THE SECRET LIFE OF WHALES

MICHELINE JENNER is a marine biologist and co-founder of the Centre for Whale Research (Western Australia) Inc. She has studied humpback and blue whales and conducted biodiversity and whale, dolphin and porpoise observation surveys since 1990. With her husband Curt, in 2010 Micheline received a Lowell Thomas Award from The Explorers Club for their work protecting blue whales in the Perth Canyon, Western Australia. Micheline is also a Master Mariner with multiple captains qualifications.

THE SECRET LIFE OF WHALES

MICHELINE JENNER

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Micheline Jenner 2017

First published 2017

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act , no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Jenner, Micheline, author.

Title: The Secret Life of Whales / Micheline Jenner.

ISBN: 9781742235547 (paperback)

9781742244037 (ebook)

9781742248448 (ePDF)

Subjects: Jenner, Micheline.

Marine biologists Australia Anecdotes.

Whales Identification.

Whales Ecology.

Whales Behaviour.

Whales Breeding Western Australia Kimberley Coast.

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Luke Causby, Blue Cork

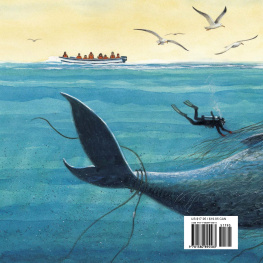

Cover images Wayne Osborn

Illustrations Micheline Jenner

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The author welcomes information in this regard.

CONTENTS

To my dearest mum I dedicate this book.

Among the many things I have to thank you for, I especially appreciate your encouragementto adventure and explore the world.

Thank you.

The whales are absolutely incredible they are so large and yet so graceful, so mellow, so stroppy, so quiet and yet so splashy and loud. Not just a hunk of blubber the size of a bus but a living, moving, thinking creature with order and organisation (even as transient as it may seem to us) and understanding. I give them lots of credit that they know whats going on.

Letter home from Hervey Bay, Queensland, May 1988.

Our task, those of us who care about cetaceans, is to make a place for cetaceans in the sea to ensure what is rightfully theirs and has been for millennia is well protected.

Erich Hoyt, Marine Protected Areas For Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises: A World Handbook for Cetacean Habitat Conservation and Planning , 2005.

INTRODUCTION

I have had the privilege of spending more than half my life living, breathing and thinking about whales. When I first went to Hawaii in 1987, employed on a J1 working visa as a whale researcher at the Pacific Whale Foundation (PWF) in Maui, I pinched myself every day. Fresh out of univer-sity after finishing my Master of Science degree in marine biology at the University of Auckland, I was so excited to wake each morning with the smell of frangipani flowers wafting in from the tropical garden, knowing I was actually living and working in Hawaii. I had gazed at the National Geographic topography map of the Hawaiian Islands on my bedroom wall for most of my childhood and here I was! Moving back to Australia to research humpback whales off the remote north-west coast in 1990 was no less exciting.

My favourite day involves working with whales. After spending 12 hours (or more!) around whales, I love flopping into bed, absolutely dog-tired. As I fall into sleep, the days wonderful sights and sounds fill my dreamy thoughts. I glide through blue water with whales humpback whales, blue whales, dwarf minke whales all different species of whales. The abundance of fresh salty air, warm sunshine, not to mention my arms and legs mildly aching from hours of photography yoga (as I call holding multiple difficult positions for hours while taking photos of whales), all contribute to the thrill of whale research.

In 1987, I met my husband, Curt, a Canadian who was also part of the PWF research team running their intern-ship program in Maui. A year later in a Tahitian lagoon I agreed to Curts wedding proposal; I knew then our life would be one big adventure after another, and so far it really has been.

After we married on a yacht in Maui, surrounded by family and close friends, we volunteered with Ken Balcomb IIIs Orca Survey in the San Juan Islands in the north-west Pacific. Here the seed was sown to begin our own whale research project Down Under. Curt studied the nautical chart of the Western Australian coast and imagined where he would go if he was a humpback whale. The Dampier Archipelago was a similar latitude to the breeding and calving grounds of the Hawaiian Islands, so this seemed a good place to start.

In September 1989 Curt and I wrote to John Bannister (JB, as we affectionately know him), then director of the Western Australian Museum.We said that we were moving to Australia to undertake humpback whale research and would like to work with him. JB checked us out and met with us in Seattle in April 1990. Luckily for us, he decided to support these two blow-ins with enormous logistical assistance and invaluable friendship. Our journey has proceeded together over the last 27 years as we have conducted research collaboratively.Thanks, JB!

On 25 July 1990, we began our research in the Pilbara region. Our base was a research station owned by the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM) on Enderby Island, part of the Dampier Archipelago off the north-west coast of Western Australia. The station, the only shack on this A-class reserve, was used several times a year by staff scientists assessing the rare rock wallaby population. At JBs request, the directors of CALM kindly made the station available to us for five months during winter and spring.

Situated between two beaches on a narrow spinifex-covered isthmus on the eastern end of the island, the research station consisted of a 3-metres by 7-metres cyclone-proof tin shed covered on three sides by a pergola under which we slept, ate and worked. We ran a gener-ator for four to five hours each evening to power lights, two fridges and our computer.The rocky, barren landscape spurred our imagination and we thought we had reached the end-of-the-earth or Enderbyearth!

During that first week in July 1990 we set up camp and ventured offshore in Nova, our 5.3-metre inflatable boat, as often as the weather allowed. On our first few forays we didnt see a single whale. Then, on 5 August 1990, we saw two humpbacks heading directly towards us. I positioned the boat behind and to the side of the pod and measured their pace as Curt balanced in a wind-surfing harness in the bow and began firing off the photographs. We had hardly begun excitedly identifying them (left and right dorsal and fluke photographs) when we spotted another pod of two right behind them. We immediately dubbed the area the humpback highway, and those whales were the beginning of our photo-ID catalogue, which now contains over 4000 whales.

After a couple of seasons in the Dampier Archipelago, we noted that the calves we encountered in this area were four to six to eight weeks old, and thus had to have already been travelling south for a month by whale tail. In JuneJuly 1992 Curt and I spent a month at the Montebello Islands (70 nautical miles to the west of Dampier and 70 nautical miles north of Onslow), where we observed 100 humpback whales travelling on courses between 25 to 30 degrees and heading north-east towards the Kimberley. All roads led to the Kimberley: this was the whales destination and we needed to get there to document this somehow.This discovery led to the construction of our first water-based home, the sailing catamaran

Next page