Contents

Guide

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

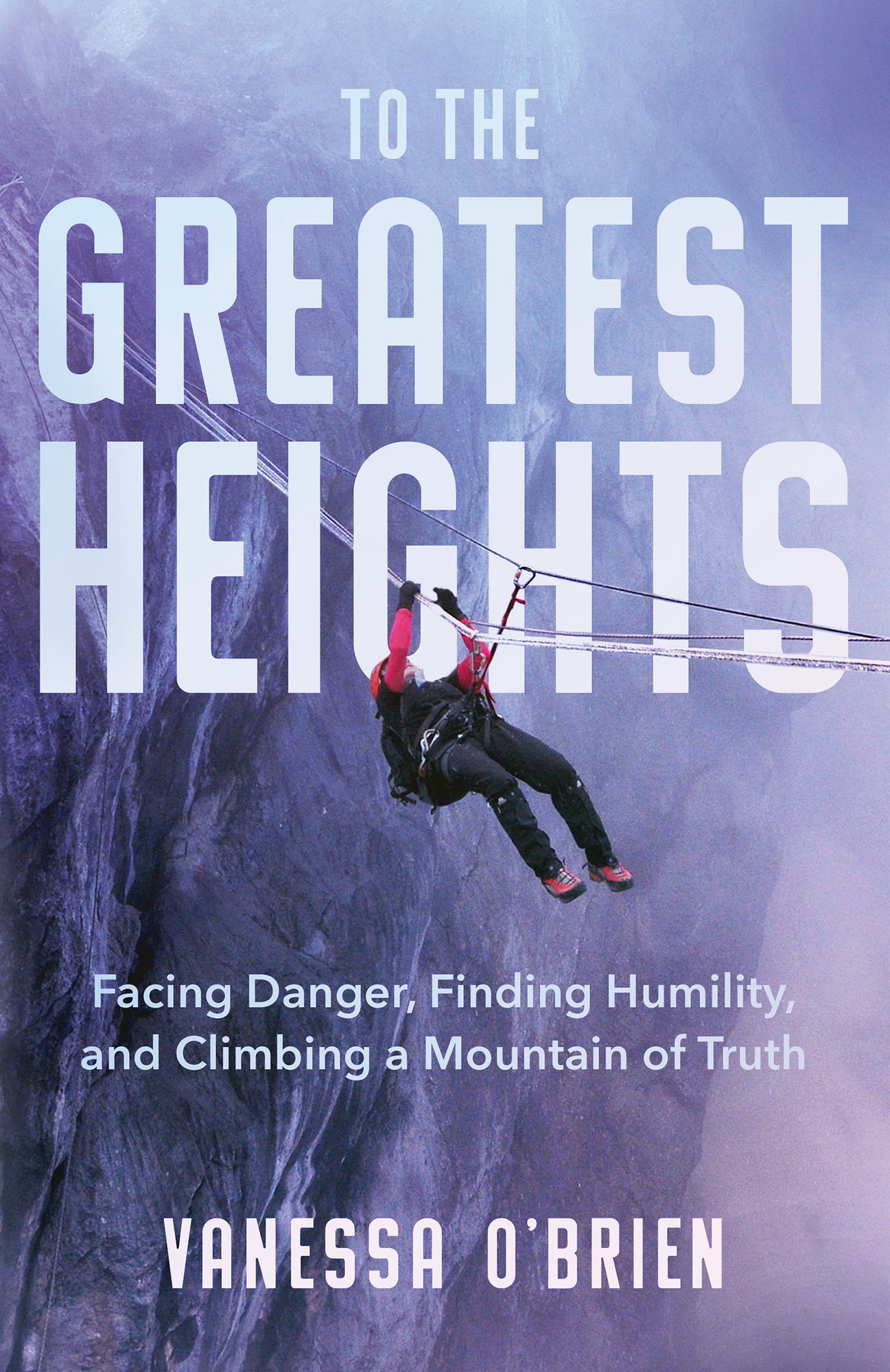

Copyright 2021 by Vanessa OBrien

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

Some names and identifying details have been changed and some individuals and events have been composited.

First Emily Bestler Books/Atria Books hardcover edition March 2021

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Jill Putorti

Jacket design by Emma A. Van Deun

Jacket photograph Photo Credit Kurt Wedberg, Sierra Mountaineering International, Inc.

Author photograph by Penny Vizcarra at PV Public Relations

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-9821-2378-9

ISBN 978-1-9821-2380-2 (ebook)

To all those with the courage to embrace change.

PROLOGUE

Mountain climbing is extended periods of intense boredom interrupted by occasional moments of sheer terror.

ANONYMOUS

I scrambled over a rocky moraine onto the Godwin-Austen Glacier high in the Himalayas. K2 towered over me, marbled white and black against blue sky, an almost perfect triangle, like a mountain drawn by a child. I tried to focus on my feet, but the summit teased the corner of my eye and made me feel a bit off-kilter. It dodged in and out, playing hide-and-seek with the midsummer cirrus clouds and crystalline snow plumes that rode a relentless wind. I dont recall the exact song I heard in my earbuds. It may have been the Rolling Stones singing about the difference between getting what you want and getting what you need, or maybe the Sex Pistols singing about the difference between what you want and what you get. Every expedition has its own soundtrack, and either one of those would be appropriate for my second attempt on K2.

Straddling the border between Pakistan and China, K2 is the highest point in the Karakoram Range, the second-highest mountain on the planet, at 28,251 feet and around 11,850 feet from Base Camp to summit. Its brutal cold, constant avalanches and falling rock, tricky technical climbs, and predictably dire weather conditions are legendary. Its a grueling test of physical endurance and mental will. Nothing keeps you there but sheer determination, because going there puts you and everyone who loves you in an excruciatingly uncomfortable position, as my husband, Jonathan, can confirm without complaining.

In 2013, three years before my second attempt on K2, a father and son were swept away by an avalanche near Camp 3, around 24,275 feet. On a bluebird day, I could just about see where they would have been. I had made a promise to the surviving wife and mother and her daughter, Sequoia Schmidt, that I would keep an eye out for any signs of either of them, so ever since wed arrived at Base Camp and begun seeing the evidence of what various avalanches had been pulling down the mountains, Id been investigating shredded summit suits, pieces of torn clothing, and yes, even the odd fragments of human remains. When I heard through the grapevine that another team had spotted two different boots side by side sticking out of an ebbing glacier, I felt a surge of hope and went out for a closer look.

The topography here is the legacy of a colossal slow-motion fender bender thats been going on for more than fifty million years. The Indian Plate smashed into and under the Eurasian Plate, forcing peaks five miles into the air to create the Himalayas, which include the Karakoram Mountains. As you observe when someone gets rear-ended in traffic, the wreckage juts up, folding into itself like an accordion. Fossils that formed in the primordial depths are now embedded in rock thousands of meters above sea level. Avalanches deposit snow into underground streams that gradually cut into the mountain, leaving deep crevasses and brittle ledges.

Mountains are never static, but the elderly ones that date back billions of years tend to be worn down and docile. In geological terms, the Himalayas are petulant adolescents. They talk back and misbehave, casting off rubble and debris without warning. Between the sharp peaks, frozen rivers and mountain waterfalls are constantly on the move, shifting three to six feet in a single day. A climber can easily slip into a deep crevasse and disappear into the icy abyss. They can get crushed by a tumbling serac or make some fatal mistake. They can succumb to sickness, edema, exhaustion, or hypoxia. They can fall, freeze, or simply fail to wake up.

At this writing, only 377 people have summited K2, and 84 climbers have died there, making it the second-deadliest mountain in the world, after Annapurna. For every twenty summits of Everest, theres only one summit of K2, and for every four summits of K2, one person dies, and the unpleasant reality is, very few dead bodies come off the mountain intact. Disembodied limbs, ghost gear, and frozen corpses appear and disappear in the shifting ice. The force of an avalanche tumbles the body like a stone in the oceanbones breaking, joints separating, tendons snapping, cartilage crumbling. The body tends to come apart at its weakest junctures, starting with the neck. The pieces are likely to be found by birds before another human being comes along to shift a disembodied head into a crevasse or shuffle scree over a torso. At high altitude, expending energy to pile rocks on a corpse or attempt to retrieve it would endanger the life of the well-intentioned climber, so my goal was not to recover the father and son, only to identify them with DNA samples.

The Sherpa are spooked by death. Many of them wont visit the memorial cairn near K2 Base Camp. Some fear that even taking a picture of a dead body might interrupt the souls journey. There was certainly no point in asking them to handle a dead mans ankle, so Id invited my Ecuadorian teammate Benigno to hike up the glacier with me. He was still below the moraine when I saw a stretch of crystal blue ice and snow the color of whipped cream up ahead. The pale backdrop made it easy to spot the bold blue and neon orange boots. Different colors, same European brand. Maybe two climbers whod shopped together for gear. Using my Garmin inReach, a satellite device that tracks movement and allows texting, I messaged Sequoia: Were they wearing Koflach boots?

While I waited for an answer, I made my way up the glacier to look for other signs of clothing, equipment, or remains. Climbing gear is as colorful as a circus act, specifically because we want to be easy to see against ice and rock. When I first started climbing, I hated this. I wanted to look like a ninja warrior, not a matching set of ketchup and mustard bottles on a grill, but La Sportiva Olympus Mons Evo boots were always going to be yellow. So its like Henry Fords Model T: you go with what gets you there. I hiked upward for a while, scanning the shadowed snowbanks. Nothing. It was overcast now, and I was pushing against a persistent wind that pushed back hard enough to engage a core of resistance between my ribs and breastbone. I went back to the boots.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.