Mining Language

RACIAL THINKING, INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE, AND COLONIAL METALLURGY IN THE EARLY MODERN IBERIAN WORLD

Allison Margaret Bigelow

Published by the OMOHUNDRO INSTITUTE OF EARLY AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE, Williamsburg, Virginia, and the UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA PRESS, Chapel Hill

The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture is sponsored by the College of William and Mary. On November 15, 1996, the Institute adopted the present name in honor of a bequest from Malvern H. Omohundro, Jr.

2020 The Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

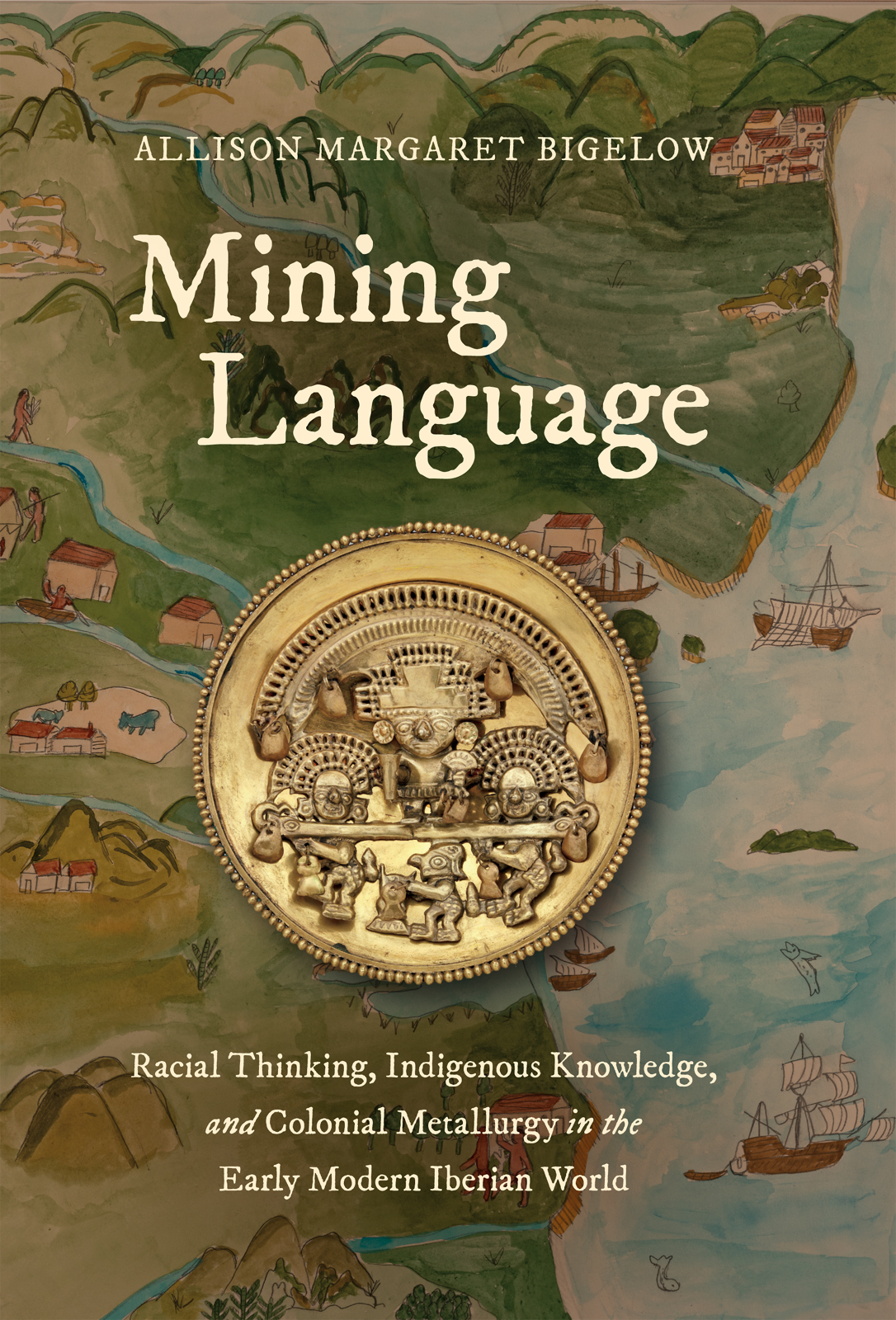

Cover images: Watercolor painting of Cocorote, Venezuela, by Rebecca Graham (2017); contact-era ear flare depicting a cacique (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bigelow, Allison Margaret, author.

Title: Mining language : racial thinking, indigenous knowledge, and colonial metallurgy in the early modern Iberian world / Allison Margaret Bigelow.

Description: Chapel Hill : Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture : University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052077 | ISBN 9781469654386 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469654393 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mineral industriesLatin AmericaLanguageHistory. | Mines and mineral resourcesLatin AmericaHistory. | Language and cultureLatin America History. | IndiansLanguageInfluence on Spanish. | IndiansLanguageInfluence on Portuguese. | African languagesLatin AmericaInfluence on Spanish. | African languagesLatin AmericaInfluence on Portuguese.

Classification: LCC HD9506.L29 B54 2020 | DDC 622.01/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052077

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

For Lily

PREFACE

RECREATING THE ARCHIVE

Allison Bigelow and Rebecca Graham

Allison:

Between the spring of 2010, when I first read don Manuel Gaytn de Torress Relacin, y vista de ojos (1621) as a graduate student working in the John Carter Brown Library, and the fall of 2016, when I finished writing the chapter on colonial copper projecting, I searched high and low for the painting that don Manuel described in his report. I looked in a variety of libraries and archives that held materials by Gaytn de Torres, including the Newberry Library (Chicago), British Library (London), Biblioteca Nacional de Espaa (Madrid), and Archivo General de Indias (Seville). At the AGI, I found manuscript drafts of don Manuels plan for Cocorote and two years responses to his colonial designs. At the Biblioteca Nacional, I uncovered legal cases of disputed inheritances that were important enough to have been printed as books. The British Library and Newberry collections hold multiple editions of the Relacin and other published works that bear don Manuels signature. But I never found the painting. The subject librarian for Iberian studies at UVa, Miguel Valladares-Llata, even stopped by the Biblioteca Real del Palacio Real in Madrid to download an eighteenth-century recopilacin of another proposal that don Manuel had authored; the handwritten edition included a family tree but no painting or navigational chart.

I thus was faced with a pressing methodological challenge: seventeenth-century manuscript sources provided testimony of the paintings existence, but the work itself was lost. Historians often speak of following our sources, but there are few guidelines on how to treat sources that testify to their own fragmentation. Don Manuels vision for a kind of autonomous slavery in Cocorote offers a very different model of community life and artisan labor than the dominant models of plantation monocultures that later took root in Venezuela and those that were practiced throughout the Americas. Nor does it resemble the forms of royal slavery that characterized the mines of El Cobre in eastern Cuba. The mines of Cocorote went on to become part of Simn Bolvars family estate, gesturing toward the intimate relationship between enslaved labor, commercial gain, and independence movements. The painting is an evidentiary form and means of persuasion that don Manuel specifically included in his proposal. By making visible don Manuels vision of Cocorote, the painting promises to capture a key moment in imperial imagining of possibility, and an importantif almost entirely overlookedpart of the story of Afro-Venezuelans and Afro-Latin communities in the early Americas. Archival evidence could only take me so far in my effort to tell this story, and I was stuck.

In the summer of 2016, while writing of this book, it struck me that a skilled painter who had studied colonial Latin America could use the Relacin, y vista de ojos to recreate the missing painting of Cocorote. Most important, I knew a Spanish-speaking artist who might be willing to give it a try. Rebecca Graham, an undergraduate student majoring in Spanish and Media Studies with an extensive background in studio art, and I then designed a three-credit independent study that we called Recreating the Archive (SPAN 4993). I had taught Rebecca in a survey of colonial Latin American literature and a research-intensive seminar in colonial translation. There, she formed part of a team of students who translated the testimonies of a colonial Spanish official and an Arawak woman regarding Walter Raleghs attack on Venezuela in 1617. The class project from Fall 2014, now published on the Early Americas Digital Archive, proved that Rebecca was a dedicated researcher and an excellent collaborator. I also served as her adviser for the major. Over the years, as we mapped out her schedule during advising office hours, I learned about her diverse background and deep interest in visual communications, from silkscreening and printmaking to film studies and American Sign Language. I had a sense of her intellectual curiosities and creative interests, and I suspected that this kind of experimental approach to archival remediation might be right up her alley.

We spent the fall semester of 2016 in Charlottesville, meeting every other week to talk about the text and sketch the mine site. We worked through print and manuscript editions of Gaytn de Torress plan, consulted military historians to determine how far two shots of an arquebus ought to be (our sincere thanks to Wayne Lee at the University of North CarolinaChapel Hill), and pored over early modern paintings of copper mines and colonial settlements in Venezuela.

In January 2017, we traveled to Spain with support from UVas Center for Global Inquiry and Innovation. We pulled sources at the Biblioteca Nacional in Madrid, studied seventeenth-century masterpieces in the Prado, and analyzed modern experiments that resembled our own efforts. At the Museo Reina Sofa, we were most inspired by Czech filmmaker Harun Farockis La plata y la cruz, which maps onto the present-day landscape of the Andean city elements of eighteenth-century Bolivian artist Gaspar Miguel de Berros painting of Potos, Descripcin del zerro rico e ymperial villa de Potos (1758). With this iconographic base, we traveled to Seville to consult archival documents, maps, and images.