Colonialism, Culture, Whales

Environmental Cultures Series

Series Editors:

Greg Garrard, University of British Columbia, Canada

Richard Kerridge, Bath Spa University

Editorial Board:

Frances Bellarsi, Universit Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium

Mandy Bloomfield, Plymouth University, UK

Lily Chen, Shanghai Normal University, China

Christa Grewe-Volpp, University of Mannheim, Germany

Stephanie LeMenager, University of Oregon, USA

Timothy Morton, Rice University, USA

Pablo Mukherjee, University of Warwick, UK

Bloomsburys Environmental Cultures series makes available to students and scholars at all levels the latest cutting-edge research on the diverse ways in which culture has responded to the age of environmental crisis. Publishing ambitious and innovative literary ecocriticism that crosses disciplines, national boundaries, and media, books in the series explore and test the challenges of ecocriticism to conventional forms of cultural study.

Titles available:

Bodies of Water, Astrida Neimanis

Cities and Wetlands, Rod Giblett

Civil Rights and the Environment in African-American Literature, 18951941, John Claborn

Climate Crisis and the 21st-Century British Novel, Astrid Bracke

Colonialism, Culture, Whales, Graham Huggan

Ecocriticism and Italy, Serenella Iovino

Fuel, Heidi C. M. Scott

Literature as Cultural Ecology, Hubert Zapf

Nerd Ecology, Anthony Lioi

The New Nature Writing, Jos Smith

The New Poetics of Climate Change, Matthew Griffiths

This Contentious Storm, Jennifer Mae Hamilton

Forthcoming titles:

Anthropocene Romanticism, Kate Rigby

Cognitive Ecopoetics, Sharon Lattig

Eco-Digital Art, Lisa FitzGerald

Teaching Environmental Writing, Isabel Galleymore

Colonialism, Culture, Whales

The Cetacean Quartet

Graham Huggan

Versions of have previously appeared in the following, slightly modified forms: Last Whales: Eschatology, Extinction, and the Cetacean Imaginary in Winton and Pash, Journal of Commonwealth Literature 52.2 (2017): 382396; Killers: Orcas and Their Followers, Public Culture 29.2 (2017): 287309. Thanks to the publishers for permission to reprint. The author and publisher would also like to thank the following for permission to use the inside images in this book: Cheynes whale by Paul Fearn (p.1) Paul Fearn/Alamy Stock Photo; William Scoresby Arctic Navigator. Date: 17601829 (p.25, left) Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo; William Scoresby Jr by Edwin Cockburn (p.25, right) Bridgeman Images; Tilikum and his trainers at SeaWorld in 2011 by Phelan Ebenhack (p.57) Shutterstock; Scar, the morning of February 9, 2009 by Bryant Austin (p.85) Bryant Austin.

All books, including monographs, are collaborative enterprises. This one would not have been possible without the academic support of the HERA Arctic Encounters team, especially Roger Norum, and, more recently, that of the Environmental Humanities doctoral training network (ITN), whose excellent students should be an inspiration to us all. Many thanks also to Francis OGorman, who patiently read and commented on all of the chapters, and to Greg Garrard and Richard Kerridge for believing in the project in the first place. Finally, life partners are just that with you through thick and thin so the last word must go to Bine, with my love.

Most stories of cruelty have heroic and melancholic versions; and so it is with the history of human encounters with whales. This book opts largely for the melancholic view as a basis for its scattered reflections on whales in the overlapping if non-identical contexts of imperialism, industrial capitalism, and post-industrial corporate power. Whales, after all, are a symbol of guilt as well as an opportunity for atonement, and while they register concern for the future, they also offer painful reminders of a violent past.

One of the premises of the book is that this past is tied up in, though not necessarily reducible to, empire. In the four loosely connected chapters that follow, I will be observing Stephen Howes basic distinction between empires as large-scale political units; imperialism as the actions and attitudes that justify the creation and consolidation of those units; and colonialism as more specific systems of rule by one group over another, where the first claims the right (a right usually established by conquest) to exercise exclusive sovereignty over the second and to shape its destiny (2002: 3031). That whaling was a service industry for empires by no means just the British one is well documented. As Philip Hoare observes, in many ways whales laid the foundations for the British Empire as well as providing the commercial basis for some of the first colonial industries (Hoare 2008). Expanding on this, Richard Ellis notes the close association of whaling with European journeys of discovery and exploration; the formative role of whaling in the early establishment and development of colonies; and the crucial importance of the whaling industry in exporting European and, later, American culture and ideas to the wider world (Ellis 1999; see also Crosby 2009).

This is not to reduce whaling to a mere instrument of empire, in either its economic or cultural forms, but to suggest that it often provided a persuasive rationale for the building of empires (Dodds 2002). As might be deduced from this, it was also at the heart of imperial rivalries played out between the major European maritime powers. More recently, as will be seen, whales have played their part as well in what the Norwegian anthropologist Arne Kalland calls the symbol-politics that has come to surround the global environmental movement a movement in which cetacean conservation has turned into a high-stakes political gambit, a competitive exercise in international relations and corporate lobbying power (Kalland 2009: 193; see also DeSombre 2007, Epstein 2005). This scenario is sometimes seen in terms of the colonial-style discrimination (Sciullo 2008: n.p.) with which powerful Western states have forced whale-hunting bans onto formerly colonized countries, or have lodged bitter protests against aboriginal subsistence whaling, with this last a point to which I will return emphasizing the key role of culture, or perhaps more accurately perceptions of culture, within both whaling and anti-whaling debates.

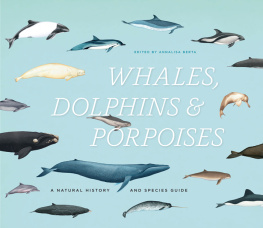

Culture has played a significant role as well in shaping human attitudes towards cetaceans: for, down through the centuries, people the world over have been much more likely to encounter cetacean representations than actual living whales (Kalland 2009). These representations have often organized themselves around specific narratives. As subsequent chapters will show, narratives about whales take many different forms, many of them either explicitly or implicitly allegorical; for whales, whose existence long predates ours, have frequently been associated with mythical stories of human origin as well as apocalyptic presentiments of planetary demise. By no means all of these narratives are sad, but several of them have melancholic tendencies. The story of commercial whaling, in particular, is now almost universally looked upon as one of unrelieved greed and insensitivity. In no other activity has our species practiced such a relentless pursuit of wild animals, and if no whale species has become extinct at the hands of the whalers, it is not for the want of trying (Ellis 1999: x). Whales have literally been torn apart to create oil for lighting, soap, and margarine; baleen and bone for various decorative and sartorial purposes. For a time, the trade in whales for oil would match the trade in humans for sugar as the commercial basis for the British Empire (Hoare 2009: 277); or as a character in Ian McGuires 2016 novel

Next page