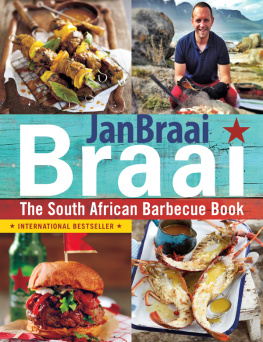

T his book is dedicated to the millions of South Africans who celebrate National Braai Day on 24 September every year.

In National Braai Day, we South Africans have a realistic opportunity to entrench and cement a national day of celebration for our country, within our lifetimes. I believe that having a national day of celebration can play a significant role in nation-building and social cohesion as the observance of our shared heritage can truly bind us together.

In Africa, a fire is the traditional place of gathering. I urge you to get together with your friends and family around a fire on 24 September every year to celebrate our heritage, share stories and pass on traditions. Please help me spread that word!

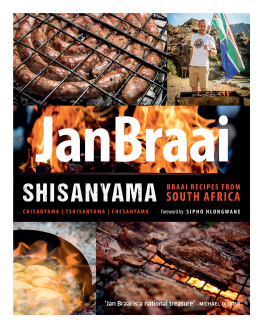

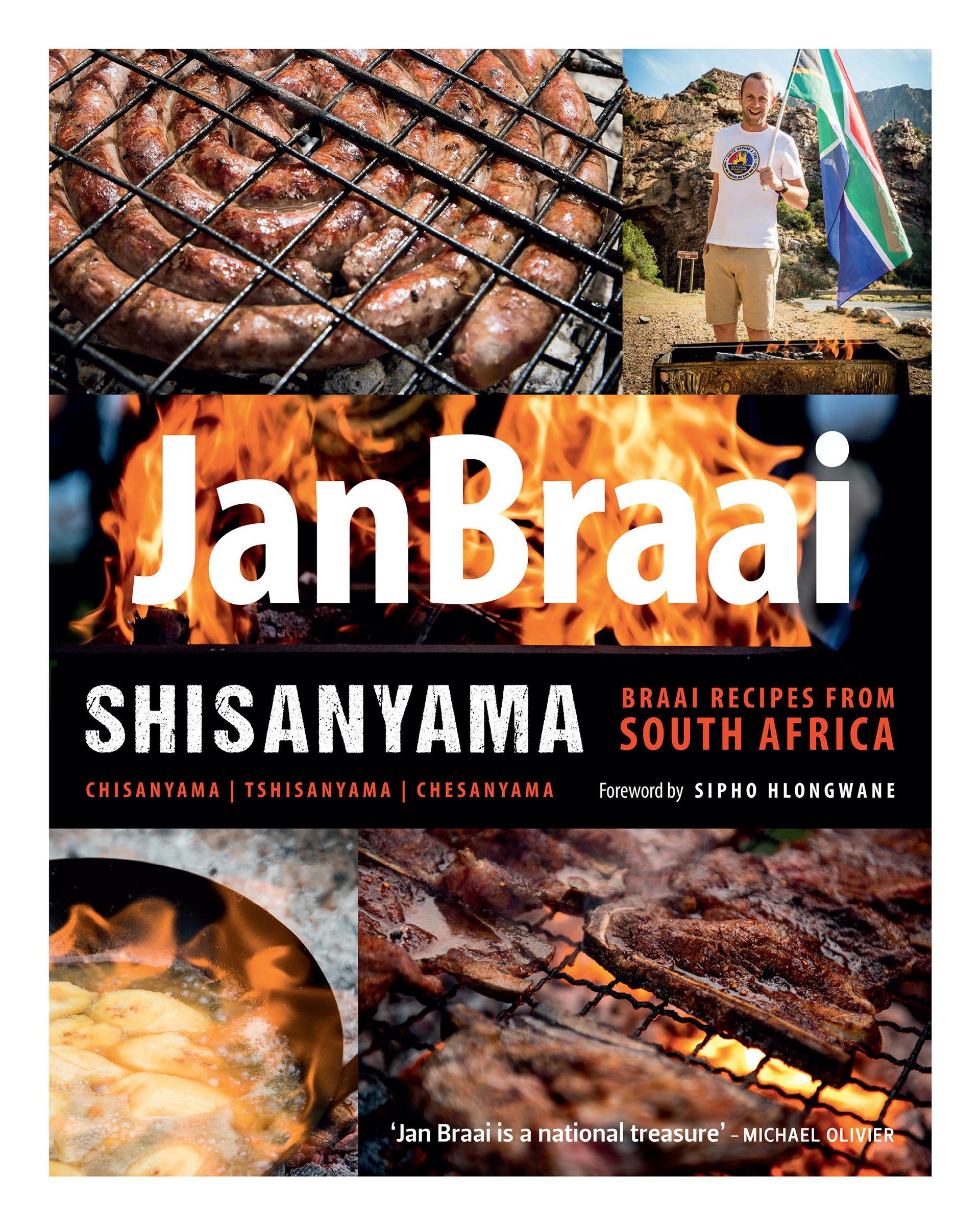

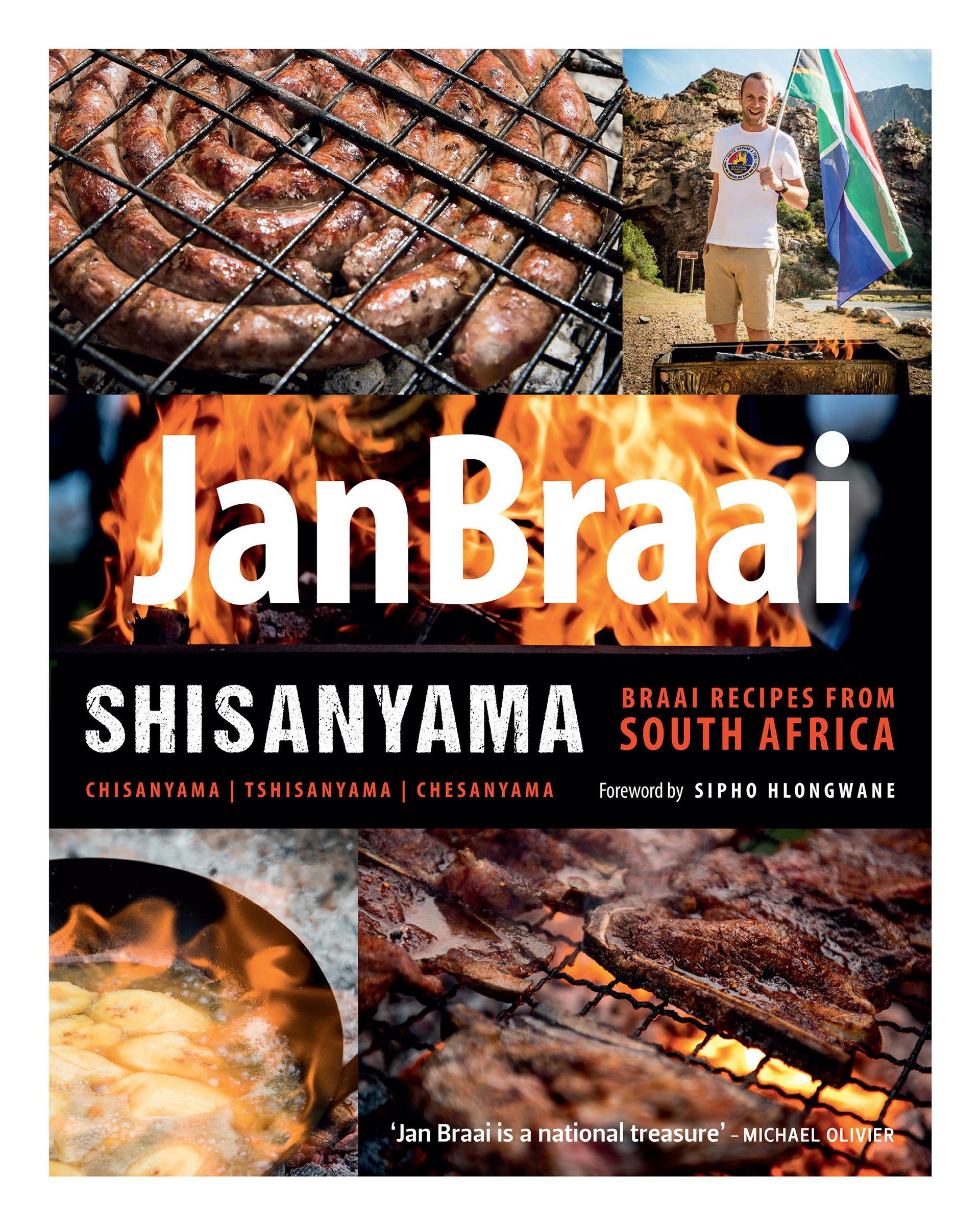

BRAAI RECIPES FROM

SOUTH AFRICA

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

W hen my brother John and I were very young, we would spend our school holidays helping out at the dairy located on the farm where we grew up. It was all terribly exciting. At the beginning of each shift, jumping into the white boots and overalls that were several sizes too large. Learning how to attach the suction cups to a cows teats, and when to pull them off. Finding out how terrible it was to lather the detergent into your eyes accidentally. And the shouts of baleka when one of the cows would lift its tail and send dung splatting all over the milking pit.

But the best part was sitting with the farm hands afterwards, huge wads of bread and cups of milky tea in hand, to listen to them bantering amongst each other. Every once in a while, when one of the cows would be slaughtered, some of the meat would be set aside for the men, and at the end of that day, wed be allowed to join them in the braai.

You have to understand what an extraordinary privilege this was. These were proper Zulu men not your jean-wearing, tsotsi-taal mumbling variants who live in Durban or Gauteng. The real deal. For them to share that kind of a feast with two boys younger than 10 years of age was unheard of. This is why I remember it so vividly.

I learned that these men considered it something special to gather together after a hard days work to feast on braai meat together. They shared stories and jokes, and their hopes and dreams. The meat was apportioned out in a ritual fashion, with the eldest man cutting up the huge hunk of grilled meat and handing it out with a nod and a cheeky comment to each outstretched hand. Each time we brothers got a piece, wed be solemnly told: Thatha-ke, mfana ka Hlongwane!

It has been this way for thousands upon thousands of years in South Africa. Excavations at the Border Cave site in northern KwaZulu-Natal, for example, show that a ceremony, not much different to the one I would partake in, was happening as far back as 35 000 years ago. Back then, they braaied bush pig, zebra, buffalo and warthog. Come to think of it, our meat choices in South Africa havent changed that much at all

Of course, as blue-blooded Zulus, we never called it chisa nyama , ishisanyama or chesa nyama . (The coming together was called ukuwosa inyama .) That came later, when the townships sprang up and brought together people from all over South Africa to produce an altogether new kind of amalgam language that sort of threw everything together: Zulu, Xhosa, Sesotho, Afrikaans, English, and so on.

It doesnt matter what you choose to call it, ultimately. Every South African understands what the significance of the braai is. This is where we come together to gossip, laugh, argue, debate and enjoy each others company. Long may it continue!

Sipho Hlongwane

Johannesburg, 2017

FIRST THINGS FIRST:

THANK YOU, SOUTH AFRICA

T his book is an important piece of braai literature, so please read absolutely everything I say in it with a generous pinch of braai salt. Thank you to everyone who contributed in creating Shisanyama . The book you hold in your hands is a collection of recipes, tips and advice from citizens all across the most beautiful country in the world. Some recipes in this book were not contributed by one person but are the result of many things different people showed, told and taught me over the years, braai-things that then brewed and simmered in my head and led to a certain recipe. Other recipes are a direct result of a public call to the nation to send me their best braai recipes for the creation of this book. Where the bulk of a recipe can be attributed or traced back to a source (or sources), that source is naturally credited.

HOW SHISANYAMA CAME TOGETHER

Thank you to everyone, those credited and anonymous donors, for your generosity in sharing and expanding documented braai knowledge over the years. However, as this book is published under my name, with my name on the cover, I take responsibility for every page of its content. The words in this book were written by me and recipe submissions werent blindly thrown into the manuscript. All recipes in this book, in the format in which they appear, are recipes I can put my name to and feel comfortable to present to the rest of the world.

As such, the process of choosing what to put in the book was harsh, and I had a brutally critical team of colleagues looking over my shoulder. Once it was decided to put a recipe in the book, I took an extremely liberal dose of creative licence to adjust recipes during the writing, testing and editing phases. I do not think there is a single recipe printed here exactly like it was sent to me. Some changes were small, and in these cases the final recipes more or less reflect what was sent to me, with a few tweaks; other changes were large, with my own recipes simply inspired by what Id received. Naturally, I consider all changes made under the all-encompassing creative licence I afforded myself to be for the better but if you disagree, my apologies and I take all the blame.

THE JANBRAAI STAMP OF APPROVAL

There are two important criteria I try apply to all recipes that get the JanBraai name: the recipe is easy, and it just works easy to read, easy to find and measure ingredients, easy to understand the steps, easy to follow the steps, and easy to serve the food; and at the same time, includes the logic of economy. Never use more ingredients just for the sake of it or to sound cool; use measurements that make economic sense, and try to limit dirty dishes. Examples of this would be that I generally wouldnt use soy sauce and Worcestershire sauce in the same recipe, nor lemon juice and vinegar. Broadly speaking, they fulfil the same role, and making you buy both simply to add a spoon of each does not make sense. Neither would I make you add a tin of chopped tomatoes or coconut milk to a potjie. What are you supposed to do with the rest of the tin!?

Next page