Also by Jim Womack

The Future of the Automobile, with Alan Altshuler, Martin

Anderson, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos

The Machine that Changed the World, with Daniel T. Jones

and Daniel Roos

Lean Thinking, with Daniel T. Jones

Seeing the Whole, with Daniel T. Jones

Lean Solutions, with Daniel T. Jones

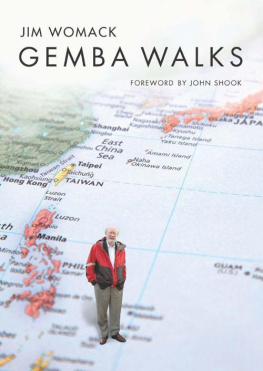

GEMBA WALKS

by Jim Womack

Foreword by John Shook

Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc.

Cambridge, MA USA

lean.org

Version 1.0

February 2011

Copyright 2011 Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. Lean Enterprise Institute and the leaper image are registered trademarks of Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc.

ISBN: 978-1-934109-30-4

Design by Off-Piste Design

February 2011

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010939596

Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc.

One Cambridge Center

Cambridge, MA 02142

617-871-2900 fax: 617-871-2999 lean.org

For Dan, with profound gratitude for more than

30 years of gemba walking together.

FOREWORD

Lean conversation is peppered with Japanese terms. Consider the term kaizen, which is now understood as the structured, relentless approach to continually improving every endeavoreven beyond lean circles. The use of the term gemba may be a little less widespread, but its no less central to lean thinking.

Gemba (also spelled genba with an n) means actual place in Japanese. Lean thinkers use the term to mean real place or real thing, or place of value creation. Toyota and other Japanese companies often supplement gemba with its related term genchi gembutsu to emphasize the literal meaninggenchi like gemba means real place, and gembutsu means real thing. These terms emphasize reality, or empiricism. As the detectives in the old TV show Dragnet used to say, Just the facts, maam.

And so the gemba is where you go to understand work and to lead. Its also where you go to learn. For the past 10 years Jim Womack has used his gemba walks as opportunities for both. In these pages, he shares with us anew what he has learned.

The first time I walked a gemba with Jim was on the plant floor of a Toyota supplier. Jim was already famous as the lead author of The Machine That Changed the World; I was the senior American manager at the Toyota Supplier Support Center. My Toyota colleagues and I were a bit nervous about showing our early efforts of implementing the Toyota Production System (TPS) at North American companies to Dr. James P. Womack. We had no idea of what to expect from this famous academic researcher.

My boss was one of Toyotas top TPS experts, Mr. Hajime Ohba. We rented a small airplane for the week so we could make the most of our time, walking the gemba of as many worksites as possible. As we entered the first supplier, walking through the shipping area, Mr. Ohba and I were taken aback as Dr. Womack immediately observed a work action that spurred a probing question. The supplier was producing components for several Toyota factories. They were preparing to ship the exact same component to two different destinations. Dr. Womack immediately noticed something curious. Furrowing his brow while confirming that the component in question was indeed exactly the same in each container, Dr. Womack asked why parts headed to Ontario were packed in small returnable containers, yet the same components to be shipped to California were in a large corrugated box. This was not the type of observation we expected of an academic visitor in 1993.

Container size and configuration was the kind of simple (and seemingly trivial) matter that usually eluded scrutiny, but that could in reality cause unintended and highly unwanted consequences. It was exactly the kind of detail that we were encouraging our suppliers to focus on. In fact, at this supplier in particular, the different container configurations had recently been highlighted as a problem. And, in this case, the supplier was not the cause of the problem. It was the customerToyota! Different requirements from different worksites caused the supplier to pack off the production line in varying quantities (causing unnecessary variations in production runs), to prepare and hold varying packaging materials (costing money and floor space), and ultimately resulted in fluctuations in shipping and, therefore, production requirements. The trivial matter wasnt as trivial as it seemed.

We had not been on the floor two minutes when Dr. Womack raised this question. Most visitors would have been focused on the product, the technology, the scale of the operation, etc. Ohba-san looked at me and smiled, as if to say, This might be fun.

That was years before Jim started writing his eletters, before even the birth of the Lean Enterprise Institute (LEI). The lean landscape has changed drastically over the past 10 years, change reflected in Jims essays. From an emphasis on the various lean tools for simple waste elimination in manufacturing firms, attention has steadily shifted to a focus on the underlying management principles, systems, and practices that generate sustainable success in any type of organization. Also, the impact of lean continues to grow, moving from industry to industry, country to country, led by a growing number of practitioners and academics and other lean thinkers. Entirely new questions are being asked today of lean, as a result of the practice of the Lean Community, most of whom have been transformed by Jims work.

Receiving praise for all he has accomplished in inspiring the lean movement that has turned immeasurable amounts of waste into value, Jim always responds with the same protest: Ive never invented anything. I just take walks, comment on what I see, and give courage to people to try.

I just take walks, comment on what I see, and give courage to people to try. Hmm, sounds familiar. Toyotas Chairman Fujio Cho says lean leaders do three things: Go see, ask why, show respect.

Yes, Jim takes many walks, as he describes in these pages. And in doing so he offers observations on phenomena that the rest of us simply cant or dont see. He has a remarkable ability to frame issues in new ways, asking why things are as they are, causing us to think differently than we ever did before. Saul Bellow called this kind of observation intense noticing. Ethnographers teach it as a professional tool. Lean practitioners learn it as a core proficiency.

But simply seeingand communicatinglean practice is but one way that Jim has inspired others. Jim gives encouragement in the real sense of the term: courage to try new things. Or to try old things in different ways. I dont know if theres a stronger embodiment of showing respect than offering others the courage to try.

Without Jims encouragement, I certainly would not be here at the Lean Enterprise Institute. I probably would not have had the courage to leave Toyota many years ago to discover new ways of exploring the many things I had learned or been exposed to at Toyota.

But I am just one of countless individuals Jim has inspired over the past two decades. And with this collection of 10 years of gemba-walk observations, be prepared to be inspired anew.

John Shook

Chairman and CEO

Lean Enterprise Institute

Cambridge, MA, USA

February 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Gemba. What a wonderful word. The placeany place in any organizationwhere humans create value. But how do we understand the gemba? And, more important, how do we make it a better placeone where we can create more value with less waste, variation, and overburden (also known, respectively, as muda, mura, and muri)?

Ive been thinking about these questions for many years, and learned long ago that the first step is to take a walk to understand the current condition. In the Lean Community we commonly say, Go see, ask why, show respect. Ive always known this intuitively, even before I had a standard method, and even when I labored in the university world where it seemed natural to learn by gathering data at arms length and then evaluating it in an office through the lens of theory. Now I work in an opposite manner by verifying reality on the gemba and using this understanding to create hypotheses for testing about how things can work better.

Next page