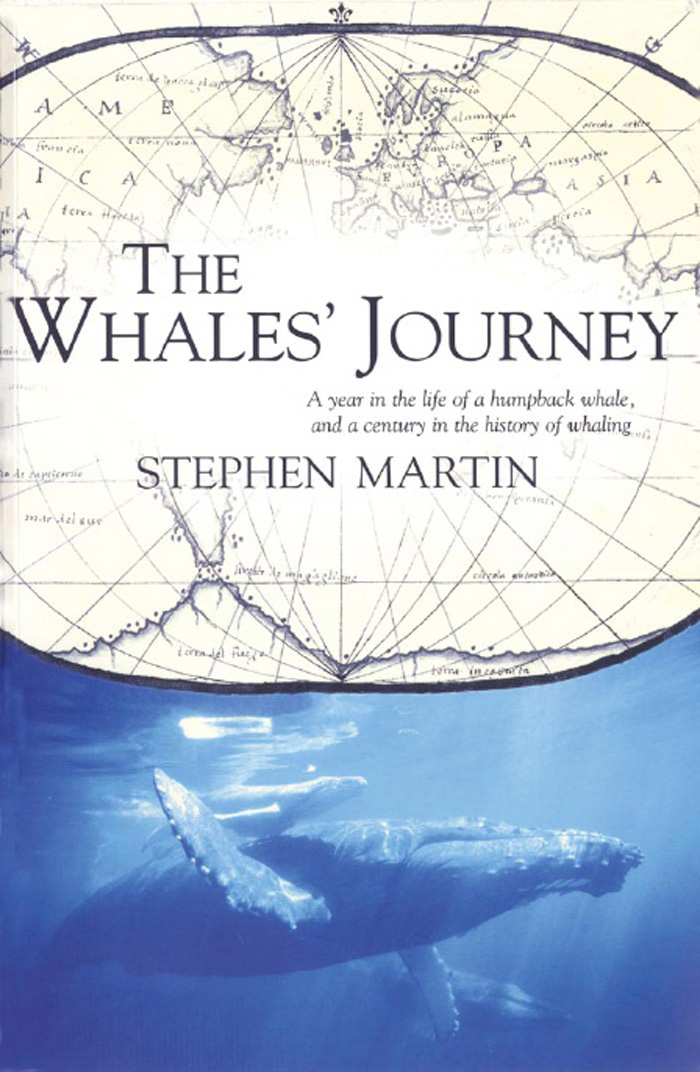

THE

WHALES

JOURNEY

Stephen Martin

First published in 2001

Copyright Stephen Martin 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Martin, Stephen, 1951.

The whales journey.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 978 1 86508 232 5.

eISBN 978 1 74343 222 8

1. Humpback whaleBehaviour. 2. Humpback whaleMigration. 3. Humananimal relationshipsHistory. 4. Wildlife conservationHistory. 5. WhalingHistory.

I. Title.

599.525

Set in 11/15 pt Apollo by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough, Victoria

Contents

A book such as this owes much to many people, and also in this case to two humpback whales, whose ritual dance in the Whitsunday Islands was the beginning point for the research.

At Allen & Unwin, John Iremonger and Ian Bowring added a heroic patience to their initial enthusiasm for the concept. Ians advice was listened to and I hope incorporated into the final work. Ann Crabb pushed the project along and Colette Vella steered the resulting text through to publication. The close and perceptive attention of editor Karen Ward is particularly appreciated.

Cetacean expert Peter Gill answered my many questions and checked the manuscript. Renowned scientist William Dawbin also assisted the project until his death. His family kindly permitted access to his papers and granted permission to publish extracts from his work. The book is richer for their support. Any errors are, of course, mine alone.

Stan Knowles and Eddie May also granted permission to publish extracts from their work.

My colleagues and friends at the State Library of New South Wales were always helpful, steering me towards possible sources of information with unfailing generosity. The staff of other institutions in which I researched were equally supportive.

The support of family members was a source of inspiration, Pic Willoughbys thoughts on whaling regulations were informative. Valerie Thomas and Gabrielle Porteous helped in more ways than they could imagine. My son Tom showed me his whale books and pointed out material on television. My other son Max ate part of the first draft and liked it. As with all my work, the love and comments of Rebecca Thomas were invaluable.

A note on measures

Over the centuries, the unit for measuring volume of whale oil has changed according to nation or period. The measures are left in the text as indications and a guide to the relationships is produced below.

Gallon |

Imperial: | 277.4 in3 = 9.0 lb |

US: | 231.0 in3 = 7.5 lb |

Barrel |

International: | 50 US gal = long ton (approx.) |

US: | 31.5 US gal (except as below)

49.12 US gal (Antarctic and Australian waters) |

Ton |

British or long: | 2240 lb = 298.7 US = 6 bbl |

Metric: | 1000 kg = 2204.6 lb = 293.9 US gal |

Tun

An English liquid measure of seven colonial barrels, each holding about 30 gallons of oil.

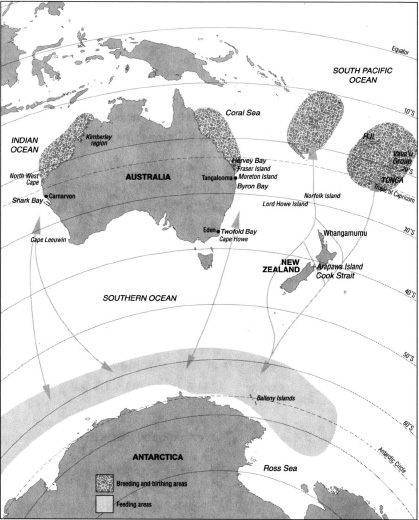

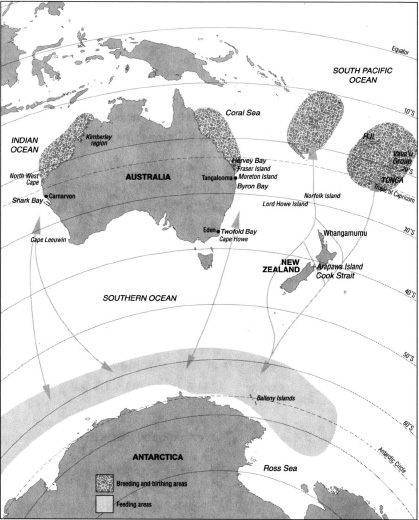

Migration routes of the humpback whales of Australia.

T he story of the humpback whale encompasses many journeys. Once humpbacks were sought out as prey by whalers, who set out in boats and ships into oceans and along the coasts of islands and continents. At the same time, naturalists, and later scientists, pursued a greater understanding of the whale and its behaviour. Their work contributed to the growing and now widely held perception of the whale as a creature deserving protection rather than slaughter. These human journeys, and the changes in their course, can be traced in the most significant humpback journey, the annual migration.

Like many of the great animal migrations, the rhythms and routes of the humpback whales journeys embrace the globe. Prompted by seasonal change, the migration is a pattern of movement to which individuals are behaviourally adapted and physiologically bound. They travel in extended processions of small groups or individuals, swimming through oceanic surface currents and near the coasts of lands that guide their migration. Cliffs, gently sloping beaches, reefs and plumes of silt from rivers and lagoons mark this passage. After several months, as the season turns again the humpback whales begin their return. In this constant and cyclical pattern, humpbacks travel between feeding grounds in the polar regions to birthing and breeding areas in tropical seas.

This book is particularly concerned with the journey of the humpback whales that live in the seas and oceans of Australasia, Antarctica and the South-West Pacific. Although only two of the many humpback populations of the world, they stand as an example of the human impact on the worlds whale populations and for the optimism which now surrounds their recovery from near extinction.

Over the centuries, humpback whales have been seen periodically in many locations within these parts of the Southern Hemisphere. Whaling captain Charles Scammon once described them as having a roving disposition. In the nineteenth century, humpbacks were caught in seas as far apart as the Arafura Sea, just off the southern coast of the island of New Guinea in August and September and the Cook Strait between the two islands of New Zealand, between April and July. By the late nineteenth century, people knew that humpbacks existed near the Balleny Islands off the coast of Antarctica. During the Antarctic exploratory expeditions of the early twentieth century, humpback whales were seen during the southern summer months in the Ross Sea as far south as the Ross Ice Shelf and near the pack-ice edge which stretches out from the Antarctic coast.

These sightings were made before the impact of the twentieth-century slaughter, at a time when humpback whale populations were vigorous and many times larger than today. While researchers know that the limits of humpback roving are indistinct, they also know that the animals may not be as widespread as during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. However, during the last twenty years, humpback whales have been seen in seas off Tonga and close to the Antarctic coast. It may be that the slowly replenishing humpback population is travelling within the broad limits set by their ancestors.