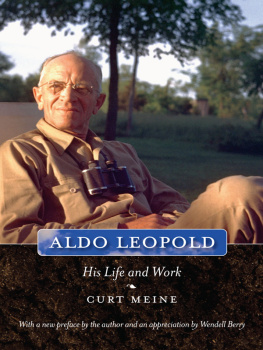

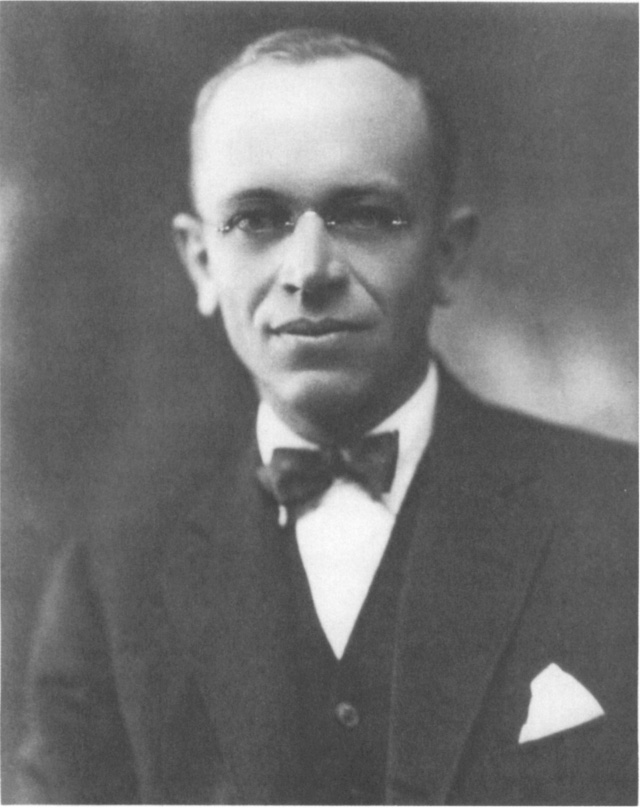

Portrait of Leopold taken shortly after his appointment in 1925 as assistant director of the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin (Leopold Collection, UW Archives)

Aldo Leopold

HIS LIFE AND WORK

Curt Meine

The University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street

London WC2E 8LU, England

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 1988, 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

Appreciation copyright 2010 by Wendell Berry

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews.

5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Meine, Curt

Aldo Leopold: his life and work

Bibliography: pp. 589620

Includes index.

1. Leopold, Aldo, 18871948. 2. Naturalists

WisconsinBiography. I. Title

QH31.L618M45 1987 508.32' 4 [B] 87-40367

ISBN 0-299-11490-2 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-299-24904-5 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-299-24903-8 (e-book)

To my grandparents

Joseph and Helen DeVivo

Whither, midst falling dew

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue Thy solitary way?

William Cullen Bryant

To a Waterfowl

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T. S. Eliot

Little Gidding

Contents

Aldo Leopold: A Readers Testimony

I FIRST read A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold many years agoas time is reckoned by us short-lived humans. By that reading I acquired an influence that would be permanently with me. Leopolds way of looking and his way of thinking have affected my looking and thinking as subtly and persistently as a familial landscape. Although I share Leopolds preoccupation with the land and its fate, I have not had the benefit of his scientific training and discipline, and so knowing I am on his side has given me a measure of assurance I would not otherwise have had. Many others could offer substantially the same testimony.

A Sand County Almanac is not a book to be accompanied by trumpets. It does not try to be overwhelming or sensational. It is a quiet book, and its quietness is that of a man unusually resolved and confident. In the personal essays the writer feels no need to persuade himself or his readers of the authenticity of his pleasures or his worries, and he knows that for involved observers such pleasures and such worries are not extraordinary. The more scholarly or polemical essays are quiet in a different way. They have the tone of responsible discourse, which is necessarily quiet. They are well studied and well argued. Leopold wrote sentence after sentence that goes straight to the core of some problem that is still waiting to be solved. The only significant limitation of those essays is that Leopold could not have imagined the magnitude to which some of the problems have grown after sixty years.

Nobody who has read them needs to be told that the essays in A Sand County Almanac are ably and even beautifully written. There is a level of distinction below which they never dip. But their unique excellence comes from a wholeness that originates in the writer. Their preparation clearly was begun in a responsible life. Even when writing on technical or scientific subjects, Leopold never writes with the assumed dispassion or jargon of the modern specialist. Well-rounded is a term often used as a (customarily frustrated) goal of education; it is often misused in description. Leopold, however, really was well-rounded. In his writing he does not discard any perspective in order to speak from a different one. His sense of humor, which everywhere seasons his thought and steadies his voice, owes much to his awareness of the multiplicity of points of view. It is a part of his sense of responsibility that he writes always as himself. Everything of his that I have read is conditioned by the full extent of his knowledge, his experience, and his concern. When this is not explicit in his words, it is implicit in the shaping and energy of his sentences. We feel his presence in what he says. As much as any writing I know, Leopolds essays require us to recognize character as a literary quality.

Because his writing has, to such an extent, the quality of his character, and because his character was so much that of a conservationist, it is particularly needful that we should know the story of his life. Curt Meine has supplied this need, and he helps us to see clearly how Leopolds writing originated in his life. It is sometimes easy to wonder why we need a biography of a writer. We have none of Homer, almost none of Shakespeare, and it would be a waste of time to wish otherwise. But Leopold was indistinguishably a man of words and a man of deeds, and we see this more clearly in Meines biography than in Leopolds writings.

The sense of completeness in Leopolds life and workhis completeness in himself and his understanding of the original completeness of the natural worldshows us how we are failing. Our bumper-sticker slogans (Think globally, act locally) and our T-shirt vocabulary (sustainable, green, and environment) we seem to have caught from the failure of discourse in politics. I dont know that Leopold would have endorsed, by this time, my own total dislike of the word environmentmaybe in some uses it is pardonablebut it is important to see that in his writing the environment, which has become so witless an abstraction, is characteristically embodied as the land or as places specifically named. And whereas the word environment now seems to take for granted a fundamental difference between ourselves and the world that supposedly environs or surrounds us, Leopold understood carefully that we and the world, the land and its places, are ultimately gathered into a single membership. His understanding of this membership, which he worked out in his life, in his long study of actual places, and in the common cause he made in his life with one actual place, informs at every point the always-responsible discourse of his writing.

My reading of Leopold involves a couple of embarrassments. I did not find and read A Sand County Almanac until I was in my mid-thirties, after I had begun to write of the beauties and troubles of my own home country. If I had read the book earlier, it would have been a much-needed help. My copy is well-worn and cluttered with successive markings in ink and pencil, because I have kept returning to it, as later to other essays, in my continuing need for help. But those returns were intermittent. It was not until I was invited to write this essay that I began a course of reading Leopold, reading about him, and thinking about him and his work every day for several months. My embarrassment, as before, is that I wish I had not waited so long. My preparation for this writing has given me a renewed, and sometimes predictably a new, astonishment at the quality, breadth, and depth of his work. It has also renewed and sharpened my dismay that conservationists and environmentalists have parceled his thinking into halves, one of which they have largely ignored.