Contents

THE

ACCUSATION

BLOOD LIBEL

in an American Town

EDWARD BERENSON

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

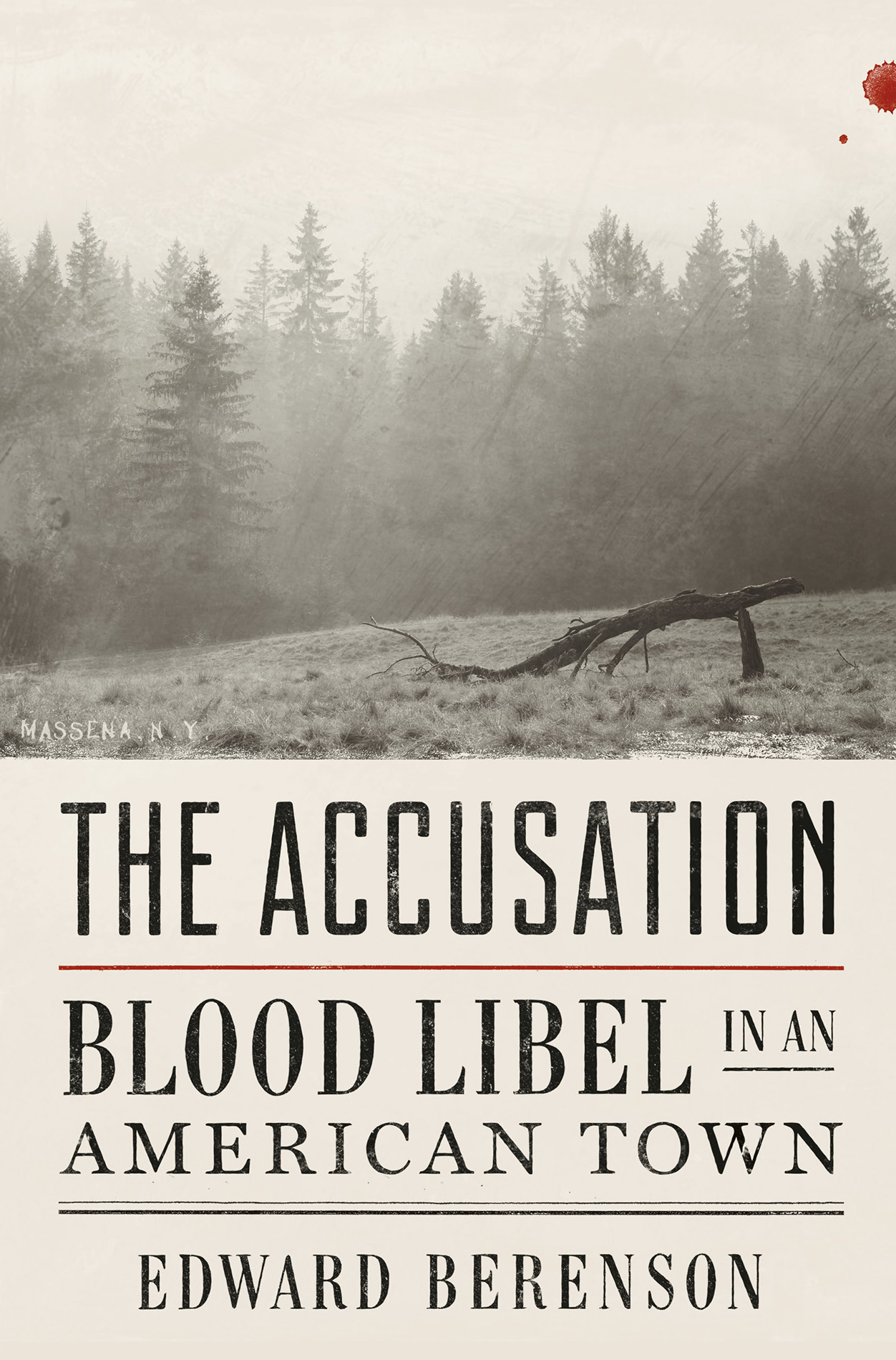

Barbara Griffiths, age four

Her parents were frantic and the townspeople on edge. Everyone knew Barbara, who was an adorable post-toddler and wise beyond her years. A picture taken shortly before Barbaras disappearance shows her with page-boy hair and a pensive smile. She stands at a right angle to the camera, but her head, slightly bowed, faces the photographer boldly. Shes neatly, but not fancily, dressed, with loose leggings, a dress floating just above her knees, and a short double-breasted coat. Most adults would have found her precious, which is why so many had jumped so readily into the effort to find her.

Had Barbara fallen and hit her head? Had she been attacked by animals? Indians? An escaped criminal? Or had something more diabolical taken place?

Several hours into the search, someoneits unclear whofloated the idea that Barbara had been kidnapped and killed by the Jews. She was the victim, voices said, of ritual murder, of the Jews supposed need to ritually kill Christian children and harvest their blood. The legend of ritual murder, one of the ugliest and most persistent features of the antisemitic imagination, first emerged in medieval England. It held that Jews required young Christian blood for matzo-making or other darkly religious needs. Corporal H. M. (Mickey) McCann, the state police officer called in to direct the search for Barbara, said the ritual murder accusation originated with a foreigner living in town and that he believed it.

In any case, the accusation of ritual murder suddenly took hold. The mayor, state police officers, and hundreds of villagers

Why Massena, New York? And why there but nowhere else in the United Statesand at no other time? What did the accusation and its outcome say about the place of Jews in American life, especially in the wake of intense, weeks-long press coverage of the incident nationwide? And how, ultimately, did American attitudes about Jews compare with European ones?

These questions, and others, moved me to delve into what would be both a personal family history and the history of the blood libel against the Jews. I was born in Massena, my fathers birthplace as well, and my research took me back to the village for the first time in nearly forty years. My great-grandparents, Jesse J. Kauffman and Ida Tarshis Kauffman, were perhaps the first Jewish residents of the village, landing there in 1898 with their two baby girls, Harriet (my grandmother) and Sadie. Their son Abe was the first Jewish child born in the village. Both Jesse and Ida had come to the United States as teenagers in the early years of the massive Jewish influx from Central and Eastern He followed the Erie Canal north to Albany, then west to Utica, and finally due north again until he ran into the St. Lawrence River and the Canadian border at Ogdensburg, New York.

As a male, even a young one, Jesse could emigrate by himself. Ida came with her brother and his family, and their trajectory stretched from Boston to Burlington, Vermont, before arriving in Ogdensburg at around the same time as Jesse in the early 1890s. Ida ran a small general store until she married Jesse in 1895. The couple soon decamped to Massena, attracted by business opportunities in a town whose economy seemed about to take off. It had been an agricultural backwater until then.

Massena was the last part of New York State settled by Europeans. After the American Revolution, the U.S. government gained rights to the area by giving the Mohawk Indians a lump sum and the promise of annual payments. This transaction was interpreted differently by the United States and by the American Indians, and ownership of parts of the land remains in dispute to this day. U.S. officials believed the land belonged to the government, and they urged people to move there to prevent the British from pushing the Canadian border to the south. Most of the newcomers hailed from New England and came in search of cheap, arable land, though the climate was rude, with winter temperatures sometimes dropping to 30F. The St. Lawrence River drew settlers as well, since lumbermen could fell trees

Massena, New York

The town of Massena itself is far from beautiful, sitting as it does on the flat plain that extends from the St. Lawrence River to the first rises of the Adirondack Mountains. The mountains are stunning, and each season gives them a different kind of beauty, from the glistening snow of the long winter months to the dark waters of the pristine glacial lakes. Just north of Massena, the St. Lawrence River flows lazily toward the town before erupting into the Long Sault rapids. This roaring waterway divides the St. Lawrence into separate channels, long impassible on the north side and navigable downstream only on the south. These rapids would be tamed only with the building of the St. Lawrence Seaway in the late 1950s.

Two tributaries of the St. Lawrence, the Grasse and Raquette Rivers, cut through the village of Massena and give it a certain charm. The various bridges that cross the waterways distinguish Massena from other, riverless upstate towns, although spring floods regularly washed the bridges away. These flowing tributaries encouraged the building of sawmills, gristmills, cement mills, and woolen mills, all of which lifted the economy but did little to beautify the town. Still, by the 1920s, Massenas Main Street would boast two rows of solid-looking brick and limestone buildings, many of them housing Jewish shops.

Side streets accommodated dozens of impressive homes. Industrial workers, however, lived in modest quarters. The Alcoa Aluminum plant, built close to the St. Lawrence, marred certain river views, but elsewhere in Massena, the St. Lawrence shimmered majestically to the north. Equally impressive was Barnhart Island, one of the largest of the great rivers many slivers of land. Massena annexed the island in 1814, after the close of the British-American War of 1812.

Main Street, Massena, late 1920s

American Indians had lived in or traversed what became Massena for hundreds of years before 1812. The pioneering Europeans who settled in Massena after the American Revolution found themselves isolated from the rest of the United States, perched as they were in an ill-defined borderland on a northern edge of the country. They found themselves hemmed in to the north and west by the St. Lawrence River, which was frozen three to four months of the year, and to the south by the forbidding Adirondack Mountains. The Erie Canal was a rigorous 150 miles to the south, and the sole route east to Vermont depended on a narrow footpath that snaked through thick forests and dead-ended into Lake Champlain.

Massenas early inhabitants likely didnt feel much sense of belonging to the United States; the town was named by French-speaking migrants after the Napoleonic general Andr Massna. This was an odd choice perhaps, since his armies committed terrible atrocities in Sicily and elsewhere during the French military campaigns. In the Massena case, this explanation would not suffice.

Next page