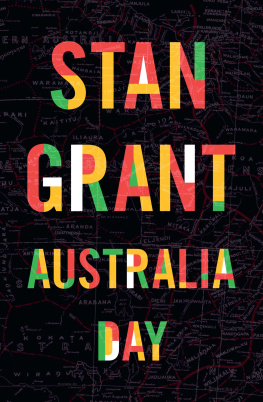

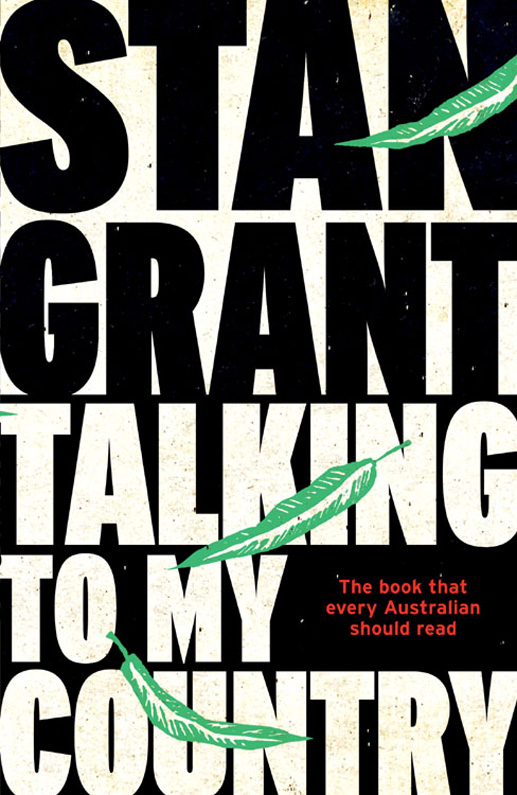

Stan Grant - Talking to My Country

Here you can read online Stan Grant - Talking to My Country full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2016, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Talking to My Country

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Talking to My Country: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Talking to My Country" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Talking to My Country — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Talking to My Country" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Tears of Strangers

Lines from Theme for English B (Hughes) reproduced with kind permission by Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

Lyrics from She Cried, written by Frank Yamma (Mushroom Music Publishing), reproduced with kind permission.

Lyrics from Took the Children Away, written by Archie Roach (Mushroom Music Publishing), reproduced with kind permission.

HarperCollinsPublishers

First published in 2016

by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Pty Limited

ABN 36 009 913 517

harpercollins.com.au

Copyright Stan Grant 2016

The right of Stan Grant to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000.

HarperCollinsPublishers

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

A 53, Sector 57, Noida, UP, India

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF, United Kingdom

2 Bloor Street East, 20th floor, Toronto, Ontario M4W 1A8, Canada

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007, USA

ISBN: 978 1 4607 5197 8 (hardback)

ISBN: 978 1 4607 0681 7 (ebook)

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Grant, Stan, author.

Talking to my country / Stan Grant.

Subjects: Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of.

Aboriginal Australians Social conditions 21st century.

Racism Australia

Reconciliation.

Social conflict Australia.

Australia Race relations 21st century.

305.89915

Cover design by Darren Holt, HarperCollins Design Studio

Cover images by shutterstock.com

To my grandmother Ivy and my wife Tracey

white women who have loved us.

So will my page be Colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be

a part of you...

You are white

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you...

Sometimes, perhaps you dont want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, thats true!

Langston Hughes: Theme For English B

These are the things I want to say to you. These things I have held inside or even worse run from. It is not easy, what I have to say, and it should not be easy. These are things that tear at who we are. These are the things that kill, that spread disease and madness. These are the things that drive people to suicide, that put us in prisons and steal our sight.

I have started this so many times and stopped. I have tried to find the right words. It is so tempting to turn to rage and blame. I am angry: I know that. It flares suddenly and with the slightest provocation; it takes my breath away sometimes. I know where that comes from. I have seen it in my father and he inherited it from his father. It comes from the weight of history.

I am afraid too. And that comes from the same place. I have known this fear all my life. When I was young it used to make me feel sick, physically ill in the pit of my stomach. It was a fear of what could touch us the sense of powerlessness, of being at the mercy of the intrusion of the police or the welfare officers who enforced laws that enshrined our exclusion and condemned us to poverty. It was a heavy hand that made people tremble. I see it still in my father. I see it as he tenses up just at the sight of a police car. He has done nothing wrong. But when he is pulled over for something as routine as a random breath test his heart beats faster and he fumbles his keys. We fear the state and we have every reason to. The state was designed to scare us.

I want to tell you about blood and bone and how mine is buried deep in this land. I want to tell you of a name that should be mine, a Wiradjuri name that passed down from thousands of years of kinship taken from us along with our language and our land. And I want to tell you how I came to the name I have: Grant, the name of an Irishman, a name from a time of theft and death.

Australia still cant decide whether we were settled or invaded. We have no doubt. Our people died defending their land and they had no doubt. The result though was the same for us whatever you call it. Within a generation the civilisations of the eastern seaboard older than the Pharaohs were ravaged.

Across Australia nations that had not seen a white man Bandjalang, Kamilaroi, Ngarrindjeri, Arabana, Darumbal, Gurindji, Yawuru, Watjarri, Barkindji, and all of the other hundreds of distinct peoples, each with their law and song and dance, all of them separate with their own boundaries defined by kinship and trade in the eyes of the British simply never existed.

Soon we would lose our names; names unique, inherited from our forefathers. Then our languages silenced. Soon children would be gone. This is how we disappear. Now Australians pay their respects to the elders of nations of which they have no idea.

I want to tell you how you have always sought to define us. You called us Aborigines: a word that meant nothing to my people. And in that one word you erased our true identities. Today we have to prove constantly who we are. Australias own government records show how we have been defined and redefined sixty-seven times: sixty-seven versions of us. We were classified according to a so-called quantum of blood, Full Blood, Half Caste, Quarter Caste, Octoroon. Some were deemed to be Aborigines if they lived on a government mission or reserve; others were reclassified white if they lived in town. Some people were granted a special status exempted from restrictive or discriminatory laws. Today there is a three-part definition: indigenous descent, indigenous identity and acknowledgment by the indigenous community.

Whenever we enrol in school, apply for a job or join a sports team there is a box to tick that asks if we are Aboriginal or Islander. No one else is asked this. If we tick yes we have to prove it. My children have to ask their grandfather a member of the Wiradjuri Council of Elders to verify the identity of his own flesh and blood.

I was raised to know I was the son of a Wiradjuri man and a Kamilaroi woman this is my family, my heritage yet in the eyes of the state my identity remains in flux. To proclaim myself an indigenous person is a political act, something to be negotiated between our bloodline and the law imposed on us.

So, my country, these things are important. Faces and names and language and land are important. Without land we have no inheritance. People with no land are poor. It isnt just here: we share this with indigenous people throughout the world. Together we are just five per cent of the global population and fifteen per cent of total poverty. But these are numbers, and faces and names are far too often forgotten.

Australians know so little about us. They know so little about what has happened here in their name. Perhaps they can talk about the American west: Sitting Bull and Custer and Little Big Horn. They may know of Caesar and Napoleon and Tutankhamen. But Pemulwuy? Windradyne? Jandamarra? What of these warriors and leaders who fought and died here for their land? What about the massacres of Myall Creek, Coniston or Risdon Cove?

I have always thought settler communities unique, they see new lands as something to be claimed, as places without a past. The people who have come here have left history behind. Settlers look out; they look forward. The mark of success is to leave a better life for your children. Settlers prove how much they belong by how far they have travelled, how much they have acquired.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

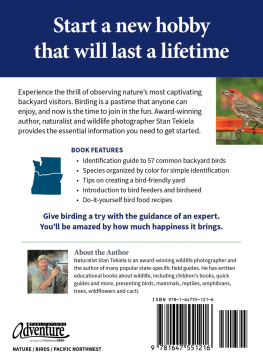

Similar books «Talking to My Country»

Look at similar books to Talking to My Country. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Talking to My Country and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.