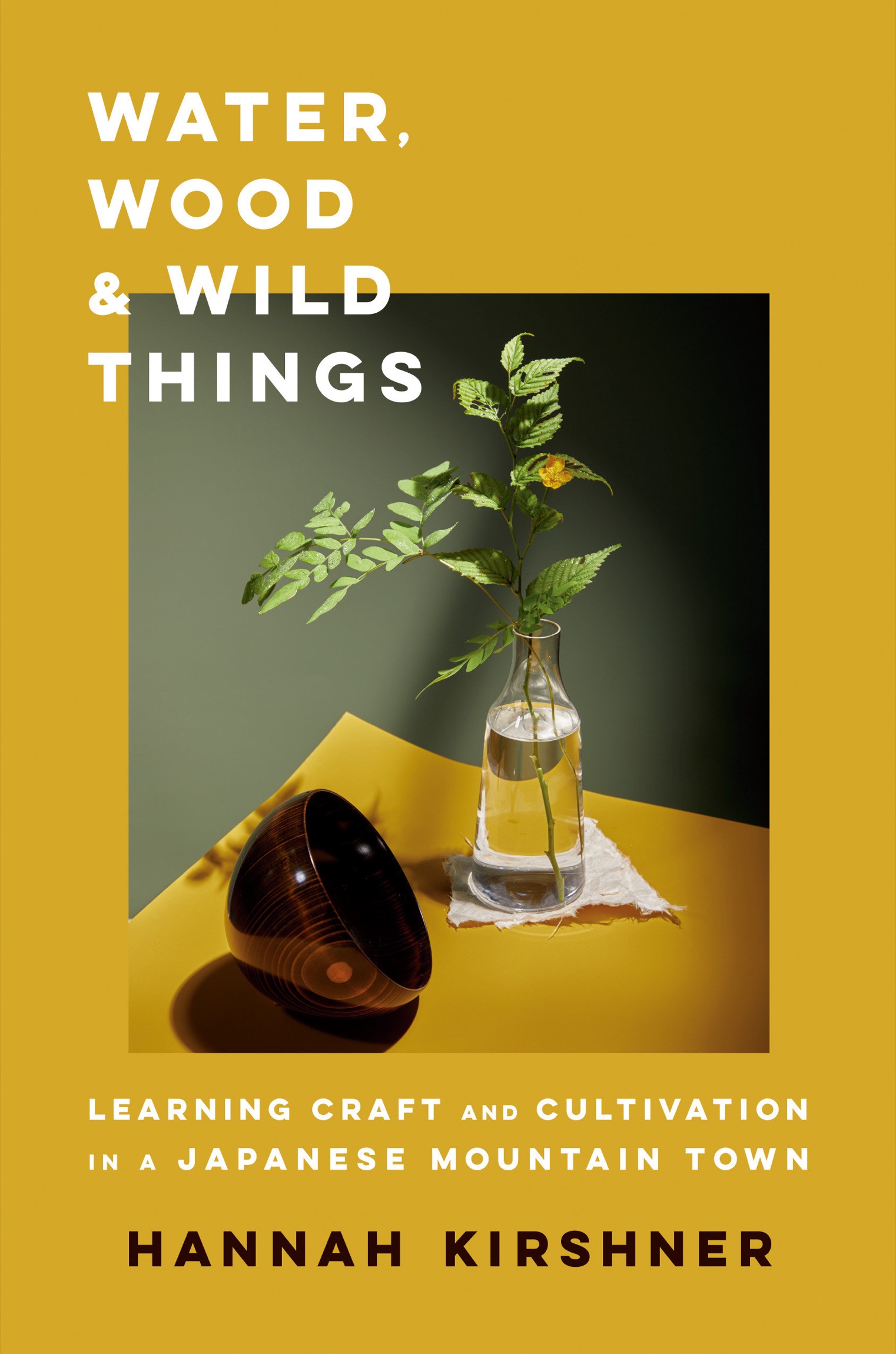

A Note on Names and Pronunciation

In Japanese, ones family name appears first, followed by given name (my name becomes Kirshner Hannah). But most of my friends and acquaintances in Japan use the Western convention when they introduce themselves in English and on English versions of their business cards. Im following their leadeven for historical figuresto make things easier for English-speaking readers. In this book I call people by the name (sometimes family, sometimes given) that you might use if you, the reader, were to meet them. Ive honored the spelling people and organizations use for their own names, even if it doesnt follow contemporary conventions for romanization; I do the same for words already familiar in English.

There is no consistent style of romanization across trade publications, and academic standards may be cumbersome for readers new to Japanese. Ive tried to find a middle ground thats consistent and easy to read. Macrons (the short lines above some letters; for example, , ) indicate long-sounding vowels. I use an accent on sak for the sake of clarity, but elsewhere confusion is unlikely. The e at the end of a Japanese word is never silent. The pronunciation of vowels is similar to that in Spanish, but syllables are weighted equally. G is always hard. L and r are pronounced identicallymore softly than an English r but farther back on the roof of the mouth than our light l. I choose not to italicize Japanese words as I introduce them (as is often done for foreign words) because they are not foreign within the context of this book.

redcedar

Prologue

Yamanakas forest, draped in moss and feathered with ferns, made me feel at home as soon as I arrived. Like the town where I grew up, North Bend, Washington, there are mountains every way you look, and yet you dont have to drive far to reach the sea.

To get to Yamanaka I traveled three hours on two trains west from Tky. It wasnt my first time in Japannearly a decade earlier Id spent a month with bike messengers in Kyto and Tkybut I was headed into the deep countryside, far from anyone or anything I knew well. I remember gazing out the window of the new bullet train at mountainsides covered in triangular blue-green conifers. They looked exactly like the motif on the furoshiki (wrapping cloth) my husband carries when he travels. Id assumed the illustration was stylized; I didnt know trees could be so uniform and symmetrical.

Yamanaka means in the mountain. Misty ridges encircle tile-roofed wooden houses and weathered shrines. The smell of cypress and sak permeates the air. Artisans and farmers carry on centuries-old traditions, making tableware by hand and cultivating rice and vegetables. I went there hoping that my two-month apprenticeship at a sak bar would be a gateway into deeper understanding of Japanese food and drinks.

At the southern edge of Ishikawa, a prefecture that spoons the Sea of Japan, Yamanaka belongs to a region thats been dismissively referred to as ura-Nihon, the backside of Japan. Because of its isolation, Ishikawas agricultural, fishing, and craft communities have been slow to give up old-fashioned ways. Now the precise thing that drew disdain makes Ishikawa a destination for avant-garde chefs and discerning travel editors searching for the version of Japan held up in the countrys own mythology and romanticized in the West.

Yamanaka claims a thirteen-hundred-year history of tourism because of its hot springs, but most of its visitors still come from within Japan and other Asian countries. Looking at its tourism data over the past hundred years is like watching the ups and downs of the Japanese economy: the number of visitors gradually increased after World War II, then peaked in the 1970s and again in the 1990s. Most years in the past half century about 500,000 people visited Yamanaka.

Fewer than eight thousand people live in the town and its surrounding villages, and that number is shrinking. And yet young artists, designers, and entrepreneurs move there to make a life in the countryside. Students come from all over Japan to study at the wood-turning school and apprentice with master craftsmen. There are few salarymen in Yamanaka: most people are hospitality workers, business owners, or artisans.

The evergreens I saw from the train are sugi, Japanese cedar, I was told. But theyre different from what I know as cedar. The bark of sugi does resemble the strips I peeled off the trunks of western redcedar as a childbending it back and forth until it became pliable, marveling that indigenous people made clothes from these scratchy fibers. I would crush flat, scaled redcedar leaves between my palms to release their fragrance and find them later crumbled in my pockets. I didnt recognize the spiky fingers of sugi leaves.

It turns out that neither sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) nor western redcedar (Thuja plicata) is a true cedar: theyre both in the cypress family. In Yamanaka, I had many revelations that what Id been told about Japan was not exactly right. That there werent always analogues in American culture. That translations were often hasty and imprecise.