The right of Andy Lawrence to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

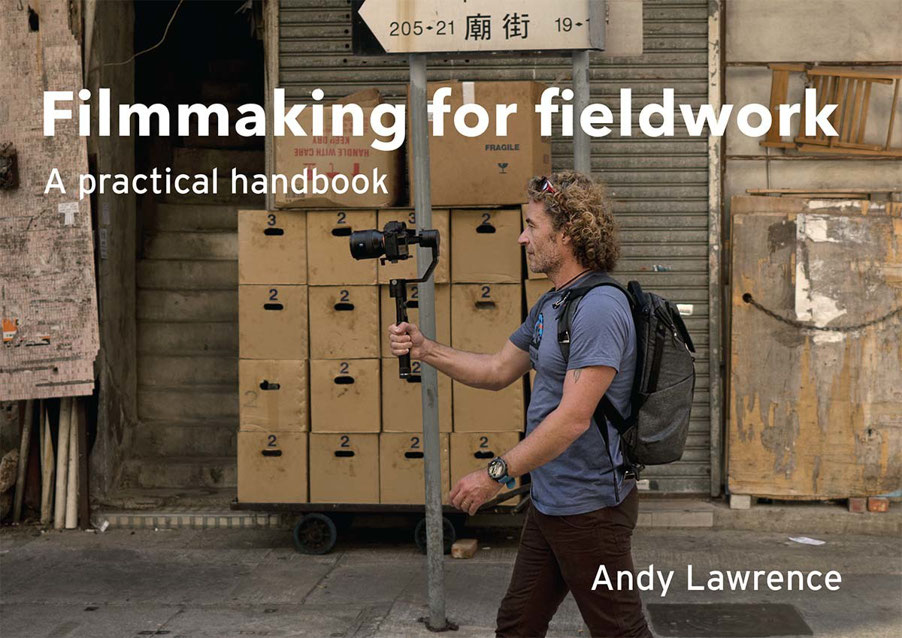

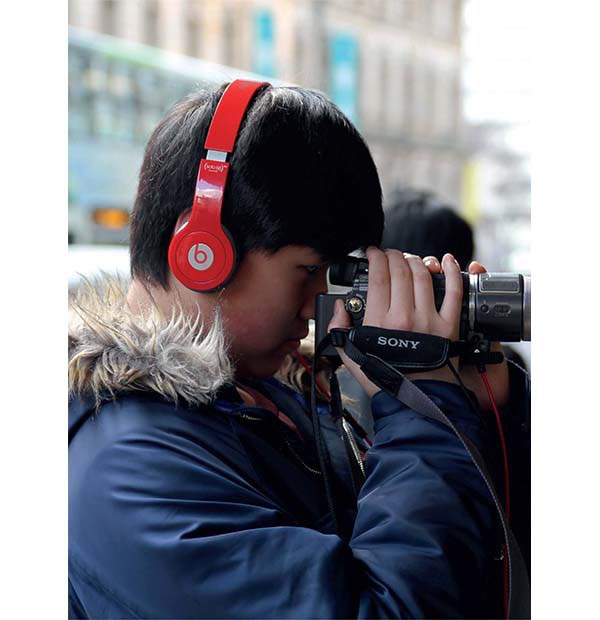

Front cover: Lloyd Belcher recording street scenes in Hong Kong.

Photo by Gabriella Belcher.

I think of myself as an amateur filmmaker, not a professional, in the sense that amateur means love of something, for the form.

Jim Jarmusch

Contents

This handbook is intended for anybody who wants to use ethnographic documentary for broadcast, research or personal filmmaking projects. Its focus is practical and theoretical with a degree of technical advice appropriate for those making their first films. It will also suit media professionals aiming to convert established practice into research. The aim is to encourage exploration through practice, and the book adopts a pedagogy that I have developed over the past twenty years while teaching filmmaking to research students and professionals and by making my own films independently for TV, festival and internet broadcast. It is intended to inspire the development of core skills in camera use, sound recording and editing that can be applied to sensory, fictive, observational, participatory, reflexive, performative and immersive modes of storytelling.

In his landmark text Ethnographic Film, first published in 1976 and now available as a revised edition, Karl Heider finds a degree of ethnographicness meaning the balance between description and analysis as it is contextualised from within the lived circumstances of others that may or may not be evident through the content of a film. This has proved useful in social anthropology, but one of the intentions of this book is to extend the reach of ethnographic filmmaking into other areas, and for this reason I have looked for different ways to describe the purpose, ideas, equipment and techniques associated with ethnographic documentary. The handbook also aims to simplify and update existing practical introductions to ethnographic film, such as the comprehensive Cross-Cultural Filmmaking by Ilisa Barbash and Lucien Castaing-Taylor (1997), which concentrates mainly on the production of celluloid film.

I have added a number of Appendices that will be useful to a practising filmmaker. These include a summary kit list and templates of important forms and documents to organise the bureaucracy of a film project. I have also compiled a list of films in chronological order and texts in alphabetical order, including works that I have cited in this handbook, in the hope that these might inspire readers with a wide range of interests.

The handbook is designed to accompany filmmakers into the field in the pocket of a camera bag. I hope that it will inspire your own documentary practice, so please put it down once you have arrived at a stage in the filmmaking journey that interests you and pick it up again when you get stuck.

Good luck!

Images and written texts not only tell us things differently, they tell us different things.

David MacDougall

author of Transcultural Cinema (1998: 257)

We write to test our thinking, and the same is true when we film. A modern approach to social research requires us to think about human action through its affect, bodily sense and experience, and for this we need techniques that work in real time as well as those that operate retrospectively. We cannot know the experience of another person completely, even if we share the same time and space, because of the way that things feel differently for each of us. A filmmaker, however, seeks proximity to others as a way to interpret their thoughts, emotions and actions through images, sounds and stories that are eventually shared in a different but related cinematic experience. Opportunities for these documentaries are found in daily processes, spoken words and critical events, or they might be discovered outside of our existing conceptual frameworks as we encounter new things along the journey.

Filmmaking for fieldwork is more than using a camera and sound devices to gather data on location. It is about a collection of procedures and skills involved in cinema praxis that can inspire our thinking and transform our ability to understand the world. It is a simple method that relies on the belief that good construction material for a film can also provide rich terrain for growing new ideas, and as such it is informed by just two principles:

1Knowledge is explored and expressed using techniques that operate at the level of sensory perception.

2Ethical considerations about the lives and experience of others inform the style and approach of the work.

The emphasis of this handbook is on the practical and technical aspects of documentary filmmaking. However, in this section we will look at some theoretical ideas and their associated techniques that demonstrate the relevance of cinema practice for academic research. The text uses ideas that have supported the making of my own films in order to inspire readers to think about their reasons for using a particular filmmaking method. Equally, you may wish to reflect on an already established cinema practice where you are required to think about filmmaking in new ways.

In Argonauts of the Western Pacific, Bronisaw Mainowski (1922) described how a wealth system based on the exchange of seashells informs the daily lives of island people, beyond their simple economic needs. The so-called kula ring required that in order for shells to retain their monetary value they must be in perpetual circulation, which required various means of direct interpersonal communication. When this work was first published it presented an interesting alternative to a Western audience who were more familiar with depersonalised systems of hoarding capital in banks. Mainowskis research ethics and findings were brought into question when his personal diaries revealed a colonial sensibility that is anathema to contemporary research, but his methods have survived to this day. During an extended stay on the islands of New Guinea, Mainowski developed an approach to understanding other cultures that he called ethnographic. This involved participating in the lives of other people, alongside a more detached, observational and academic analysis of their customs and practices. Filmmaking for fieldwork draws on this ethnographic tradition by using a camera and microphones to describe the ways that people become involved in and affected by processes, such as the kula ring, from a position of close involvement. It uses the procedure of narrative editing as an analytic tool, in order to explore ideas about the relations between people and objects, with the ultimate aim of developing documentary stories about the complicated feelings and emotions that extend from such intersubjective activity.

![Jon Fitzgerald - Filmmaking for Change: Make Films that Transform the World [2nd Ed.]](/uploads/posts/book/436017/thumbs/jon-fitzgerald-filmmaking-for-change-make-films.jpg)