Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

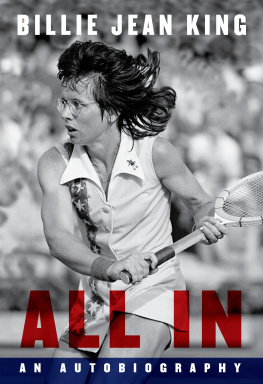

Copyright 2021 by Billie Jean King Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: King, Billie Jean, author. | Howard, Johnette, author. | Vollers, Maryanne, author.

Title: All in : an autobiography / Billie Jean King ; with Johnette Howard and Maryanne Vollers.

Description: New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021. | Includes index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2020055683 (print) | LCCN 2020055684 (ebook) | ISBN 9781101947333 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781101947340 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524712082 (open market)

Subjects: LCSH : King, Billie Jean. | Tennis playersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC GV 994. K 56 A 3 2021 (print) | LCC GV 994. K 56 (ebook) | DDC 796.342092 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055683

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055684

Ebook ISBN9781101947340

Cover photograph by Kathy Willens / AP Images

Cover design by Chip Kidd

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

To Ilana, my love, my partner,

to the moon and back

To my parents,

for their love, laughter, and the values that they instilled

in me that continue to shape my life every day

To my brother, R.J.,

whom I love, for a lifetime of support

and unconditionally loving me back

To everyone who continues to fight for

equity, inclusion, and freedom

Fight for the things that you care about, but do it in a way that will lead others to join you.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Preface

W hen I was a girl Id sit in my elementary school classroom in Long Beach, California, staring at the big pull-down map of the world, and daydream about the places Id go. England, Europe, Asia, South America, Africa! Even then, I felt that borders had no hold on me. They connected me. I cant remember a time when I didnt have a restlessness, an ambition, and an urgency. As much as I loved my family and hometown, I always knew that my life would somehow take me beyond their embrace.

I was born in the wartime 1940s, reared in the buttoned-down 1950s, and came of age during the Cold War and rebellions of the 1960s. My father was a firefighter, and my mother was a homemaker who sometimes sold Tupperware and Avon products to help us get by. They were both determined to give my younger brother, Randy, and me a loving existence that was more stable than their broken families had been. But unrest was all around us. My early life played out against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, the womens movement, the Cold War, assassinations, and antiwar protests of the 1960s; the LGBTQ+ rights movement would come later.

When I began playing youth tennis in the 1950s, college sports scholarships didnt exist for girls. The only womens pro sport was the Ladies Professional Golf Association, which was founded in 1950 by thirteen players but was still working to build purses and gain traction. The modern womens sports movement as we know it essentially started the day nine of us players and a sharp businesswoman named Gladys Heldman, the publisher of World Tennis magazine, broke away in 1970 to create the first womens pro tennis circuit, ignoring the sneers from a male-run tennis establishment that told us no one would pay to see us play, and then repeatedly threatened us with suspensions when it looked as if folks might.

I didnt start out with grievances against the world, but the world certainly seemed to have grievances against girls and women like me: There was the principal who wouldnt sign a permission slip to excuse me for a week-long tennis tournament until my mom went to the school office and said, My daughter is a straight-A student. What could possibly be the problem?; the elementary school teacher who sent a note to my parents explaining that she was marking me down a grade because Billie Jean occasionally takes advantage of her superior ability during recess playground games; the local tennis official at my first tennis tournament, Perry T. Jones, who turned heads by yanking me out of a group photograph when I was eleven years old because I was wearing white shorts, not a white skirt or white tennis dress.

Pursuing your goals as a girl or woman then often meant being pricked and dogged by slights like that. It made no sense to me. Why would anyone set arbitrary limits on another human being? Why were we being treated as unreasonable for asking reasonable questions? Why were we constantly told, Cant do this. Dont do that. Temper your ambition, lower your voice, stay in your place, act less competent than you are. Do as youre told? Why werent a females striving and individual differences seen as life enriching, a source of pride, rather than a problem?

If I felt that way, I wondered how the people of color around me felt. When I was young Id seen photos of how the Little Rock Nine students had to walk past an angry white mob to desegregate their Arkansas school in 1957, and how six-year-old Ruby Nell Bridges still had to be escorted daily by four federal marshals to attend classes at her previously all-white New Orleans school three years later. I knew the stories of how Althea Gibson and Jackie Robinson broke the color barriers in their respective sports, tennis and baseball.

The all-white country clubs that hosted tennis tournaments I began playing in were noticeably different from Long Beachs Polytechnic High, the racially mixed school I attended. Poly was integrated in 1934, nine years before I was born. But my high school didnt offer varsity sports for girls; free tennis instruction in the public parks was my only option.

As time passed, the incidents kept piling up. There was the sight of the top-ranked teenage boys getting free meals at the lunch counter at the Los Angeles Tennis Club while my mother and I sat outside on benches behind the courts, eating the brown-bag lunches we brought. We werent comped, even though I was a top junior player, too. There was the future adviser who introduced himself to me after I won a match at age fifteen and said, Youre going to be No. 1 someday, Billie Jeana thrilling firstonly to have him tell me later, as casually as if he were appraising my backhand, Youll be good because youre ugly.

After I married Larry King and rose to No. 1 in the world, I still faced constant questions about whether playing tennis was worth it, and when I was going to retire and have children.

Do you ask Rod Laver the same questions? Id respond, referring to one of the great male players of my era.

Even if youre not a born activist, life can damn sure make you one.

The older I got, the more I aspired to. There wasnt just unrest in the world around us. There was a storm gathering inside me.

To this day my 1973 Battle of the Sexes match against Bobby Riggs remains cast in the public imagination as the defining moment for me where everything coalesced and some fuse was lit. But in truth, that drive had been smoldering in me since I was a child. What the Riggs match and its fevered buildup proved was that millions of others felt locked in the same tug-of-war over gender roles and equal opportunities. I wanted to show that women deserve equality, and we can perform under pressure and entertain just as well as men. I think the outcome, and the discussions the match provoked, advanced our fight. A crowd of 30,472 , then a record for tennis, came to the Houston Astrodome for the match that September night. An estimated 90 million more watched the event worldwide on TV, a record for a sporting event.