itself to the local group and the local enthusiast, and almost everyone will have one or more suitable sites that are accessible. Many woods remain hardly known and little understood. Studying the local area can make a real and lasting contribution to knowledge and understanding of these most iconic and important, but often misunderstood, landscapes. Step inside a local wood and, with practice, one can read its landscape and its ecology like the pages of a book. Ancient woodlands are remarkable repositories of the history and archaeology of the woodland and its management; also of the people and communities who have lived in that landscape, perhaps as long ago as prehistoric times. Oddly, they have until recently been largely overlooked by archaeologists. This is not always the case when there is obvious major heritage on a site, such as some of the Chiltern beech woods. Here the massive prehistoric fortifications are well documented. Yet in the heart of the city of Sheffield, in Ecclesall Woods, an entire hilltop enclosure, a Romano-British field system, a medieval deer-park boundary, and hundreds of charcoal hearths, lay undiscovered until about ten years ago.

Next page