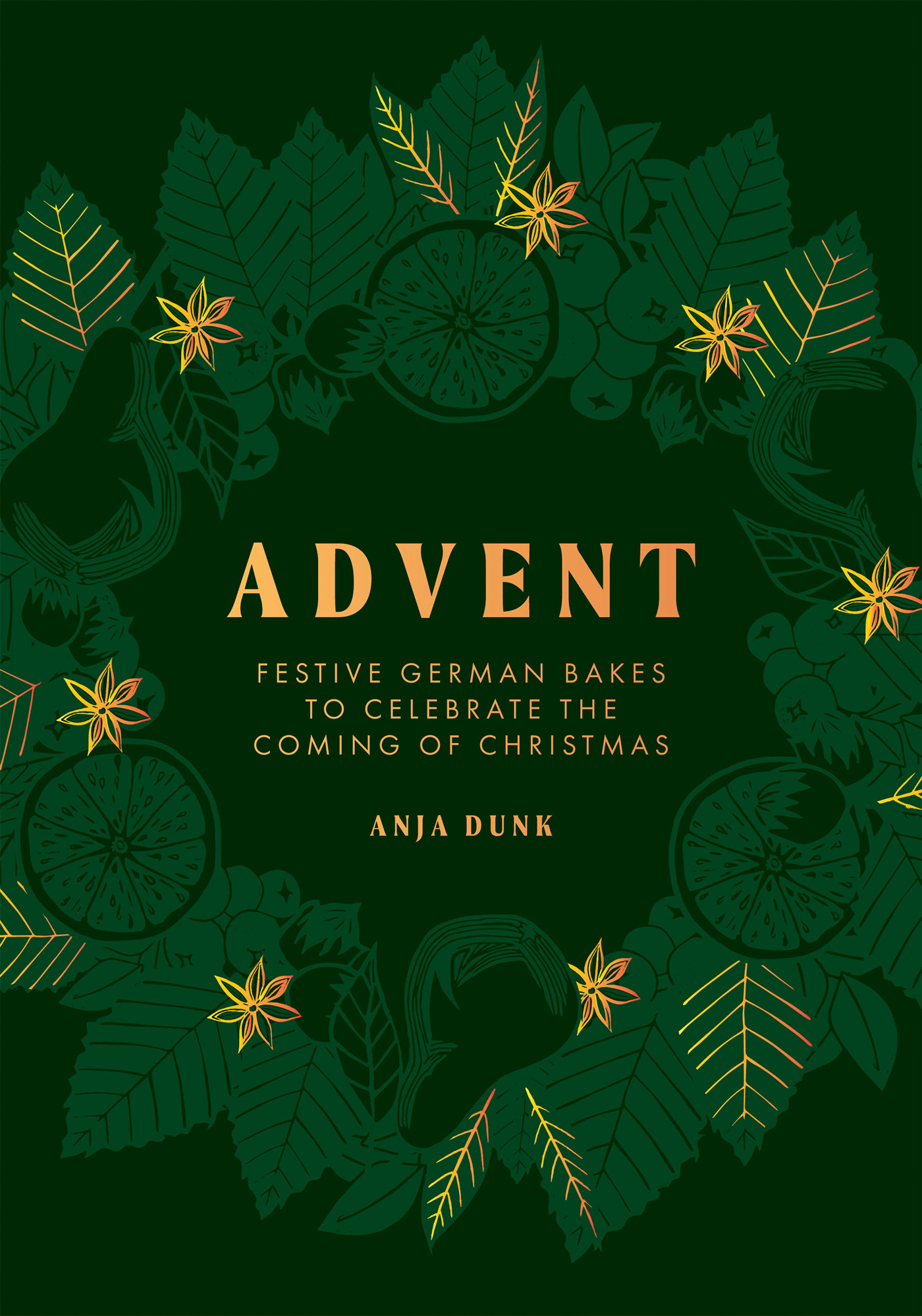

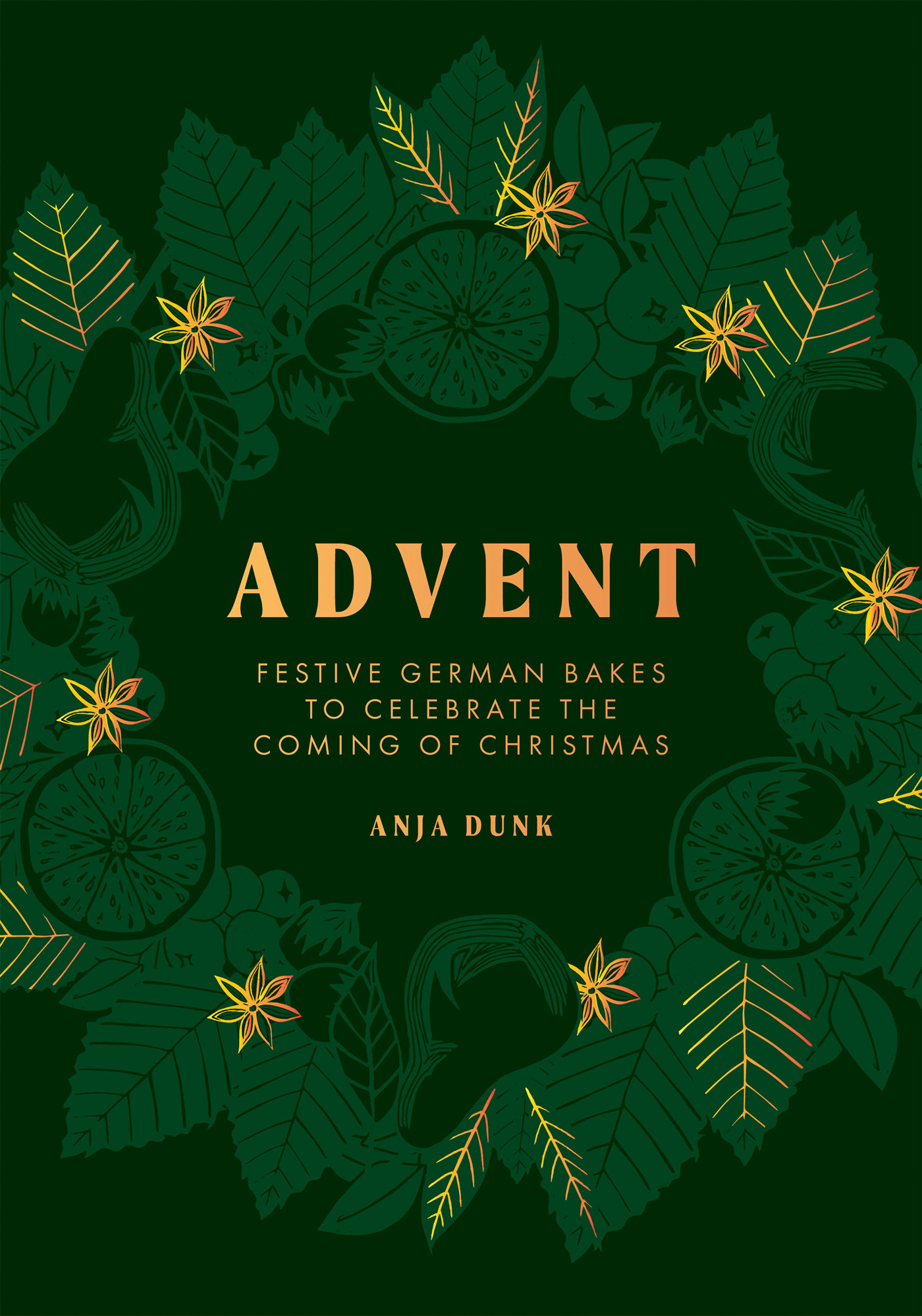

Advent is a magic time. It holds all the sweet, almost unbearable anticipation of Christmas for days on end and its such a big part of our life each year that we treat it as a fifth season. It starts on the fourth Sunday before Christmas and sits snugly in between autumn and the winter solstice (give or take a day or two).

Advent celebrations, of which baking is a vital part, are synonymous with German winter culture. The Christmas cookbooks come down off the shelves around about the same time as the thick coats come out of the wardrobes. Each day throughout Advent friends and neighbours visit each other to exchange packets of homemade cookies wrapped up with ribbons. Kaffee und Kuchen takes on a new meaning during this time, when every German household offers up a Bunter Teller a colourful plate of Advent biscuits (cookies) alongside the coffee. The conversation around the table is generally led by the festive biscuits, and in the spirit of Advent it isnt uncommon to leave the house with a new recipe or two tucked into your bag.

The Advent season is steeped in tradition and rituals and, just like the astronomical seasons, much of it is centred around light. The Advent wreath, traditionally a doughnut-shaped circle made of twisted pine branches, sits on our kitchen table and is adorned with four candles. Each candle represents the weekly run-up to Christmas and is lit at mealtimes, providing precious light and warmth during the shortening days.

A slightly less obvious but equally symbolic, and arguably more important, sign of festivities is the oven constantly aglow in our home during this period, scenting the house with cinnamon, ginger, cardamom, clove and anise as tray upon tray of mouth-watering biscuits bake. It is this smell, of biscuits, spice, candles and pine combined, that is so unique to Advent.

Lebkuchen are the first biscuits to fill the kitchen with the presence of Advent. Theyre one of the more traditional bakes, engulfed in history and sweetened with honey. Cinnamon stars with a cap of snowy white frosting, meltingly soft vanilla and butter crescent moons, jam-filled ginger hearts, caraway and lemon stars with icing that shatters between your teeth like a thin layer of ice, hazelnut and coconut macaroons, rum truffles, Dominosteine, marzipan-filled Stollen, gingerbread houses dripping with candied fruit and sugar icicles, chocolate-dipped Spritzgebck and many more biscuits and sweet treats soon follow suit.

The glass jars on our kitchen shelves transform from their everyday job of housing basic dry ingredients into a fairy-tale wall of sugar and spice, each jar filled with a different biscuit that instantly transports us to snowy Bavarian towns and twinkling Christmas markets.

Much of the baking of Adventsgebck is done together as a family. Its a messy affair with icing sugar flying through the air, sprinkles and silver balls skittling around the table and, as you can imagine, much excitement. Never is our oven used more than during the run-up to Christmas. As we hunker and snuggle around the stove each day, we are entertained, warmed and comforted by it. If ever there were a time for the oven to prove its worth as the real hearth of our home, Advent is it.

A Bunter Teller directly translated means colourful plate and it is in fact a colourful plate of Advent biscuits (cookies), probably one of the most German of German traditions and something that no household in the country is without during the month of December.

Making homemade biscuits, even for those of us who never normally bake, becomes a national pastime at the end of November and throughout the last month of the year, so that the supply of Weihnachtspltzchen (Christmas biscuits) intended to see you through the Advent period never runs out. The order in which they are baked acts as a calendar, a countdown measured in biscuits. The butter-less biscuits, many of them old-fashioned varieties such as Lebkuchen, which keep the longest, are baked first, followed by nut biscuits, then macaroons and meringues. We bake butter-rich ones such as Vanillekipferl after all of the aforementioned, and finally the last things we make are all the sweets and truffles. The biscuits are usually stored in a towering stack of tins kept at the ready to plate a selection up whenever neighbours and friends pop round.

One of the things I enjoy most about visiting friends during this period is the quiet sense of pride that ascends as the Bunter Teller is placed on the table. Its inevitable that every biscuit has a story, usually attached to a person, and as each biscuit is carefully selected and eaten the stories and recipes unfold along with them.

Much like decorating a Christmas tree, putting together a Bunter Teller is a seasonal necessity that is both bound by ritual and habit, yet open to new additions. Choosing what biscuits end up on the plate is not too dissimilar to how one might choose cheeses for a cheeseboard a selection that is varied in both taste and texture and something for everyone is the general rule of thumb.

On Christmas Eve in our house I tailor-make an individual Bunter Teller for everyone in the family; these include sweets (candies) and confections as well as biscuits and are placed under or near the tree for all-night grazing purposes. Its also commonplace to add a satsuma to each plate and a handful of nuts to be cracked open using a traditional Nuknacker. As a child I can honestly say I was more excited about the prospect of what I might find on my Bunter Teller than about everything else under the tree, and its still true today.

The most memorable Bunter Teller Ive ever received, though, was during the Christmas of 1999 when I lived in Beijing. Far away from family and missing the familiar build-up, rituals and traditions of Christmas at home, my roommate Jenny and I spent hours soothing each others homesickness by talking about these very things, hopeful that bringing them alive in conversation would make us feel surrounded by them in person.

I spent Christmas Eve teaching small children (all blissfully unaware of the days significance) English. Despite not being all that late, it was already dark as I left the classroom and made my way alone back to our room, through the biting-cold wind, scarf pulled up over my mouth and nose, thinking of the annual family Christmas walk to the beach that I wasnt on.

Feeling low and close to tears, I turned the key in the lock to room 508 and pushed open the squeaky scuffed door to a room aglow with candles arranged in an almost shrine like manner surrounding a Bunter Teller. Surprise! beamed Jenny with her arms held out, and as we hugged I cried and laughed and gulped in the beauty of the moment it was everything. I felt like I was home.

Unusually for me, I didnt really give a damn about what was on the plate. As it turns out, while I was teaching, Jenny had spent the day traipsing around the freezing city on an elusive European biscuit hunt. An hour before the shops shut she ended up finding a Lebanese bakery in the embassy area of town, where she bought a platter of baklava. And in a last-ditch attempt to make a Bunter Teller that was more than just that, she begged at a hotel kitchen and came away with some sort of Danish butter biscuits, all of which she arranged lovingly on a plate awaiting my return.

We Germans take our Advent baking seriously and the pinnacle of it all is the

Next page