WISCONSIN LAND AND LIFE

ARNOLD ALANEN

Series Editor

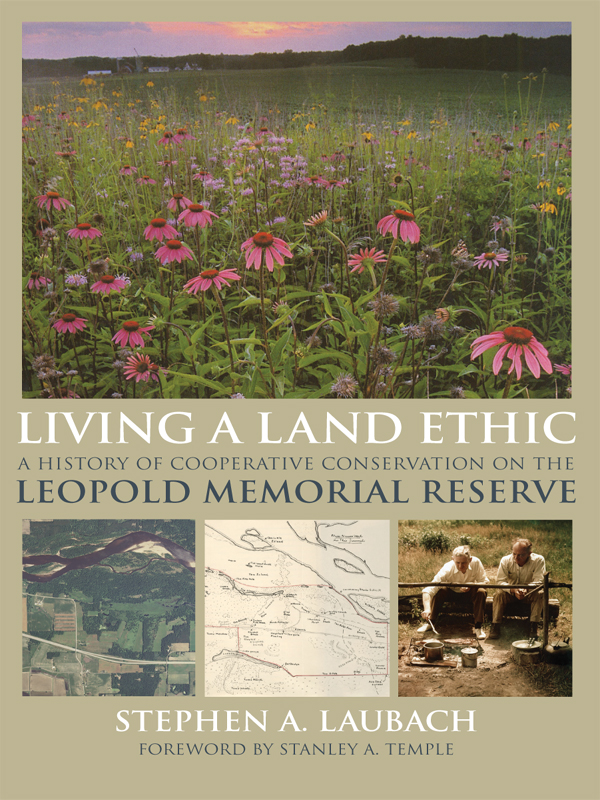

Living a Land Ethic

A History of Cooperative

Conservation on the Leopold

Memorial Reserve

Stephen A. Laubach

The University of Wisconsin Press

This book was made possible, in part, through support from the Lawrenceville School.

A portion of the royalties from this book will be donated to the Aldo Leopold and Sand County Foundations.

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2014

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Laubach, Stephen A., author.

Living a land ethic : a history of cooperative conservation on the Leopold Memorial Reserve / Stephen A. Laubach.

pages cm (Wisconsin land and life)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-299-29874-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-299-29873-9 (e-book)

1. Leopold, Aldo, 18861948. 2. Aldo Leopold Memorial Reserve (Wis.) 3. Natural resources conservation areasWisconsin. 4. Restoration ecologyWisconsin. 5. Conservation biology Wisconsin. I. Title. II. Series: Wisconsin land and life.

S932.W6L38 2014

333.7209775dc23

2013037569

To Nina, Noah, and Aurora

Ecology is the science of communities, and the ecological conscience is therefore the ethics of community life.

Aldo Leopold, The Ecological Conscience, 1947

Contents

Illustrations

Foreword

Stanley A. Temple

As a precocious teenage naturalist I first learned about Aldo Leopolds shack and farm in 1960 when I read A Sand County Almanac. I was captivated by the vivid images in Leopolds month-by-month essays describing his shacks natural surroundings. I knew most of the plants and animals from my rambles around the woods and fields of northern Ohio, but the way Leopold described them was a refreshing change from the matter-of-fact accounts in my field guides. With each essay I imagined what it would be like to experience that landscape firsthand.

My curiosity piqued, I tried in vain to find out more about the place. But like many inquisitive first-time readers, I simply couldnt find Sand County, Wisconsin, in any of the atlases I searched. Somewhat disappointed, I concluded that it must be a fictional place, and the almanac was just a collection of engaging stories Leopold had fabricated. The mystery of Sand County was finally solved when I was a freshman at Cornell and Dan Thompson, who had been one of Leopolds graduate students, was assigned to be my academic advisor. He not only gave me a geography lesson, but he also shared personal recollections of times he had spent at the shack with his mentor. At some point he even mentioned that efforts were underway to protect the land around the shack. I remained curious about the place, but the opportunity to visit and experience firsthand the things Leopold described would have to wait until 1976 when I accepted an offer from the University of Wisconsin to fill the academic position once occupied by Aldo Leopold.

During my first week in Wisconsin my predecessor in Leopolds professorship, Joe Hickey, took me to visit Nina Leopold Bradley and her husband Charlie who had just built their retirement home down the road from the shack. After an emotional pilgrimage to the shack, I spent a wonderful day exploring what I learned had been designated formally as the Leopold Memorial Reserve, the culmination of the efforts Dan Thompson had mentioned a decade earlier. During the day many of the places I remembered reading about came alive, and as a special treat I was even allowed to sleep over at the shack. My new relationship with the land immortalized by Leopolds writings had begun.

Although many natural features of the place were as I had imagined them, I was initially surprised that as far as I could tell the understated Leopold Memorial Reserve amounted to little more than a few property markers. There were no interpretive signs or handouts explaining the significance of the reserve and its purpose, and it seemed the place, which by then was revered by many conservationists, was being kept a carefully guarded secret. I quickly learned there were reasons for the reserves low-key and to some extent even unwelcoming status. The reserve was not a public property but a collection of privately owned parcels, the owners of which had voluntarily agreed to manage their land in ways that would buffer the Leopold shack and farm and exemplify Leopolds land ethic in action. This was a different sort of land conservation project than I was used to encountering on special landscapes.

The personality of the reserve evolved steadily during my years in Wisconsin. Nina and Charlie became the welcoming public faces of the reserve, and the Bradley Study Center where they lived became a focal point for a variety of reserve-related activities. Informal seminars drew loyal Leopold fans, fellowships for students encouraged research on the site, ecological restoration and land management efforts gathered steam, and monitoring projects documented the land and how it was changing. My students and I participated in many of those activities, and as I got to know the parties in the Leopold Memorial Reserve agreement I became increasingly aware of the complex currents and crosscurrents that ran through this special place and the novel agreement that had created it.

This was clearly a fruitful if somewhat fragile conservation success story, as the reserves long-term future was only loosely guaranteed by the original participants voluntary commitments. Since 1976 I have watched this novel experiment in land conservation mature. The influences of individuals and institutions shifted over time, especially as the roles of Reed Coleman and the Sand County Foundation and the Leopold family and the Aldo Leopold Foundation became more prominent when original participants sold their lands to these central players. Evolving visions for the reserve didnt always align, but the reserve quietly endured. Its public visibility expanded again in 2007 when the Aldo Leopold Foundation built its headquarters, the Aldo Leopold Legacy Center, adjacent to the reserve. Public visits to the reserve and interest in it increased rapidly. A series of subsequent land transactions further solidified the central role of the two foundations in determining the reserves future.

Although I had interacted often with the two foundations over the years, I eventually became a more active participant in discussions about the reserves future when I joined the Board of Directors of the Sand County Foundation and became a Senior Fellow of the Aldo Leopold Foundation. As the Leopold Memorial Reserve approached its fiftieth anniversary it became clear to me that the reserves rich but poorly communicated history needed to be documented and shared if the lessons learned there were to be helpful to other land conservation projects. Voluntary land conservation was expanding through the recent emergence of the modern land trust movement, but practitioners knew little about the pioneering efforts to protect Leopolds shack and farm from development through voluntary private action. Fewer and fewer of the individuals who had played significant roles in shaping the reserves first fifty years were still around to share their experiences and insights, and the two foundations, in spite of their differences, needed to find a way to jointly celebrate what had been accomplished. I proposed that a history of the Leopold Memorial Reserve should be written.