Acknowledgments

Our foremost thanks go to the individuals who captured these recipes and passed them down to their family members, and to those who ultimately donated them to the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections. In addition to the women and men who collected the recipes and the cookbooks containing some of them, we acknowledge the household employees who in many cases cooked these dishes. They are the unnamed champions.

There is no way to know whether these recipes were made by the women and men who collected them. We know that many of the families would have had African American cooks who prepared their meals. In the introduction to the 2005 edition of The Blue Grass Cook Book, Toni Tipton-Martin describes the African Americans as a generation of invisible cooks. There still may be undiscovered collections of African American family recipes within the University of Kentucky Libraries Special Collections, but for this cookbook early American culture and domestic relations remain intertwined in a complicated way. The relationship between white women and their black cooks is a dimension of the history of southern food and culture that has shaped current culinary tastes. We hope this book will inspire further research into this important area of American history.

Many individuals contributed to this project. We appreciate all of our tasters: Brigitte Abernathy, Greg Abernathy, Tracy Campbell, Henry Huffines, Carol McGraw, Marcus McGraw, Dean McMahan, Matthew McMahan, Helen Morrison, Neil Morrison, Rebekah Reeves, Matt Ritchie, Alison Scaggs, Carla Scaggs, Marilyn Scaggs, Roger Scaggs, Dave Wachter, and Shanna Wilbur. Thanks also to the Special Collections staff and neighborhood partygoers who were unwitting participants in the successful completion of this project.

There are a few people who washed more than one dish: Carla Scaggs, Rebekah Reeves, and Shanna Wilbur. Deirdre doesn't have an automatic dishwasher, but Andrew diduntil this project rendered it useless. We are grateful also to the dedicated readers who helped us fine-tune the manuscript: Carol McGraw, John van Willigen, Marcus McGraw, Rebekah Reeves, and Shanna Wilbur.

Without all of the failed recipes, this project would not have been a success, so we would like to thank the following recipes for making us stronger: White Mountain Cake (the first recipe attempted and horribly failed), Molasses Pie, Vinegar Pie, Apple Fritters, Scalloped Oysters, Butterscotch Pie, Seven Minute Frosting, and Macaroni. A lesson we learned in the process is that you have never really bonded with someone until you have taken turns strenuously beating dough for biscuits for thirty minutesespecially when you mess it up and have to do it all over again.

The many local purveyors must be acknowledged as well: Good Foods Co-op, the Lexington Farmers Market, Weisenberger Mills, and all the local farmers. Resources that we frequently consulted include early American cookbooks, the Joy of Cooking, the Oxford Companion to Food, and our kitchen conversion chart.

We would also like to thank the dean of University of Kentucky Libraries, Terry Birdwhistell, along with all of our friends, family members, colleagues, student assistants, and peers for their support and encouragement throughout this process. We thank the University of Kentucky Libraries for preserving these amazing resources and for allowing use of the photographs and the handwritten recipes.

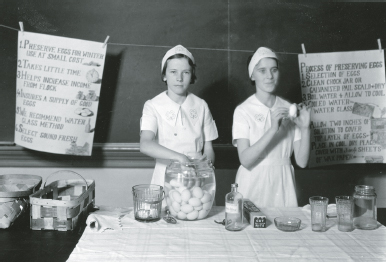

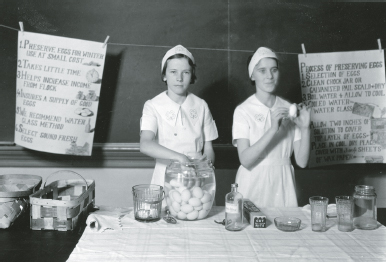

Preserving eggs, circa 1940s. Louis Edward Nollau Nitrate Photographic Print Collection, University of Kentucky Libraries.

Egg and Cheese Dishes

The southern breakfast is symbolic of much that is distinctive and exemplary about food in the South.

John Egerton, Southern Food in History

B ecause cows and chickens were abundant on southern farms, egg, milk, and cheese dishes were enjoyed often at the southern table. Most of the dishes in this chapter are breakfast fare, but the tasty combination also shows up in casseroles, souffls, and sauces throughout southern contemporary and historical cuisine. No one has ruled that an omelet is good only at breakfast, and most certainly the other dishes can be served as main dishes, sides, or desserts. The tomato fricassee was an absolute delight. Although a fricassee is normally made with meat, and typically chicken, this rich gravy has been popular since the colonial era.

Frances Jewell McVey's Meat Souffl, circa 1920s

This dish is light and fluffy. Because the roux is so thick, the meat is distributed evenly throughout the souffl. We used one-half pound of Kentucky ground bison breakfast sausage, but any ground meat would be good. Please note that ground meats such as turkey or chicken would require extra salt.

6 to 8 servings

1 cup ground cooked meat

3 eggs, separated

3 tablespoons butter

3 tablespoons flour

2 tablespoons diced onion

1 teaspoon salt

teaspoon paprika

cup milk

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Brown the meat in an ovenproof skillet over medium heat. Set the meat aside and discard the pan drippings. Beat the egg yolks in a separate bowl. Using an electric or hand mixer, whip the whites until they stand in soft peaks. In the same skillet, over medium to medium-low heat, melt the butter and add the flour. Stir until this mixture is slightly browned; add the onion, salt, and paprika. Stir to combine. Gradually add the milk and cook until smooth and thick, stirring frequently. Add the meat along with the beaten egg yolks and stir until combined. Remove the mixture from the heat and fold in the beaten egg whites gradually. Bake for 30 minutes or until firm and lightly browned. Loosen the edges with a spatula before serving.

Cheese Souffl

Delightfully light and exceptionally creamy, this circa 1920s souffl would make a nice, sweet accompaniment for brunch; it could even serve as a light dessert. This dish is a highly recommended treat that will surprise and impress guests. Once prepared, serve it immediately.

4 servings

cup sour cream

8 ounces Neufchtel cheese

5 tablespoons honey

3 eggs

teaspoon salt

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Heat the sour cream and cheese over low heat stirring until very smooth. Remove the cheese mixture from the heat, add the honey, and mix well. Separate the egg yolks from the whites. Mix the salt into the yolks in a small bowl and set aside. Using an electric or hand mixer, whip the egg whites until they are stiff but not dry. Add the yolks to the cheese and mix to combine. Fold in one-fourth of the egg whites at first to lighten the cheese and egg mixture; then gently fold in the rest. Fill four individual pastry cases or custard cups and bake for 25 minutes.

Scrambled Eggs with Cottage Cheese

These scrambled eggs are as creamy as French omelets: soft, flavorful, and melting in your mouth. The eggs would be terrific served over an English muffin or toast. Allot two eggs per person and adjust the amounts accordingly. The original recipe reads, Neutralize the acid in the cheese with soda and stir into the egg, serve immediately. It did not seem to affect the flavor of the dish, but we followed the instructions faithfully.

2 servings

4 eggs

teaspoon salt or more to taste

Pepper to taste

4 tablespoons milk

teaspoon baking soda

4 rounded tablespoons cottage cheese

Mix the eggs, salt, pepper, and milk. Scramble the mixture in a greased skillet over medium heat. Remove from heat, sprinkle the baking soda over the cottage cheese, and stir into the egg mixture. Serve immediately.