Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Copyright 2022 by Tom Mustill

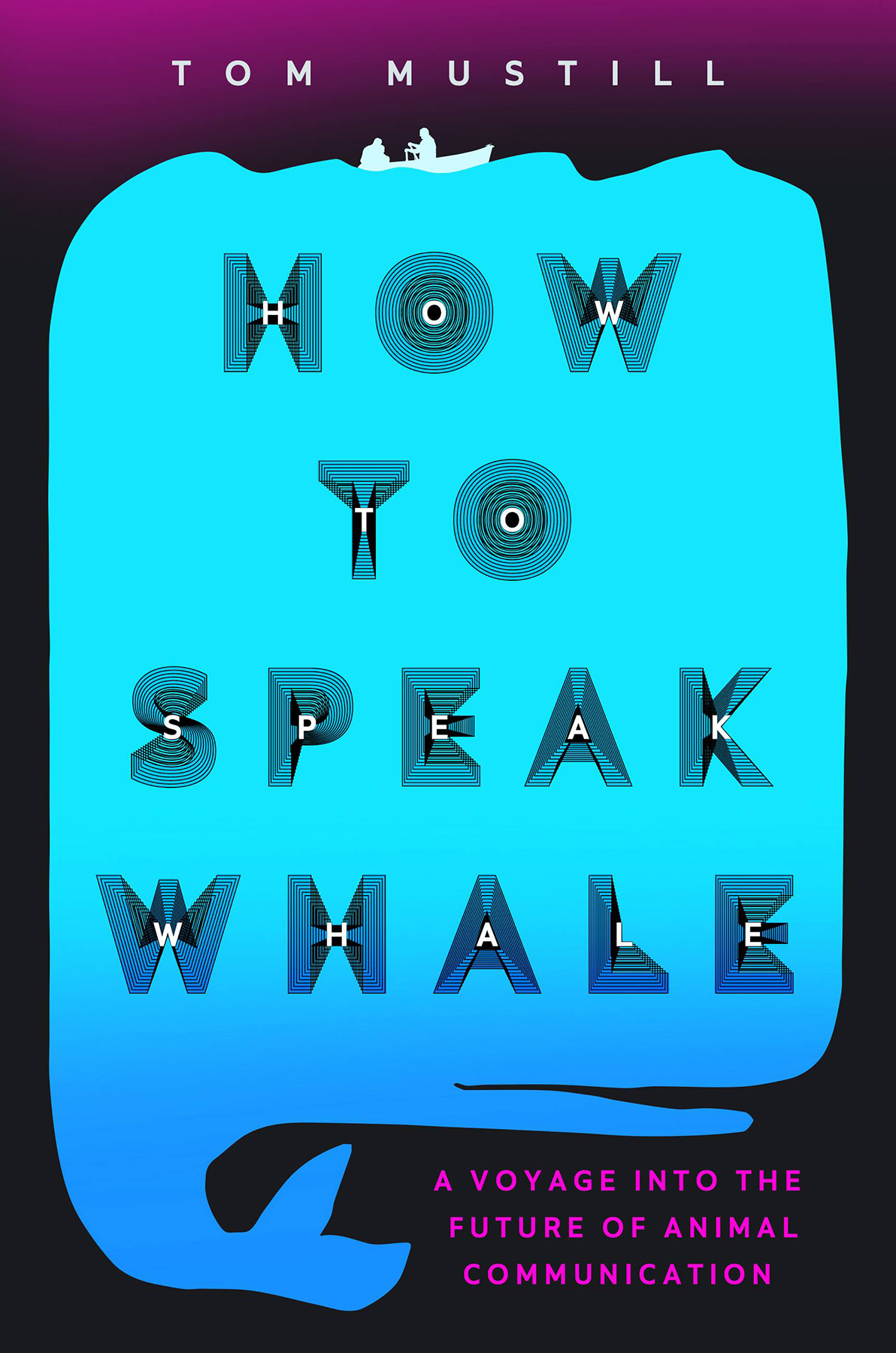

Cover design by Tree Abraham. Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Reading group guide copyright 2022 by Tom Mustill and Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First U.S. Edition: September 2022

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Additional copyright/credits information is .

Scripture quotations marked (KJV) are taken from the King James Version of the Bible.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mustill, Tom, author.

Title: How to speak whale : a voyage into the future of animal communication / Tom Mustill.

Description: First U.S. edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: What if animals and humans could speak to one another? Tom Mustill-the nature documentarian who went viral when a thirty ton humpback whale breached onto his kayak-asks this question in his thrilling investigation into whale science and animal communication. When a whale is in the water, it is like an iceberg: you only see a fraction of it and have no conception of its size. On September 12, 2015, Tom Mustill was paddling in a two-person kayak with a friend, just off the coast of California. It was cold, but idyllic-until a humpback whale breached, landing on top of them, releasing the energy equivalent of forty hand grenades. He was certain he was about to die, but both he and his friend survived miraculously unscathed. In the interviews that followed the incident, Mustill was left with one question: What could this astonishing encounter teach us? Drawing from his experience as a naturalist and wildlife filmmaker, Mustill started investigating human-whale interactions around the world. When he met two tech entrepreneurs, who told him they wanted to use artificial intelligence (AI) to decode animal communication, Mustill embarked on a journey where big data meets big beasts, using animal eavesdropping technologies to train AI-originally designed to translate human languages-to discover patterns in the conversations of animals. There is a revolution taking place in biology, as the technologies weve developed to explore our own languages are turned to nature. From seventeenth-century Dutch inventors, to the whaling industry of the nineteenth century, to the cutting edge of Silicon Valley, How to Speak Whale looks at how scientists and start-ups around the world are decoding animal languages. Whales, with their giant mammalian brains, offer one of the most realistic opportunities for this to happen. But what would the consequences of such human-animal interaction be? Were about to find outProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022019457 | ISBN 9781538739112 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781538739136 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Animal communication.

Classification: LCC QL776 .M88 2022 | DDC 591.59dc23/eng/20220524

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022019457

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-3911-2 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-3913-6 (ebook)

E3-20220816-JV-NF-ORI

For Dad, I wish you could have seen it.

And to Humpback Whale CRC-12564, for setting me on this journey.

How do you expect to communicate with the ocean, when you cant even understand one another?

Stanisaw Lem, Solaris

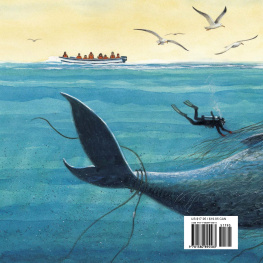

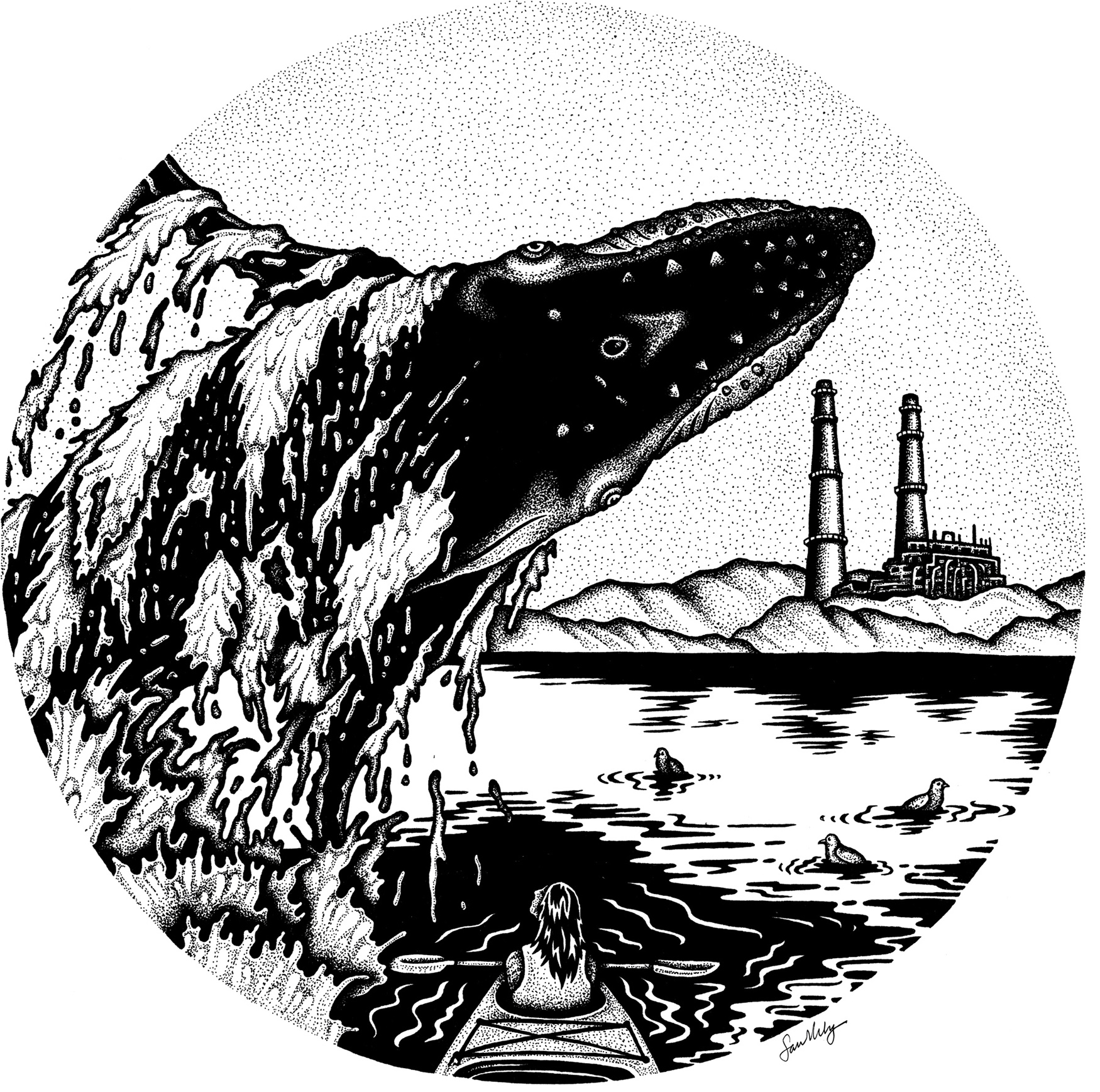

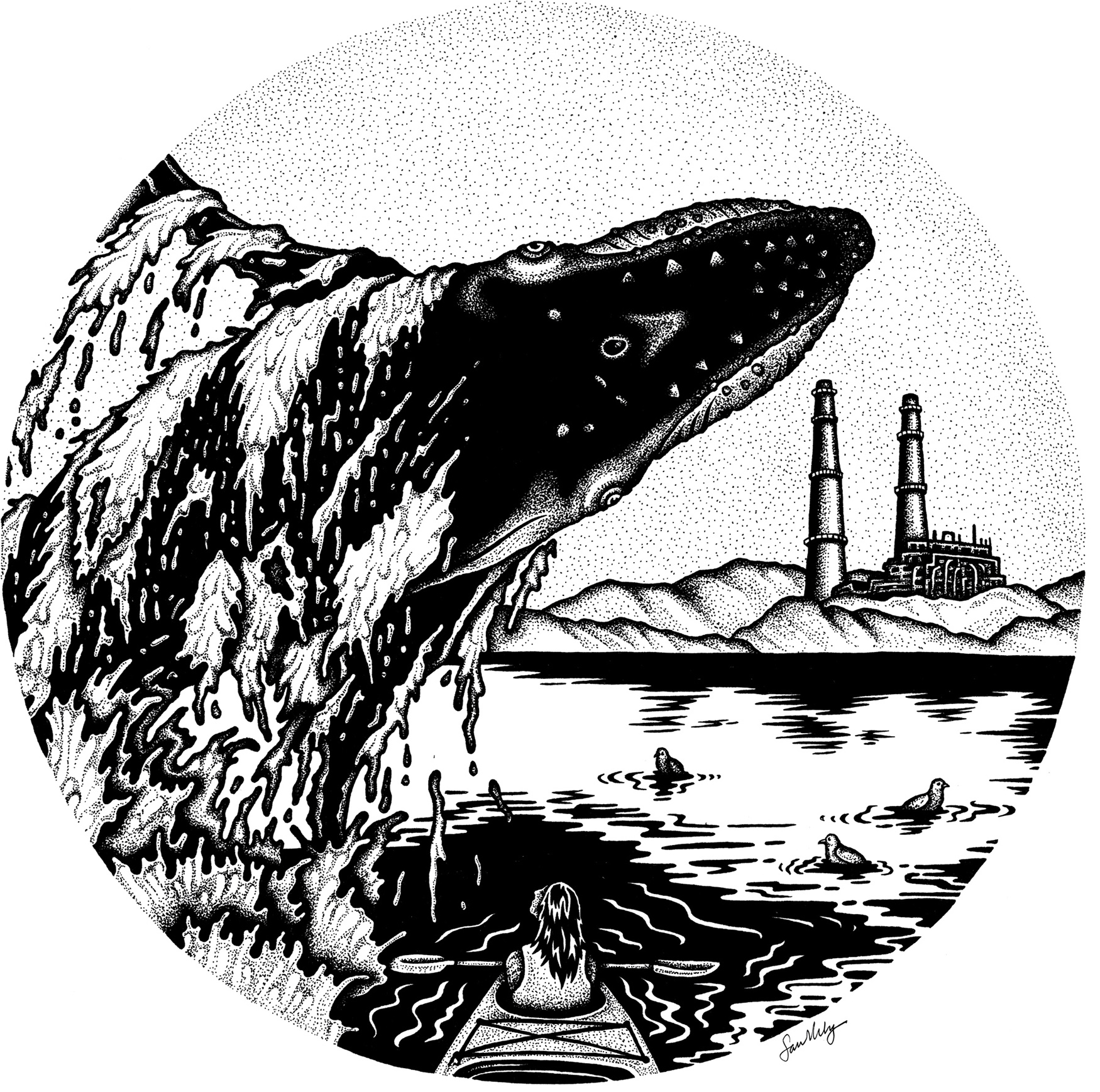

An illustration by the artist Sarah A. King of the view I had as the whale bore down on Charlotte and me.

What if I had never seen this before?

Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder

I n the mid-seventeenth century, in Delft in the Dutch Republic, there lived an unusual man called Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. This is him:

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek holding one of his magnifying inventions in 1686, by Jan Verkolje.

Van Leeuwenhoek was a businessman, a draper. He was also a high-tech inventor. The previous fifty years in Europe had seen the rapid development of tools for magnificationtelescopes and microscopes. Most worked on similar principles, with two glass lenses fitted into a tube. Looking through these lenses gave the user superhuman powers, bringing distant planets and tiny objects into better view. They were also very rare: Few people had learned how to grind, polish, and fit the glasses, and many guarded their secrets closely. For van Leeuwenhoek, as an apprentice draper, microscopes (from the Greek words for small and to look at) were also the tools of his trade, useful for inspecting the quality of the fabrics he bought and sold. The early microscopes could magnify up to nine times, while later iterations could zoom in farther. But the multilens design had a flawthe more they magnified, the more distorted the lenses made the image, and above about twenty times magnification it was hard to make anything out.

In Delft, van Leeuwenhoek had been secretly pioneering a different technique. Instead of using a series of lenses, he became expert at crafting tiny individual spheres of glass, some just over a millimeter in diameter, which he mounted onto folding metal brackets. By placing an object onto the bracket, holding the glass sphere very close to his eye, and looking through it into a source of light, he found he could magnify his subject by up to 275 times and with little distortion. He is thought to have made more than five hundred microscopes during his lifetime. Recent studies have found the focusing capabilities and clarity of his devices comparable to those of modern light microscopes.

Van Leeuwenhoek did not just use his revolutionary magnifying technology to inspect the weave of the cloth he sold. He explored the world beyond his trade. While other microscopists had enlarged and explored the visiblethings like insects, or corkvan Leeuwenhoek discovered entire invisible realms. In a thimbleful of water from a local lake, empty to the naked eye, he was astonished to spy hordes of animalculestiny animals, bacteria, and single-celled organisms. Everywhere he looked, he found scurrying swarms of previously unknown creatures: in the world around usin rainwater and well water, and within our bodiessamples scraped from his mouth and taken from intestines. Van Leeuwenhoek was entranced, writing that no more pleasant sight has yet met my eye than this of so many thousands of living creatures in one small drop of water, all huddling and moving.