Stan Grant - On Identity

Here you can read online Stan Grant - On Identity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Melbourne University Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

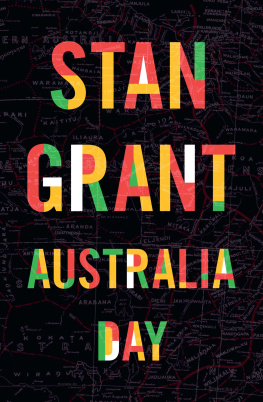

- Book:On Identity

- Author:

- Publisher:Melbourne University Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

On Identity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "On Identity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

On Identity — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "On Identity" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Stan Grant is a self-identified Indigenous Australian who counts himself among the Wiradjuri, Kamilaroi, Dharrawal and Irish. His identities embrace all and exclude none. He is a multi-award-winning journalist and foreign correspondent who has covered the worlds biggest stories of the past three decades. He has worked for the ABC, SBS, CNN, Seven Network and SKY News. Grant published the bestselling Talking to My Country (2016), which won the Walkley Book Award, and he also won a Walkley award for his coverage of Indigenous affairs. In 2016 he was appointed to the Referendum Council for Indigenous Recognition.

Little Books on Big Ideas

Blanche dAlpuget On Lust & Longing

Fleur Anderson On Sleep

Gay Bilson On Digestion

Julian Burnside On Privilege

Paul Daley On Patriotism

Robert Dessaix On Humbug

Juliana Engberg En Route

Sarah Ferguson On Mother

Nikki Gemmell On Quiet

Germaine Greer On Rape

Germaine Greer On Rage

Sarah Hanson-Young En Garde

Jonathan Holmes On Aunty

Susan Johnson On Beauty

Malcolm Knox On Obsession

Barrie Kosky On Ecstasy

David Malouf On Experience

Katharine Murphy On Disruption

Leigh Sales On Doubt

Mark Scott On Us

Tim Soutphommasane On Hate

David Speers On Mutiny

Natasha Stott Despoja On Violence

Anne Summers On Luck

Don Watson On Indignation

Tony Wheeler On Travel

Ashleigh Wilson On Artists

Elisabeth Wynhausen On Resilience

Stan Grant

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2019

Text Stan Grant, 2019

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design by Alice Graphics

Cover design by Nada Backovic

Typesetting by TypeSkill

Author photograph by Kathy Luu

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522875522 (paperback)

9780522875539 (ebook)

T here are women behind me and I can hear them talking.

Im sure Im related to him, one says.

Yes, replies the other, through your grandmotherthat was his grandfathers sister.

Its me theyre talking about. I have come here to a place where my father and grandfather were born, a place that I could call my countrya physical space and a state of mind. It is a place far older than what we call Australia, so old that my kinship doesnt run in a straight line but moves in ever-widening circles. I am here to talk about identitywhat it is to belong. And it starts with family.

When I turn around they smile and, even though I have never met them, I see faces I have known all my life.

Im your Great Aunty Ems granddaughter, one says.

The other is the granddaughter of my Great Aunty Liz. Elizabeth Knight and Emma Merritt were both my grandfathers sisters.

These women are doing what people I call my own always do, something that is hardwired in us: mapping our family, connecting me to them. Put two or more of us together and it is the first question asked: Where are you from, who are your people? It is genealogy, but it is more than that. It is survival.

We all do this in our own waypeople everywhere. It is the family crest, the clans tartan, a sepia-tinged photograph, a convict ships manifest, a long-dead soldiers pocket book, the tattooed wrists of the death campstangible proof, because we so need it. We are not just alive now but alive for all time. Once a distant ancestor would have carved the outline of an animal on a wall or traced her handprint, so that some day someone would see it and know that who was here mattered. We do this because we know the truth: all things must pass; time and death are unstoppable. We live with impermanence, we will go, all of us, and so we seek to cheat it all, to tell ourselves that we were here before and will be here again.

The science that has given us the power to obliterate humankind has also given us the gift of eternity. Now we can push back even beyond shared memory, following our bloodline into all corners of the globe. We have decoded the human genome, a scientific book of Genesis that reveals who begat who until we reach our mythical Adam and Eve. We buy DNA kits that tell us we are never who we think we arethe Italian woman who discovers she is Ashkenazi Jew; the Scotsman surprised that he has long-lost relatives in Kenya; the African-American who is as much Norwegian and Navajo.

There are three billion letters in our genetic code and almost all of them are identical. The scientific truth is 99.9 per cent of our DNA is similar to everyone else. Think about that, all of our difference, all of the things we hold trueor at least we think they arecontained in that fraction of a per cent. What horrors we have committed in that tiny space between us: those wars, slavery based on race, conquest and colonisation. But that tiny space between us has given us such beauty too: art and language and music, new words for God, new ways of explaining our universe. All that brings colour to a grey world.

Michelangelo knew something when he painted the Sistine Chapel. He left a space between those outstretched hands of God and Adam. Before scientists had measured the distance, Michelangelo gave us that space to find ourselves. That space we call our world is the phenomenological world of philosopher Immanuel Kantwe bring into being only what we know, it is through our experience we understand. But the world can also be too much for us. Albert Camus knew this world as the absurd. Understanding the world for a man, the French philosopher and author wrote, is reducing it to the human. Camus wondered of who and of what can we truly say, I know that. I know my heart; I can feel that; it exists. He said, This world I can touch, and I likewise judge that it exists. There ends all my knowledge, and the rest is construction.

And the rest is construction.

We have entered the world of identitythat fraction of DNA, that space between the hands of God and Adam. That space holds the battle for power, our politics or ideology, our faith or our atheism, all our love and hate. In that space we become strangers, even strangers to ourselves. In that space, says Camus, is all of our absurdity, and the absurd becomes God and the inability to understand becomes the existence that illuminates everything.

In a perfect world I would have no need to write of identity, but the world is not perfect and identity is one of the reasons why. It consumes me. It is the thing I must write about if I am to be free to write about anything else. There is no other way; identity was foisted on me before I could even choose what I wanted to be. There were names for people like meAborigine, half-caste, Aboriginal, Indigenousand many more that I wont repeat here because to do so would only give them power and those names have caused enough damage already. It is enough to know that I am none of those things, even if at times I have had to be all of those things.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «On Identity»

Look at similar books to On Identity. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book On Identity and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.