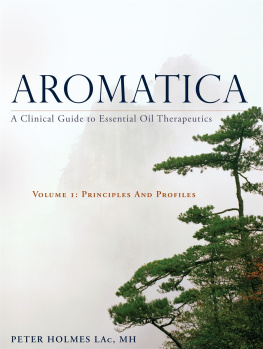

AROMATICA

A Clinical Guide to Essential Oil Therapeutics

V OLUME 2: A PPLICATIONS AND P ROFILES

PETER HOLMES LAc, MH

Contents

1

1

The Clinical Applications of Essential Oils

A S YSTEMIC A PPROACH

This chapter will attempt to do the impossible: to take a systemic approach to the therapeutic uses of essential oils with the full knowledge that the odds against being successful are unfavourable. Their clinical uses have too short a history, their applications are too varied, and the current dichotomy between clinical experience and scientific research is too great. Despite these odds, if we are to make progress to a truly integrated and effective approach to essential oil use, it becomes necessary at this time to scan all the therapeutic knowledge about the oils through the lens of basic clinical criteria. We must ask ourselves some fundamental questions: Do essential oils mainly treat the psyche or the body, or both? What is the relative influence of olfaction and absorption in any effective treatment with essential oils? What are the best forms of delivery and preparation methods for essential oils? What types of illnesses are best treated with essential oils? And what are the best treatment paradigms for the clinical applications of essential oils?

With those exploratory themes in mind, we could certainly do worse than summarize the main types of conditions that essential oils are known so far to address with remarkable success (Chabnes 1838; Gattefoss 1937; Maury 1961; Valnet 1975; Belaiche 1979; Pnoel 1990; Buckle 2003; Price and Price 2007; Franchomme 2015).

Symptom relief. Regardless of the route of administration adopted, essential oils are known to provide good and often rapid relief of signs and symptoms, both acute and chronic pain and fatigue being the most common ones relieved or reduced. The use of essential oils in most delivery forms generally tends to induce a feeling of wellbeing; this may or may not be accompanied by relief of a particular sign or symptom. The main symptoms that are indicated for selecting a particular oil are summarized in the Specific symptomatology sections of this materia aromatica.

The treatment of psychological conditions. Used for olfaction by mild inhalation in their vapour form, essential oils have proven highly effective for treating mental and emotional conditions, including the treatment of mood disorders and various psychological states. These include anxiety, depression, bipolar syndrome, PMS, ADHD and many other such conditions, whether formally diagnosed in Western medicine or not. Any essential oil that evokes a pleasant subjective response in the individual is a good candidate for aromatic therapy by olfaction. This includes oils with many different types of fragrance qualities, ranging from fresh-pungent to sweet-green to floral-sweet. The main symptoms and disorders that are indicated for the psychological use of an oil are summarized in the Psychological sections of this materia aromatica.

The treatment of infections. Since the mid-19th century, if not earlier, essential oils have been applied experimentally and clinically to treating a large variety of infectious conditions. Scientific studies in vivo and in vitro continue to confirm their efficacy, both in their gaseous and liquid phase, in inhibiting the activity and development of most microbes, including bacteria, fungi, viruses and spirochetes. Important oils commonly employed for treating a range of acute and chronic infections of various kinds include Niaouli, Cajeput, Tea tree, Thyme ct. thymol, Oregano, Palmarosa, Clove and Cinnamon. The main infectious conditions indicating use of a particular oil are summarized in the Antimicrobial actions subsections of physiological functions and indications.

The treatment of the general terrain of the individual. Like herbal and homeopathic remedies, essential oils also excel at regulating imbalance of the individual terrain, especially when used over time. In functional and diagnostic terms, this includes a terrain characterized by tension, weakness, heat, cold, dry, damp, and so on. In physiopathological terms, a terrain may be dominated by a particular pathology, e.g. chronic inflammation; congestion; fungal, viral or bacterial dominance; or simply be the result of certain organ or endocrine dominance, such as a hepatic terrain or an oestrogen-dominant terrain. Almost any essential oils may address the whole terrain that underlies specific symptoms, syndromes and disorders. Those least likely to be appropriate for terrain treatment are those with a single dominant fragrance note and chemical constituent, such as Lemon, Cajeput and Wintergreen. Oils for treatment may be given in many different forms of delivery, all depending on individual needs. The main terrain conditions indicating use of a particular oil are given at the start of the sections on physiological functions and indications.

Making Systemic Differentiations among Clinical Applications

Ambiguity and conflation now plague anyone wanting to use essential oils for therapeutic purposes. Essential oils in all their varieties have been commercialized and popularized to the utmost extent of legality, and beyond they have finally entered the cultural mainstream of the Western lifestyle. Healthcare practitioners wishing to embrace the use of essential oils as therapeutic agents clearly need to set themselves apart from popular aroma culture and its profit-driven underpinnings. But herein lies the catch. In order to successfully differentiate themselves, they first need to define themselves through their therapeutic work. The task is mainly about defining clearly and accurately the many ways in which the oils may be put to therapeutic purposes. Practitioners need to clarify their treatment applications before and in order to define themselves.

Terms such as aromatic medicine, clinical aromatherapy, aesthetic aromatherapy and psychoaromatherapy have become increasingly common. Each term purports use in a particular healthcare setting and with particular therapeutic intentions but at best, these definitions are ambiguous and confusing: most imply the exclusive use of oil aroma, despite that not always being the case. As discussed in of the first volume, the problem with these terms is that it is arguably counterproductive today to even use the term aromatherapy, which logically and properly refers to a form of treatment solely based on olfaction and which clearly indicates the therapeutic use of oil aroma alone. Outworn traditional definitions such as aromatherapy and aromatic serve merely to conflate and obscure the true purpose and methodology of different therapeutic applications. Furthermore, these terms erode clarity among practitioners and adherents as regards their own treatment styles and methods. In so doing, they undermine essential oil therapy itself.

It would clearly be more accurate and positive to describe any clinical application of essential oils simply as a particular form of essential oil therapy this is an important issue of terminology. Regardless, however, there is a second problem here: no truly complete and systemic explanation of the ways in which essential oils positively benefit the individual during treatment exists. The oils are extremely and confusingly versatile in their applications in any clinical context. Whether used in their vapour or liquid form, the pathways and processes of absorption and therapeutic effect of essential oils are numerous and polyvalent, and their physiological interactions complex (Buckle 2003; Harris and Harris 2006a; Rhind 2012). It is now well established that there are many means and mechanisms by which essential oils positively influence individual wellbeing and, in a clinical context, treat actual disorders. Most of them are not fully understood.

Next page

1

1