Contents

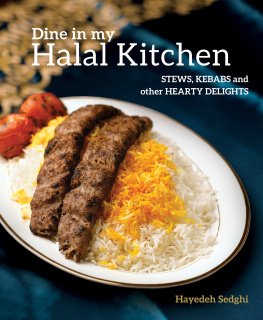

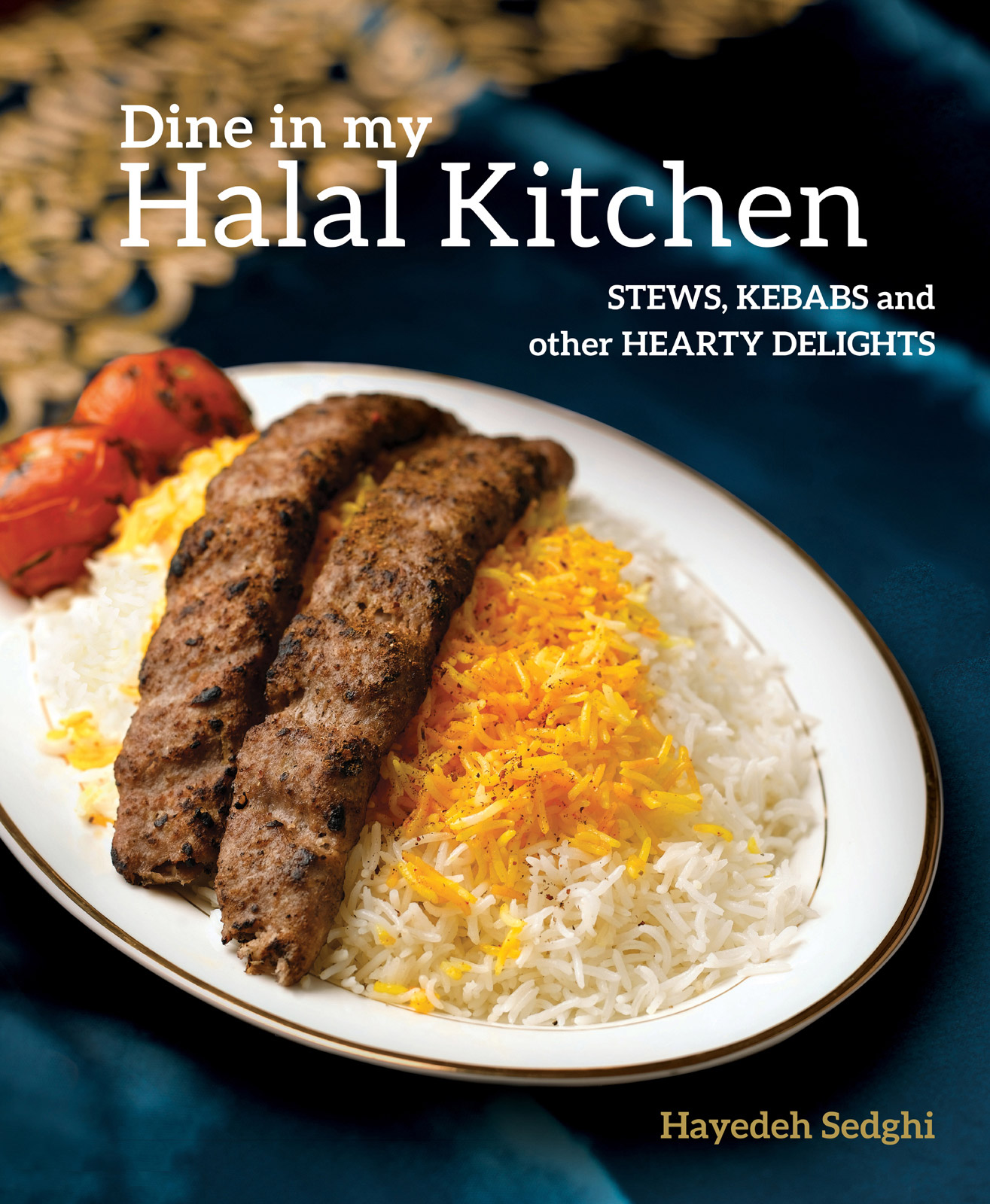

Dine in my Halal Kitchen

Dine in my

Halal Kitchen

STEWS, KEBABS and

other HEARTY DELIGHTS

Hayedeh Sedghi

Contents

Introduction

Iranian cooking can be done using simple cooking utensils, such as medium to

large pots, stew and frying pans, wooden spoons, a masher, and so on. Nothing out

of the ordinary, except for the flat kebab skewers that resemble long swords with

no handles. Nevertheless, there are ways around them. The cooking techniques

are similarly uncomplicated but require time and skills of assessment. Such skills

traditionally come with experience gathered from daily practice, but this book aims

to fast-track the learning process a little for its readers through the use of step-by

step photographs.

Because many of these dishes are characterised by slow-cooking, patience is a

virtue in the kitchen. Be sure you have ample time, at least 2 hours, before deciding

to prepare an Iranian mealtypically consisting of plain rice or a rice dish, a stew or

two and a fresh salad, with yoghurt-based accompaniments and pickles often

on the side. A soup is in order if serving only one stew, otherwise, two stews are

more common.

All recipes in this book make 4 servings if you follow the meal plan above.

Otherwise, any of the rice dishes, excluding plain rice, will easily make a one-dish

meal for 23 people. Although it takes 23 hours to prepare, an Iranian meal is worth

every effort once it is placed on the table or sofreha large rectangular piece of

embroidered cloth that traditional Iranians unfold and lay on the floor at mealtimes,

and diners would sit along the two long sides after the spread of food has been

placed along the centre.

Cooking Techniques

Grilling (Broiling)

The technique of grilling skewered meat, whether lamb, beef or chicken, is an art

form. Getting the kebab right is no mean feat, from how the meat is lovingly kneaded

and marinated to just how brightly the charcoal should glow before it is deemed

worthy for the marinated meat, which will grace the grill for just long enough to

cook through, remain deliciously juicy and become smokily charred in parts. In order

for this to happen, the charcoal has to be very hot and glowing but with few flames.

Iranian kebabs, in particular, are also turned frequently as they cook. Unlike other

styles of barbecuing, a basting liquid is not often used.

Boiling and Simmering

Boiling is common in Middle Eastern cooking, as it is used to cook rice, one of the

staple foods in the region. Rice, like pasta, should only be added to rapidly boiling

water. In Iran, where I grew up, the cooks salt the water that soaks the rice rather

than that in which the rice boils. Parboiled until half-cooked, the rice is then drained

and put into another pot to dry out over low heat until fluffy.

Slow-cooked to draw out the greatest amount of flavour from the ingredients

used, Iranian stews typically feature a type of red meat, which could be lamb or beef;

a mixture of fresh or dried herbs; vegetables such as the much-loved aubergines

(eggplants/brinjals), carrots and potatoes; and pulses such as kidney beans or split

peas. Stews should be always simmered, that means keeping the liquid at a low boil

or barely over the boiling point. The gentle movement of the liquid and its consistent

temperature ensure that the solid ingredients being stewed keep their shape and

become tender, not hard, with prolonged cooking. Cooked in this way, each stew

takes about 2 hours to prepare, but with some planning, two or more stews can be

simmering concurrently.

Pan- and Shallow-frying

Pan-frying is a quick cooking method that is used to prepare certain ingredients for

their inclusion in the main dish. Shallow-frying, on the other hand, is more often

used for preparing light meals, such as Potato and Meat Cutlets (Kotlet). The key

difference between the two methods is the amount of oil used. When pan-frying,

the oil used is just enough to coat the frying surface of the pan in a thin layer,

while shallow-frying means that the oil used should immerse the fried items about

halfway or slightly less. Avoid overcrowding the pan when shallow-frying because

it causes the temperature of the oil to drop suddenly, and when that happens, the

fried items will absorb more oil and become soggy.

Baking

The oven is used for two reasons: first, when a dish needs to be kept warm at low

heat for its flavours to develop and mature, and second: when charcoal grilling is

not available. Fried Aubergine Stew (Khoresh-e Bademjan) illustrates the first point;

because the aubergines and meat are cooked separately, the combined dish is placed

in the oven at very low heat so their flavours can interact and mature. The Baked

Aubergine Dip and Minced Lamb Kebab (Kabab-e Koobideh) recipes in this book are

examples of how the oven is utilised when charcoal heat is unavailable. While there

is far less cleaning up to do when the oven is used, the smoky flavour of the original

dish will be sacrificed.

Pickling

Harking back to the days before refrigeration was available, pickles were made out

of various ingredients to preserve them for the colder months. Usually served on

the side in small bowls, pickles are eaten for a contrast of flavours and to whet the

appetite, much like chutneys and relish. Sometimes, pickles are incorporated into

a dish, such as Chicken Mayonnaise Salad (Salad Olvieh), for example. While some

cooks today still take pride in making their own pickles, most have taken to buying

ready-made ones from delicatessen-like shops or supermarkets. The tray below

contains (clockwise from top right