All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142.

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail .

PROLOGUE

This much we know. The first Fin whale to be harpooned in the Antarctic for 30 years was a 19-metre long male.

It was of a species facing a very high risk of extinction and it was killed to the north of Prydz Bay, eastern Antarctica, in a whale sanctuary. It was just big enough to be sexually mature, and close to the upper limi t for handling on a factory ship where it was processed in the name of science.

Some of the death we can piece together. We can see the gunner standing in a slight crouch high on the open bow of the grey chaser. The deck is a-tilt on the Southern Ocean and his feet are apart for balance. His face is hidden from freezing wind blast beneath an earmuffed cap as he stares along a gunsight above the barrel of his cannon. Tracking the whale, he shifts across the deck lightly, like a boxer, swinging the cannon by its handle as he does.

The fast-moving Fin breaks the surface and the gunner squeezes a trigger that looks as harmless as a bicycle handbrake. A grenade-tipped harpoon weighing 45 kilograms blasts out of the cannons muzzle at 113 metres per second and hits an animal that has the mass of a laden semi-trailer. As the blunt-headed weapon drives in, four steel claws are released, a fuse trips, and milliseconds later the grenades high intensity penthrite explodes. The line trailing back from the harpoon to the ship strains, and the barbed claws pull open inside the whale, holding it fast.

We do not know why this particular Fin was chosen. We do not know how long it took to chase the whale down, nor whether it was hit with the first shot. We dont know how many harpoons were needed to kill the whale, nor how long it remained alive. Neither do we know who the gunner was, nor the name of the chaser; how difficult it was to process; where its meat was sold, when, nor for what value.

None of this information went to the organisation that rules on the life and death of whales, the International Whaling Commission (IWC). We do know this was the moment, on 3 February 2006, when the only factory fleet afloat began again to collect the whale meat favoured by some Japanese.

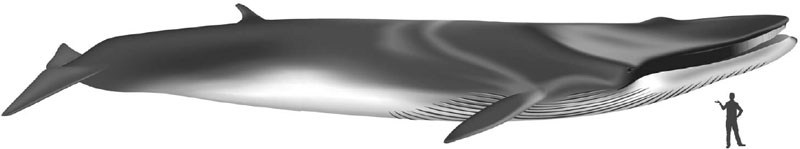

Most things about the Fin whale are unknown to us. They are the secrets of an open ocean whale, rarely seen off populated coasts, which lives in the shadow of the Blue as the second largest animal ever to breathe. It grows up to 27 metres long, can weigh 120 tonnes, and outpace normal ships. We dont see a Fin so much as we see where it has been. The rise and dip of its passage is marked by slick pools that linger on the surface after a high blow puffs in the distance. There went a Fin.

This scale and speed make it a hemisphere cruiser. In the north a radiotagged Fin cantered 2095 kilometres in less than ten days. Fuel for the giant is an overriding need. A 48-tonne Fin, about the size of the 3 February animal, must eat nearly three times its weight in krill over a four-month south polar season to build up enough fat reserves for the remainder of its year.

Organising this banquet needs special skills and Fins have been observed at depth lunge-feeding, taking in tonnes of water and fish at a time. The species also has a unique physical aid: it is asymmetrical. A Fins right side is whiter than the left, and may flash as a contrasting barrier in the water, helping to concentrate swarming prey, ready for the gulp.

In the twentieth century, the era of industrial whaling, more Fins were killed in their Southern Hemisphere stronghold than any other whale species. Nearly three quarters of a million were routed out of the far south, and the last Fins whaled were taken by Soviets in the Pacific off southern Chile in 197576. This is what the adventure of whaling became. Any sense of human daring was fake nostalgia. There was no equality, only the arithmetic of overwhelming mechanical force. The great hunt became the great hurt.

Attempts to heal this deep injury included enactment of the 1986 global moratorium on commercial whaling, and creation of the Southern Ocean Sanctuary for whales, where this Fin swam. Despite these changes, around 28 500 whales since 1986 had been harpooned for sale before this Fin. Whaling was not over, it was growing. Norway and Iceland were raising the number of their kills in the North Atlantic, and Japan was operating at an industrial scale in the Antarctic and North Pacific.

The Fin was Red-listed as endangered by the World Conservation Union, IUCN, but was shot under a scientific permit issued by the Japanese Government, which fabricated a shift in baleen whale dominance in the Antarctic. In the Japanese world, Humpbacks began to outrank Minkes in 199798, and the Fins habitat was expanding. Minkes were thinner and maturing younger under this pressure, according to its fisheries scientists. These changes might even block recovery of Blues. To find out about this phenomenon, whalers had to begin killing Humpbacks and Fins, and oddly, many more Minkes.

Other scientists said between the lines of their critiques that this was shallow artifice, not logical method. Overall whale numbers were a small and threatened fraction of their pre-industrial whaling size. It was plain wrong just to assume that whales competed directly with each other, or that killing Minkes would help Blues. Among other things, seals and seabirds chased the same food. The implacable Japanese whalers set out to kill as many whales every two years as the rest of the world had done in 50 years of scientific whaling. The new kills would move on to Humpbacks, but their techniques would be tried out with Fins.

To reconstruct the fate of these giants it helps to look to Greenland where a few Fins are still taken in an indigenous hunt. From the Green - landers experience we can see how hard it might be to kill the second largest whale ever. In a recent season their exploding harpoons rendered only five of their quota of ten senseless within five minutes. One killing was a harrowing two-hour saga. The initial grenade did not explode. The large, strong, maddened animal broke the line, was chased down and harpooned again with a grenade that blew but failed to kill. Finally the Fin succumbed to a third, grenadeless, harpoon.