Contents

Pages

ANVIL Publishing Inc.

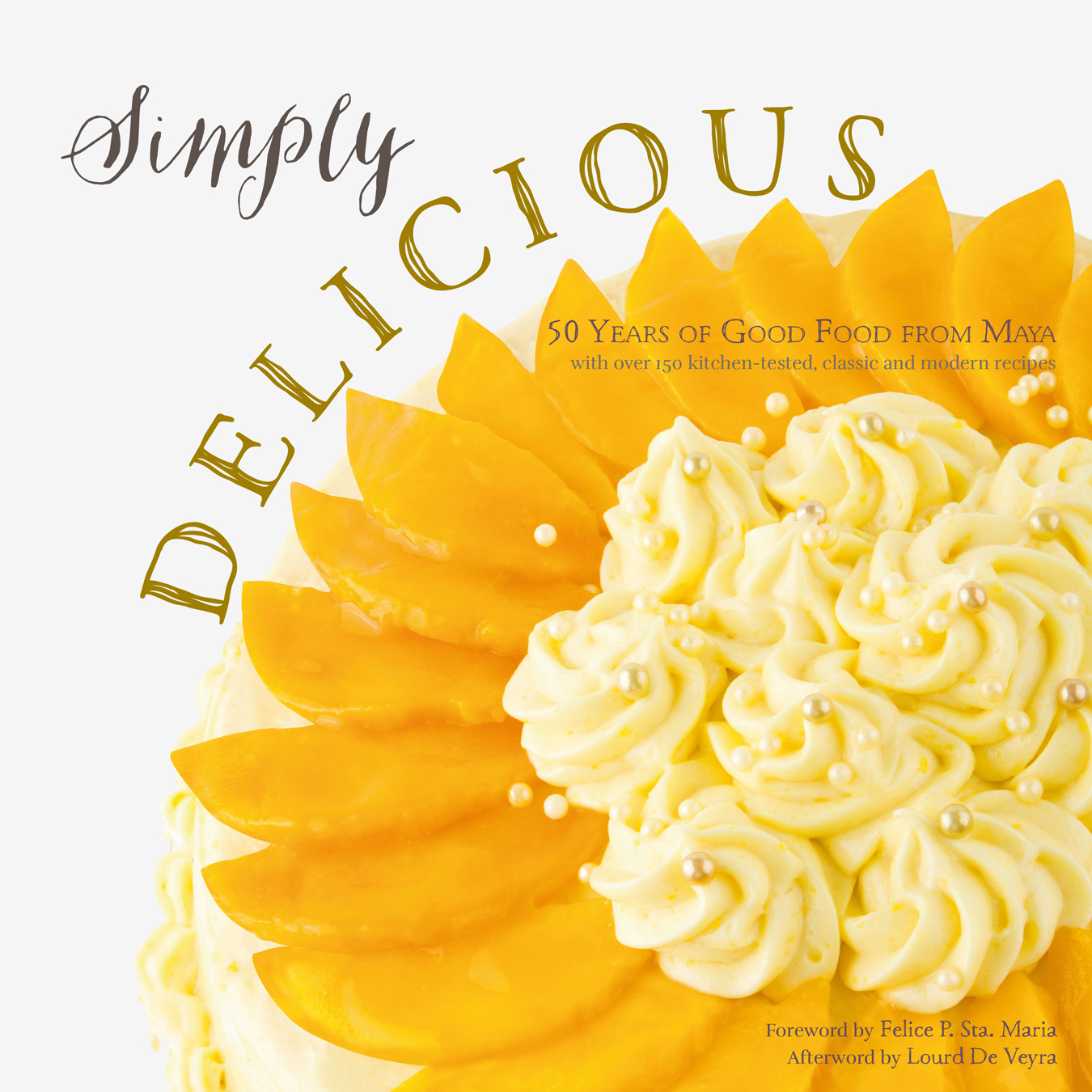

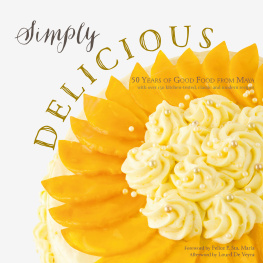

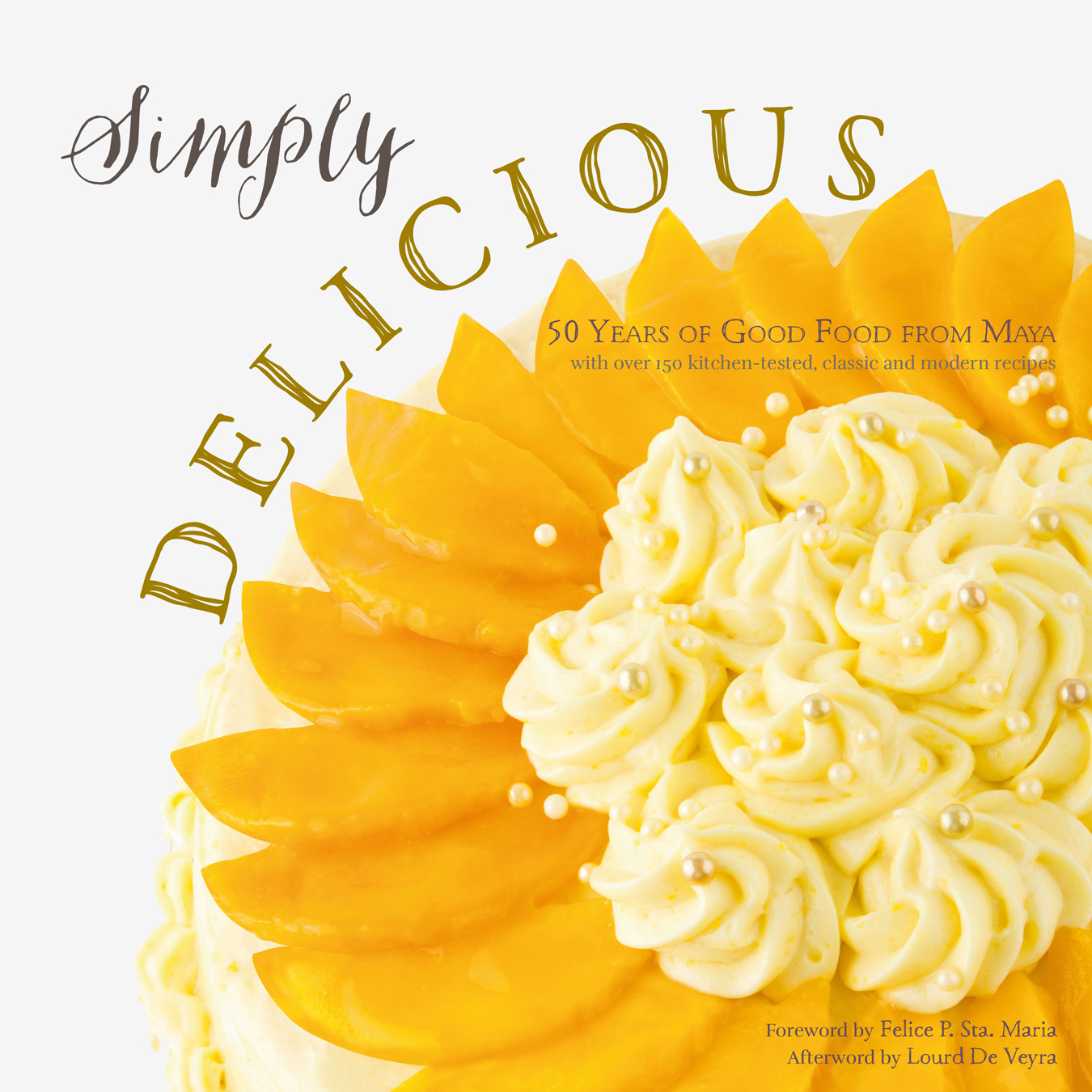

Simply Delicious: 50 Years of Good Food from Maya Copyright Liberty Commodities Corp., 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission from the copyright owner. Published and exclusively distributed by ANVIL PUBLISHING INC. 7th Floor Quad Alpha Centrum 125 Pioneer Street Mandaluyong City 1550 Philippines Telephones: +63 2 4774752, 4774755 to 57 Fax: +63 2 7471622 www.anvilpublishing.com ISBN 978-971-27-3127-3 (e-book) Original text by Joy V. Maalac Recipes edited by Rory C.

Subida Book design by Ige Ramos Photographs by Stanley Ong Food styling by Sandee Masigan Archival photographs provided by Liberty Commodities Corp. The Maya Kitchen Culinary Arts Center 8th Floor Liberty Building, Arnaiz Avenue, Makati City Telephones: +63 2 8921185 and 8925011

Baked savories and sweets share an attractive story. The litany of Philippine culinary attractions ranges from the everyday pan de sal bread to the divine sans rival cake. One cannot imagine Filipino fare without them today. While roasting, boiling, and frying assure a treasury of delights, the introduction of baking to cooking procedures increases the potential for using available ingredients in innovative, valuable, and seductive ways. The Horno Still to be dated unquestionably is when foods first were cooked locally buried in hot ash still glowing with embers.

Baked savories and sweets share an attractive story. The litany of Philippine culinary attractions ranges from the everyday pan de sal bread to the divine sans rival cake. One cannot imagine Filipino fare without them today. While roasting, boiling, and frying assure a treasury of delights, the introduction of baking to cooking procedures increases the potential for using available ingredients in innovative, valuable, and seductive ways. The Horno Still to be dated unquestionably is when foods first were cooked locally buried in hot ash still glowing with embers.

In northern Philippines, two rice cakes baked in that manner are famous. Sinibaludocumented in the 1930s as the Longest Christmas Cake in the World measuring two feet to a meter in lengthis made in the Cagayan River area. A batter of glutinous rice, coconut milk, and a sweetener is stuffed into a green coconut culm having a diameter of two to three inches; banana leaves seal the open end during baking. Made similarly is comforting tupig in Ilocos. Rice flour, coconut milk, and sugar are by Felice Prudente Sta. Maria W o r t h y E n d e a r m e n t Foreword  rolled into small cylinders wrapped in layers of banana leaf then baked in hot ash or an oven.

rolled into small cylinders wrapped in layers of banana leaf then baked in hot ash or an oven.

Across most of the archipelago, the oven is named from the Spanish word for it: horno. In 1754, horno was not yet on Tagalog word lists; apogan was used to mean an horno de cal for making lime used in betel nut chew. But Tagalog used the verb huhurnuhin in recipe books at the start of the twentieth century. The Spanish oven introduced was much like those on the Iberian Peninsula that resembled a small, thick-walled stone or brick cave. The first Spanish immigrants arrived in 1565 led Miguel Lopez de Legaspi. They missed their daily bread and had difficulty adjusting to rice.

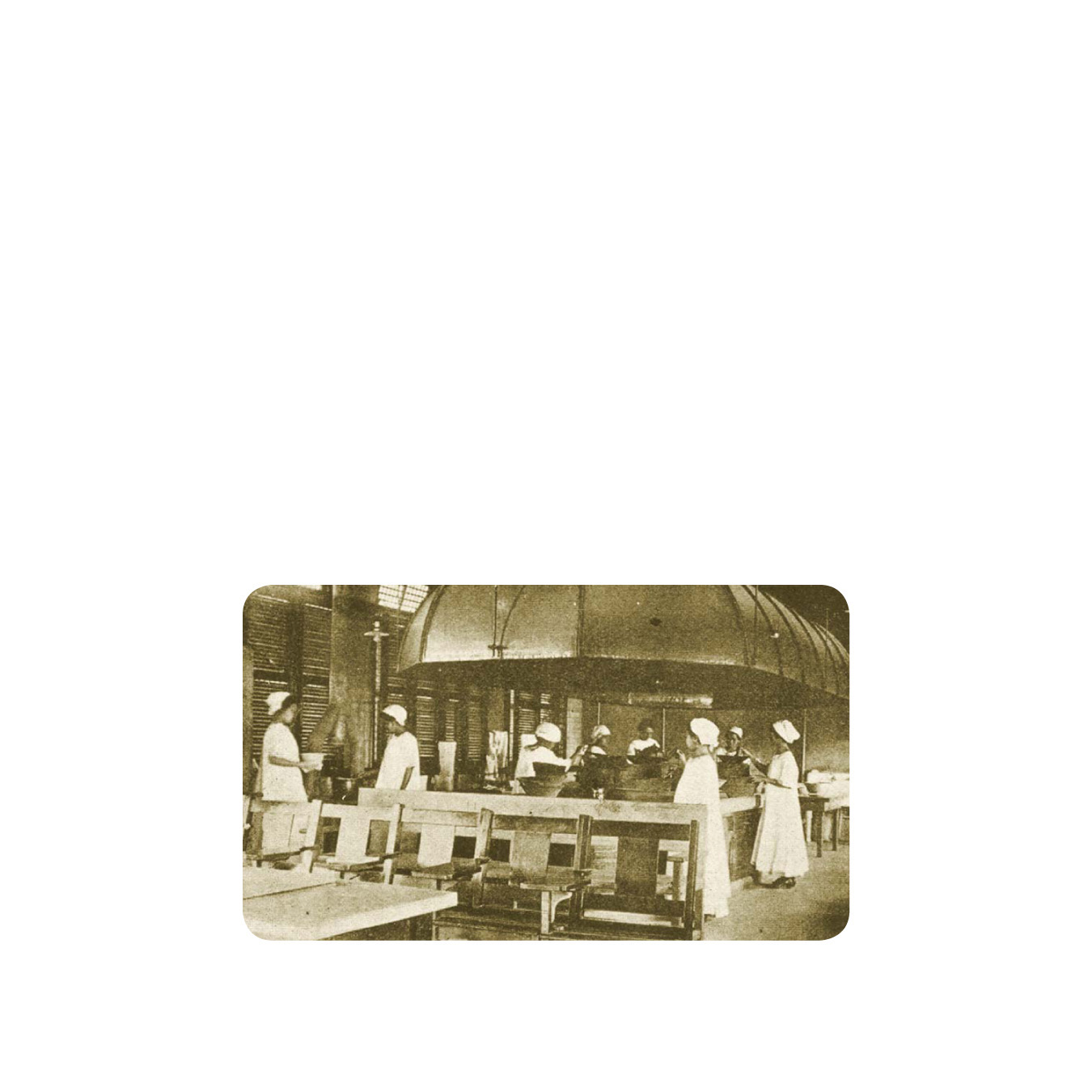

Once Manila was organized as the colonial capital, migrant Chinese baked bread in their nearby enclave. Records show that in 1625, Philippine Governor-General Fernando de Silva permitted only one bakery for security. But Spanish professional bakers preferred to reap profit from the galleon trade rather than practice their career, so Chinese staffed the sweltering royal bakery inside Intramuros. Domestic science class in Philippine Normal School  The Panaderia In 1576, the Council of Milan ordered that only the religious could make altar bread. Although tinapay is a generic Filipino name for bread today, in 1521 during the first circumnavigation, the word meant a particular circular rice cake with a sweet filling. Because missionaries used tinapay as the word for wheat bread when explaining biblical stories and in Pater Noster translations, tinapay acquired a new definition and wheat was introduced into the country for religious and secular needs.

The Panaderia In 1576, the Council of Milan ordered that only the religious could make altar bread. Although tinapay is a generic Filipino name for bread today, in 1521 during the first circumnavigation, the word meant a particular circular rice cake with a sweet filling. Because missionaries used tinapay as the word for wheat bread when explaining biblical stories and in Pater Noster translations, tinapay acquired a new definition and wheat was introduced into the country for religious and secular needs.

The price of a bread bun, the panecillo, was comparatively expensive and matched the cost of three cups of second-class brown rice in 1875. However, the popularity of bread in Manila and its environs was on the rise. There were around ten bakeries into the revolutionary era of the 1890s listed in tour guides and official city business rosters. Bakeries continued spreading to prosperous centers on the islands. Philippine breads used salt, milk, pork fat, local alcoholic beverages, eggs, sugar, and baking powders to vary texture and taste. A panaderia or bakery could also sell bizcocho and sopas, two popular cookie-like products eaten with chocolate, the common beverage of choice in those days.

The Dulceria The variety of baked goods increased considerably after the Suez Canal opened in 1879, shortening Europe-Philippine travel time to about a month. Not only did Manila have panaderia but also dulceria to sell dulce, sweet continental confectionary, and artisanal bakers bringing ingredients like butter in newly invented tin cans and, as years went by, equipment to increase production and decrease product prices. Travelers to Filipinas complemented locally made flaky pastry. Its recipes may have been those in what seem to be the earliest Philippine printed cookbooks. Along with procedures for making gulay, lumpia, pacsiu  de pescado, and pansit, in La Cocina Filipina (1913) are recipes for baked empanada de carne en horno using marinated meat, garlic and tomato; pavoasado en horno; pastel de los libras; pastel made with meat, clove, cinnamon, cumin, and red pimienta ; empanada de pescado flavored with saffron and orange flower oil; empanaditas de lasmonjas de Medina steeped in clear syrup then left to dry; torta de almendras y avellanas; cajitas de almendras de Medina; merengues; hojaldres; tortas de moron using pork lard; rosquillas ; and bizcochos. Condimentos Indigenas (1918) by Pura Villanueva de Kalaw did not include anything oven-baked among her common fare.

de pescado, and pansit, in La Cocina Filipina (1913) are recipes for baked empanada de carne en horno using marinated meat, garlic and tomato; pavoasado en horno; pastel de los libras; pastel made with meat, clove, cinnamon, cumin, and red pimienta ; empanada de pescado flavored with saffron and orange flower oil; empanaditas de lasmonjas de Medina steeped in clear syrup then left to dry; torta de almendras y avellanas; cajitas de almendras de Medina; merengues; hojaldres; tortas de moron using pork lard; rosquillas ; and bizcochos. Condimentos Indigenas (1918) by Pura Villanueva de Kalaw did not include anything oven-baked among her common fare.

Her postre were fried, steamed, or air-cooled after simmering. The following year, Rosendo Ignacio translated European recipes into Tagalog and added them to Filipino ones. He included mamonescon mantequillado; mamongrande; tartaletes; tartaletes de vainilla; pan de viena; pan de leche; timbal de patatas; bicocho; biscochos de fraile; rosquillas kissed with white wine and anise; hojaldres de sebo; pastel casero filled with laurel-spiced beef; and pastel caliente. His selection may be an indication of what families at the time desired on their tables. The last official Spanish feastone that prematurely celebrated the end of the Philippine revolution in February 1898was catered by Restaurant y Dulceria de Paris on Escolta. On the menu were assorted pastries.

Next page

ANVIL Publishing Inc.

ANVIL Publishing Inc.  Simply Delicious: 50 Years of Good Food from Maya Copyright Liberty Commodities Corp., 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission from the copyright owner. Published and exclusively distributed by ANVIL PUBLISHING INC. 7th Floor Quad Alpha Centrum 125 Pioneer Street Mandaluyong City 1550 Philippines Telephones: +63 2 4774752, 4774755 to 57 Fax: +63 2 7471622 www.anvilpublishing.com ISBN 978-971-27-3127-3 (e-book) Original text by Joy V. Maalac Recipes edited by Rory C.

Simply Delicious: 50 Years of Good Food from Maya Copyright Liberty Commodities Corp., 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the written permission from the copyright owner. Published and exclusively distributed by ANVIL PUBLISHING INC. 7th Floor Quad Alpha Centrum 125 Pioneer Street Mandaluyong City 1550 Philippines Telephones: +63 2 4774752, 4774755 to 57 Fax: +63 2 7471622 www.anvilpublishing.com ISBN 978-971-27-3127-3 (e-book) Original text by Joy V. Maalac Recipes edited by Rory C.

Baked savories and sweets share an attractive story. The litany of Philippine culinary attractions ranges from the everyday pan de sal bread to the divine sans rival cake. One cannot imagine Filipino fare without them today. While roasting, boiling, and frying assure a treasury of delights, the introduction of baking to cooking procedures increases the potential for using available ingredients in innovative, valuable, and seductive ways. The Horno Still to be dated unquestionably is when foods first were cooked locally buried in hot ash still glowing with embers.

Baked savories and sweets share an attractive story. The litany of Philippine culinary attractions ranges from the everyday pan de sal bread to the divine sans rival cake. One cannot imagine Filipino fare without them today. While roasting, boiling, and frying assure a treasury of delights, the introduction of baking to cooking procedures increases the potential for using available ingredients in innovative, valuable, and seductive ways. The Horno Still to be dated unquestionably is when foods first were cooked locally buried in hot ash still glowing with embers. rolled into small cylinders wrapped in layers of banana leaf then baked in hot ash or an oven.

rolled into small cylinders wrapped in layers of banana leaf then baked in hot ash or an oven. The Panaderia In 1576, the Council of Milan ordered that only the religious could make altar bread. Although tinapay is a generic Filipino name for bread today, in 1521 during the first circumnavigation, the word meant a particular circular rice cake with a sweet filling. Because missionaries used tinapay as the word for wheat bread when explaining biblical stories and in Pater Noster translations, tinapay acquired a new definition and wheat was introduced into the country for religious and secular needs.

The Panaderia In 1576, the Council of Milan ordered that only the religious could make altar bread. Although tinapay is a generic Filipino name for bread today, in 1521 during the first circumnavigation, the word meant a particular circular rice cake with a sweet filling. Because missionaries used tinapay as the word for wheat bread when explaining biblical stories and in Pater Noster translations, tinapay acquired a new definition and wheat was introduced into the country for religious and secular needs. de pescado, and pansit, in La Cocina Filipina (1913) are recipes for baked empanada de carne en horno using marinated meat, garlic and tomato; pavoasado en horno; pastel de los libras; pastel made with meat, clove, cinnamon, cumin, and red pimienta ; empanada de pescado flavored with saffron and orange flower oil; empanaditas de lasmonjas de Medina steeped in clear syrup then left to dry; torta de almendras y avellanas; cajitas de almendras de Medina; merengues; hojaldres; tortas de moron using pork lard; rosquillas ; and bizcochos. Condimentos Indigenas (1918) by Pura Villanueva de Kalaw did not include anything oven-baked among her common fare.

de pescado, and pansit, in La Cocina Filipina (1913) are recipes for baked empanada de carne en horno using marinated meat, garlic and tomato; pavoasado en horno; pastel de los libras; pastel made with meat, clove, cinnamon, cumin, and red pimienta ; empanada de pescado flavored with saffron and orange flower oil; empanaditas de lasmonjas de Medina steeped in clear syrup then left to dry; torta de almendras y avellanas; cajitas de almendras de Medina; merengues; hojaldres; tortas de moron using pork lard; rosquillas ; and bizcochos. Condimentos Indigenas (1918) by Pura Villanueva de Kalaw did not include anything oven-baked among her common fare.