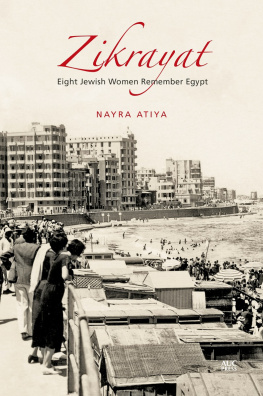

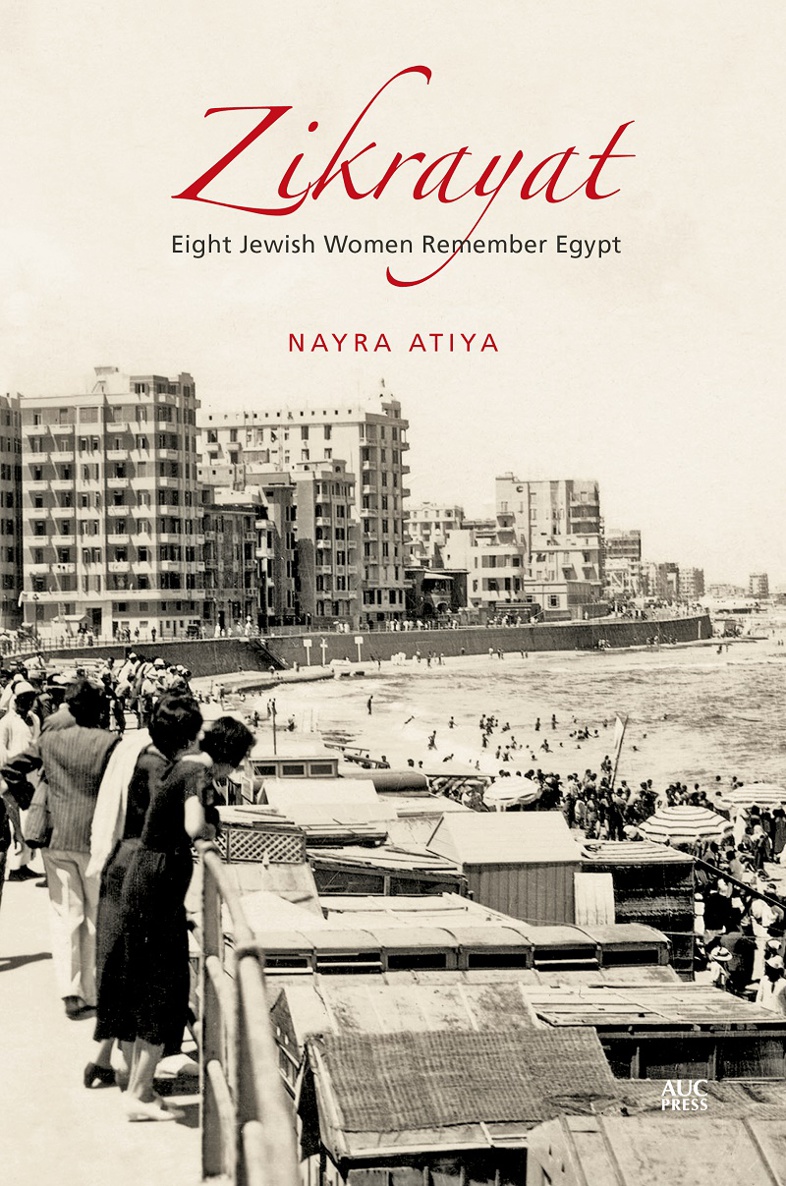

Zikrayat

Zikrayat

Eight Jewish Women Remember Egypt

NAYRA ATIYA

The American University in Cairo Press

Cairo New York

This electronic edition published in 2020 by

The American University in Cairo Press

113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt

One Rockefeller Plaza, New York, NY 10020

www.aucpress.com

Copyright 2020 by Nayra Atiya

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 977 416 955 7

eISBN 978 161 797 977 4

Version 1

For Melissa Solomon and for Eglal Errera,

friends over the years, women of courage, women

of the book. And to Asma, whose spirit lives on.

But think on me when it shall be well with thee, and shew kindness, I pray thee, unto me, and make mention of me unto Pharaoh, and bring me out of this house .

Genesis 40:14

CONTENTS

by Andrea B. Rugh

Although the history of kings and rulers is unequivocally fascinating, I think we are also hungry for the narrative history of ordinary people... If history fails to represent all of us, it is not because historians are not interested, but because they lack the primary documents of so-called minor characters in history (Min Jin Lee, Pachinko 2017).

History tends to be good at describing events of turbulent periods, even while missing the personal traumas of people living through them. This is due less to disinterest than it is to a lack of information to complete the picture.

So it is with the history of the Jews who were compelled to leave Egypt in the late 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. Many people know parts of these events, but few know the actual conditions at different times that contributed to the exodus, or the effects on individuals and families. As time goes by and people die, or their memories fade, it becomes much harder to learn about their experiences.

Publishing the recollections of that period is especially urgent in this second decade of the twenty-first century, as mass migrations take place around the world. What do the experiences of Egyptian Jews tell us about peoples feelings upon migration to a new land, or their feelings many years after the move? What reasons finally propelled Jews in Egypt to leave? How did they accomplish their departures once the decision was made? How similar or different were their experiences? What emotions did they feel looking back on their lives in Egypt or their lives in the diaspora? What was it like for those who visited Egypt years later? Did they feel a connection to the land of their birth?

Nayra Atiyas stories of Egyptian Jews take us a step further in filling the gap. The stories as told to Nayra fell on particularly sensitive ears, as she was herself a young girl growing up in the Egypt at the time, albeit in the Coptic community with its own set of minority experiences. She uses her knowledge of the time and place to fill out details when raconteurs abbreviated them, or took for granted her knowledge of what they were describing. She has taken other liberties to make the text more readable, such as ordering the sequence of events and strengthening the story line when her informants take extended detours. The result is a charming telling of stories that inevitably have their emotional highs and lows.

The stories suggest parallel themes in the lives of New York Jews who emigrated from Egypt and told Nayra their stories in the decade starting with 1987roughly twenty to forty years after their departuresand yet each tells a distinctly different story, at least partly because tensions surrounding foreign communities changed during different periods. A short history helps explain the circumstances that led to such different experiences for the Jews who left Egypt, and in particular the eight women Nayra met and interviewed in New York.

The short history

Most Westerners have a sketchy knowledge of the Jewish exodus from Arab lands in the twentieth century, but few know that the reasons for leaving differed over the decades. In addition, few understand what prompted indigenous Egyptians to turn on groups that for so long had been an integral part of their community. They may not be aware, for example, that the growing hostility toward foreigners in the 1920s and 1930s that culminated in the expulsion of the British decimated not only the Jewish community but others, such as the Greeks. After independence in 1952, the pace of the expulsions accelerated during Nassers presidency, with reforms meant to develop an Egyptian middle class and reduce economic inequalities through expanded employment opportunities, land redistribution, and sequestration of the assets of the wealthy. Foreign assets were an easy target for Nasser in his efforts to level the playing field for the Egyptian masses.

Although small communities of Jews, numbering around two thousand, existed in Egypt well before the nineteenth century, it was not until Muhammad Alis tenure (180548) that economic opportunities, especially in trade, attracted large numbers of Jews and other migrants from around the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. A second wave of migrants appeared in the early twentieth century, again attracted by economic opportunities and a desire to escape persecution in the countries of their origins. In one memoir, the authors father, born in Aleppo, Syria, was brought as an infant to Egypt. His father died shortly after their arrival but his mother kept her Halab culture in Egypt, giving the family a sense of superiority over local culture.

The years 1900 to 1937 under British occupation were a golden age for the migrants. Many maintained their foreign passports, either because they and other non-Muslim foreigners found it difficult to become naturalized citizens, or because these documents gave them protected status. By the late 1930s and 1940s, the tolerance extended to them as foreigners began to fade, and by the late 1940s, attacks on Egyptian Jews intensified because of their presumed links to Zionism. The capitulations system that had previously given foreigners legal protection under their own consular jurisdictions was abolished in 1949, putting them under the jurisdiction of the Egyptian court system.

In the early part of the twentieth century, some Jews motivated by a desire for social justice and cooperation between Egyptians of differing faiths became active in leftist causes. One prominent example was Henri Curiel (191478), an Egyptian-born Jew who led the communist Democratic Movement for National Liberation until he was expelled from Egypt in 1950 on trumped-up charges of Zionism. He was in fact a vocal anti-Zionist.

Tensions further intensified with growing Egyptian hostility toward British occupation, and by extension toward all non-Muslim foreigners who had privileges under the British occupation. The Jews, as well as other non-Muslim groups throughout this period, were seen primarily as foreigners, even though many were born and had lived in the country all their lives. Even Coptic Christians, who claimed Egyptian origins back as far as pharaonic times, were linked to outsiders as a result of British and American missionary activity, and through considerable Western funding.

Historians credit a series of wars and political events from the late 1940s until the late 1960s with forcing the departures of Jews and other foreigners from Egypt. For Jews, the first was the ArabIsraeli War of 1948 that culminated in the creation of the state of Israel. Of the roughly seventy-five thousand Jews who lived in Egypt at the time, about twenty thousand left after 194849. In this first major exodus from Egypt and other Muslim countries, many of the educated left because they were inspired by the idea of a Jewish homeland, while the rest were mainly poorer Jews seeking economic opportunities in Israel. Those with major assets mostly stayed in Egypt, hoping the situation would improve.