Table of Contents

About the Author ix About the Technical Reviewer xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction xv Preface: Document Conventions xvii

Summary27

v

Summary69

vi

Summary120

Summary158

Summary181

vii

Summary199

Index 209 viii

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Web Servers

This chapter introduces web servers, the services they provide, and how they work. This information is essential to web developers so they can make proper use of their web server and provide the best web experience to their users.

All web servers use the same building blocks to serve up web pages to the user. While we could look at all the available web servers, it really is not necessary since they all are designed around the same building blocks. Instead, we will concentrate on the Apache web server since it is the most popular. All the other web servers use the same building blocks and design principles as the Apache server.

Glossary of Terms

When delving into technical information, it is important that you understand the terminology used. For that reason, please review the following web server terms:

Common Gateway Interface (CGI) : This describes a process that serves up a dynamic web page. The web page is built by a program provided by the web server administrator. A common set of information is available to the program via the programs environment.

Hypertext Transport Protocol (HTTP) : This is a set of rules used to describe a request by the user to the web server and the returned information. The request and the reply must follow strict rules for the request to be understood by the server and for the reply to be understood by the users browser.

Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) : This code is used to build a web page that is displayed by a browser, and the Apache web server is used to serve the web page to users (clients). There are several versions of this code, but we will be using the latest version (5.0) in this book.

Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) : These sheets define the styles to be used by one or more web pages. These styles are used to define fonts, colors, and the size of a section of text within a defined area of the HTML page.

These terms should give you a good starting point for discussing how a web server works. All of these terms will receive wider attention and definition throughout this book.

The Apache Web Server

The Apache web server (today this is known formally as the HTTP Server) dates back to the mid-1990s when it started gaining widespread use. The web server is a project of the Apache Software Foundation, which manages several projects. There are currently more than 200 million lines of code managed by the foundation for the Apache web server. The current release as of this writing is 2.4.41.

Starting with Apache version 2.0, Apache uses a hook architecture to define new functionality via modules. We will study this in a subsequent chapter.

When you first look at hooks, they will seem a little complicated, but in reality, they are not since most of the time you are only modifying Apache a little. This will reduce the code you need to write to implement a hook to a minimum.

The Apache web server uses a config file to define everything the server needs to know about all the hooks you want to include in Apache. It also defines the main server and any virtual servers you want to include. In addition, it defines the name of the server, the home directory for the server, the CGI directory to be used, any aliases needed by the server, the server name, any specific handlers used by that server, the port to be used by the server, the error log to be used, and several other factors.

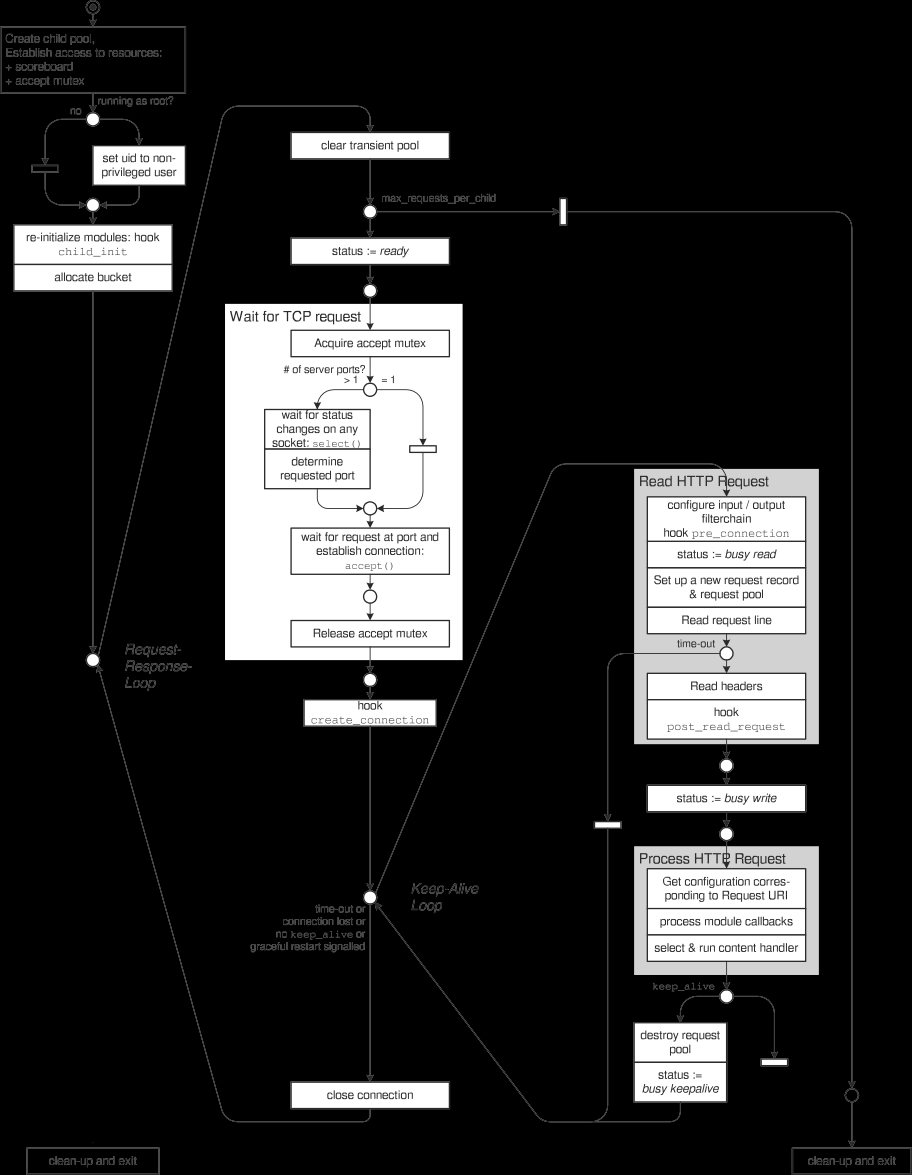

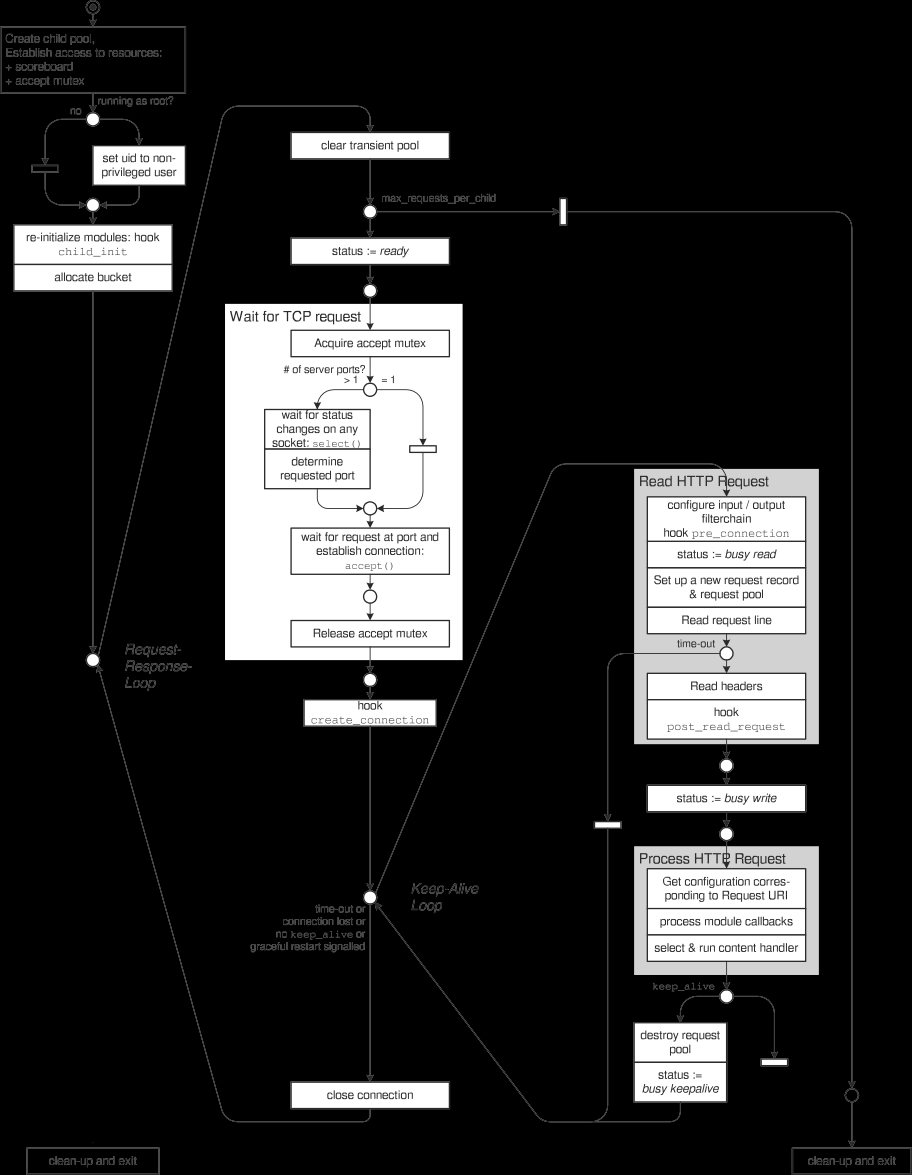

Once configuration is complete, the Apache server is now ready to supply files to a client browser. This is called the request-response cycle . For each request sent by the browser to the server, the request must travel through the request-response cycle to produce a response that is sent back to the browser. While this looks simple on the surface, the requestresponse cycle is both powerful and flexible. It can allow programs you create, called modules , to modify both the request and the response in many flexible ways. A module can also create the response from scratch and can include inputs from resources outside of Apache, such as a database or other external data repository.

Figure 1-1 shows the request-response loop of Apache plus the startup and shutdown phases of the server.

Figure 1-1. The Apache request-response loop

Modules not only can be used in the request-response cycle but in other portions of Apache such as during configuration, shutdown/cleanup, processing security requests, and other valuable functions. As you can see, modules allow flexible and powerful methods to be created by the server administrator to help with providing a great experience for their users.

Modules are not the only way to create dynamic web pages. Another way is by invoking available Apache services that can call an external program to create the page. The CGI process is usually invoked to supply this service, but there are other ways as well. Each of these ways will be examined in this book. It will be up to you to decide the best methodology for use in your environment.

The shaded request/response loop can have several forms. One such form is as a loop inside one of several processes under Apache. Another is running the loop as a thread inside a single process under Apache. All of these forms are designed to make the most efficient process of responding to a request that an operating system may provide.

The Keep-Alive loop is for HTTP 2.0 requests if supported by the web server. It allows the connection to stay open to the client until all requests have been processed. The loop here describes how a single request is processed by Apache. If the web server is not running HTTP 2.0 requests, then each request/response will close the connection once the response has been sent.

Nginx Web Server

The Nginx server was designed as a low-cost (in terms of system requirements) alternative to the Apache server. Probably the biggest difference between Nginx and Apache is that Nginx has an asynchronous event-driven architecture rather than using multiple threads to process each request. While this can provide predictable performance under high loads, it does come with some downsides. For instance, a request can end up waiting in the queue longer than the request attempt will survive on the network; i.e., the requester can give up before the request is ever processed if there are too few processing routines. While this problem is not exclusive to this server, it does still exist.

Recently the Nginx server has become popular within the community because of its smaller footprint and flexible design. However, since many of the principles that we will use to describe the Apache server also apply to the Nginx server, I will not delve deeply into Nginx and will discuss it only when differences between the two servers are important, especially in regard to dynamic web page design.

Apache Tomcat Server

The Apache Tomcat server is written in Java, which makes it difficult to compare to the more standard web servers. While some principles of dynamic web page design are similar, there are many differences. Therefore, and because its less commonly used than Apache and Nginx, I will not attempt to cover it in this book.

Configuring the Apache Web Server

Figure 1-1. The Apache request-response loop

Figure 1-1. The Apache request-response loop