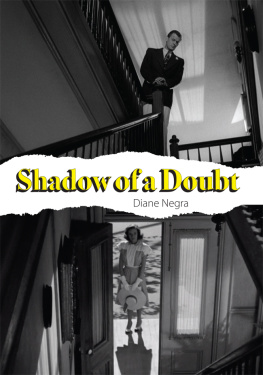

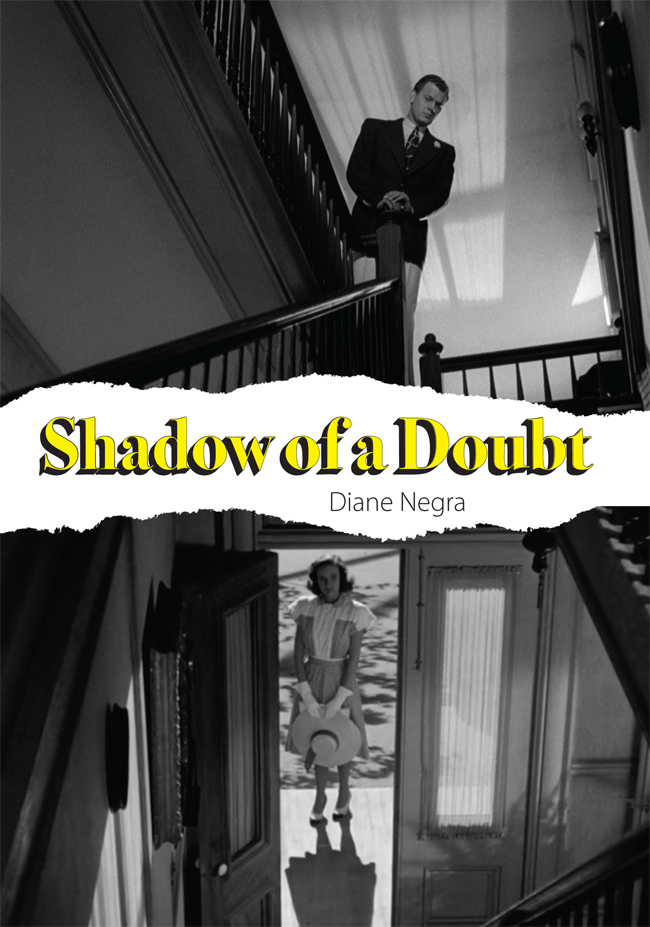

Diane Negras nifty gem of a book is jam-packed with insights into one of Alfred Hitchcocks most underrated (yet among his favorite) movies. Lurking amid the oblique and obvious references to Freud, fascism and foreigners, she finds in Shadow of a Doubt a claustrophobic return to Americas foundational fictionthat it remains an innocent city on a hill, rather than the blood-stained remnant of war and plunder. Negras book, like a reel of film unspooling on the projection room floor, unravels how Hitchcocks obsessions with symmetry and pairing leave the viewer, and in this case, the reader at once informed and anxious. She demonstrates how close reading, archival research and wide-ranging scholarly sources contribute to surprising feminist interpretations of a film that still resonates. Paula Rabinowitz, University of Minnesota

Hitchcocks Shadow of a Doubt, with its idealized portrayal of the American family and rosy depiction of small-town USA, can be easily mistaken for the British filmmakers paean to his adoptive country. In a dazzling close reading of the film, Diane Negra peels off this Rockwellian veneer layer by layer. Her interpretation moves adroitly from Freudian family romance to homefront patriotism, from the female gothic to bourgeois nostalgia, to expose the films dark and intense ambivalences over American consensus culture and family values. In the process, she makes a compelling case for moving Shadow of a Doubt closer to the heart of the Hitchcock canon. Milette Shamir, Tel Aviv University

Diane Negra recognizes and insightfully attends to the characteristically Hitchcockian substrata of metaphysical and existential anxiety and horror in Shadow of a Doubt, and his subtle dramatization of a chaos world without borders. But one of the real contributions of her detailed and finely researched study is her insistence that this dark masterpiece is a harrowing fable of specifically how, to use William Carlos Williamss memorable words, The pure products of America go crazy, directed and overwhelmed by socio-political conditions of our own making. Negra persuasively shows how Uncle Charlies symptomatic monstrosity and Young Charlies complex victimization are intimately related to institutionalized patriarchy and misogyny, stifling family structures, and a culture of smiling evasiveness in the world that they live in: one that is recognizably America in the early 1940s and beyond. Sidney Gottlieb, Sacred Heart University

First published in 2021 by

Auteur, an imprint of

Liverpool University Press,

4 Cambridge Street,

Liverpool

L69 7ZU

Series design: Nikki Hamlett at Cassels Design

Set by Cassels Design, UK

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

All stills from Shadow of a Doubt Universal Pictures.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including

photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to

some other use of this publication) without the permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN paperback: 978-1-80085-931-9

ISBN hardback: 978-1-80085-930-2

ISBN epub: 978-1-80085-810-7

ISBN PDF: 978-1-80085-850-3

Traveling in through a window of a rooming house whose street number is 13, the camera then finds Charles lying on a bed in daytime smoking a cigar, cash scattered on the nightstand and floor beside him. When the landlady enters to tell him that two men called looking for him, he remains impassive and she draws the shade casting the room in darkness before exiting. Charles rises and throws a glass across the room shattering it and signaling to the viewer that the film will engage with Hitchcocks characteristic economy of male anger. Verifying that there are indeed two men on the street outside, Charles exits the rooming house to the strains of melodramatic music but though the pair follow him closely he mysteriously evades them and is next seen peering down at them on the street from a high building. (This is the first surveillant position he takes in the film and he will repeatedly do so again.) In the next scene Charles goes to a telegraph office dictating a communication that reads in part Will arrive Thursday and try and stop me.

We then cut to a low angle shot of a crossing guard and a scene of a pleasant middle-class street in Santa Rosa, California before Hitchcocks camera travels in through a second-floor window of a house on the street to discover a young woman also lying on a bed in daytime. Where we might have expected a contrasting tone the mood here is also dolorous and unsettled; Charlie Newton, a recent high school graduate, speaks bitterly to her father Joe and mother Emma about the dull repetition and meaninglessness of their lives. She is particularly concerned with the limits of Emmas life and the colorlessness she associates with it. It becomes clear even in these early minutes of the film how instrumental Emma is underscoring how her daughters value in the patriarchal order is contingent on her youth and beauty.

As the Newton family re-gather at the end of the day with parents and Charlies young siblings returning home, we glimpse a household in which all members seem to occupy their separate worlds. Importantly, these scenes constitute an early Inspired by the need to redress the torpor and meaninglessness of the familys existence Charlie has a sudden idea that what they need is a visit from her uncle, telling Emma All the time theres been one right person to save us. Although Emma refuses to tell her daughter Charles address, Charlie suddenly recalls it. She then heads to the telegraph office only to discover Charles telegram and walks home in a reverie saying to herself He heard me, he heard me.

Charles meanwhile makes the transcontinental journey in a closed train compartment feigning illness. A group of card players is seated just beside the compartment; among them is Alfred Hitchcock making his signature cameo appearance. Even as it does so, Shadow here emphasizes Charlies pride and pleasure in having authored this scene of reunion; she stands back beaming as the siblings embrace.

Joe shows his brother-in-law to his daughters bedroom (we learn that Charlie had overruled her mother in placing him there) and in a moment of apt wordplay typical of Hitchcocks body of work, tells Charles when he tosses his hat on the bed that he doesnt believe in inviting trouble, as he ushers a man we will come to learn is a serial killer into his home. Charles peers at Charlies high school graduation photo, plucks a rose from a bouquet he finds and uses it as a boutonniere, then tosses his hat jauntily onto the bed. For critics including Gilberto Perez this is a suggestive sequence in a film that is suffused with sexuality.

In the next sequence the Newton family and their guest gather for dinner in the dining room. Charles is holding forth in detail about a yacht he once visited but suddenly interrupts his story to distribute gifts to the group, notably a mink stole for Emma and pictures of their parents that she didnt know hed had, pictures that he tells her hed safeguarded in a deposit box no matter where I was. As the family admire them Charles speaks of the wonderful world of the past in contrast to the world today. Striking a moderate note of disagreement, Charlies effort to argue for the present is belied not only by her characterization of the familys position at the start of the film but also by the particular phrasing of her claim that for once, were all happy at the same time. When Charles prepares to give Charlie her present she demurs and leaves the room.