In memory of my mother

Contents

The seeds of this book sprouted in 1992, when I made some really stupid mistakes.

I was working as a correspondent for the Reuters news agency when my boss sent me to Angola, a notoriously tumultuous African country. I was supposed to report on its first democratic elections. Until then, I had covered the odd riot, but I generally did business reporting or press conferences, where the biggest danger was being pushed out of the way by an aggressive cameraman trying to get a better shot.

Now I was in Angola. For thirty-five years a relentless civil war there had killed millions of people and left land mines strewn all over the country. Peace had been hastily negotiated just months before my arrival, but no one was sure it would last. Armed guerrillas were roaming around the country under the leadership of Jonas Savimbi, a venal sociopath known to burn people alive. He was the sort of guy who raped underlings wives and starved entire towns because he didnt like their party politics. Savimbi had already made clear that he had to become president. For some reason my bosses and I hadnt considered what might happen if he didnt. After all, he was an egomaniac. Well, Savimbi lost the elections. In response, he ordered his men to pick up their rocket-propelled grenade launchers and go door-to-door to round up critics. Suddenly, roadblocks popped up on my way to interviews, and a car bomb exploded and shooting erupted near my hotel. I was clueless about these new working conditions and actually thought one should run toward heavy-caliber machine-gun exchanges to see what was going on rather than cower at a safe distance. My only previous experience with battle was watching World War II movies with my father, who once showed me the Mauser rifle he had lifted from a dead soldier. I had no idea how it worked. That was the extent of it.

Its amazing that I got out of Angola in one piece. I did dumb things, like navely stroll through a mine dump filled with smoking shells. It didnt occur to me that my leg could be blown off if I stepped on the wrong spot. I had also packed the wrong malaria medication and got a 102-degree fever that lasted for days. When I recovered, Savimbis number two came to my hotel lobby to tell me that he didnt appreciate my reporting. Youre not writing positive things about us, he said. Gripping my wrist in his fish-cold hand, he warned me to leave town or else. I wasted valuable days deliberating how to respond to this death threat, and by the time I finally decided to make a dash for the airport, the fighting had spread to the tarmac and all flights out were canceled. Rebels, meanwhile, had thoughtfully mined roads and blown up bridges, so driving across the nearest border wasnt an option, either. Stuck in the capital, Luanda, I strayed into a courtyard of snipers and nearly got shot in the forehead. I also wasnt dressed for successsuccess being survivaland scurried about in flimsy Keds. Flak jackets? Never heard of em. Finally, I sabotaged my only communication with the outside world, the ten-thousand-dollar satellite phone my editor had given me, one of a mere handful in town, when I failed to plug in a surge protector during one of the constant blackouts. The phone had to go to a repair shop, and there wasnt one in all of Angola. Lest you think I was a complete fool, let me say that such ignorance was common in those days. At that time, the news business didnt have safety protocols. We simply headed to a sketchy area with a bottle of Bells whisky and cries of Good luck! The office would rejoice if you came back intact. If you didnt, the boss would hold a memorial and send flowers to your family. If you were really popular, someone would open a single malt and pass it around the newsroom.

Eventually, the man who wanted to execute me was shot in the legs (not by me), so I didnt have to worry about him anymore, and battles at the airport stopped long enough for commercial flights to resume. On the plane back to Johannesburg, where Id been living for the past year, I ordered a sparkling brut to celebrate the safe exit. But I had a nagging suspicion that with some simple homework and fore-thought, I could have operated in a more prudent manner.

That conviction grew deeper as my career unfolded over the next few decades, on five continents. Ive since reported on seven civil wars, one genocide, several separatist rebellions, and forty-eight assorted rogue militias, gangs, vigilantes, and drug cartels. The civil unrest and mob situations I covered probably number in the hundreds. As time went on, equipping myself with contingency plans and risk analyses, I felt more confident going into other problematic situations, like landslides and gloomy American neighborhoods and middle school soccer games. I learned how to negotiate with armed drunk teenagers at foreign checkpoints and to search under my Citi Golf for explosives. I discovered how to stay reasonably clean in a shelter and how to apply pressure to a spurting artery. I gleaned how to protect my phone conversations from Vladimir Putins intelligence agents and outwit policemen bent on rape.

As Confucius once said, He who fails to prepare, prepares to fail. Or as I like to say, Without proper planning, youre screwed.

I got into media safety training in 2005, after too many colleagues were maimed, raped, killed, or kidnapped. I had faced too many close calls myself, and it occurred to me, and others in the industry, that popping cheap airplane champagne after surviving wasnt an effective tactic. We needed to lessen the odds of fatality by guarding against the perils. To that end, I incorporated new safety protocols into my classes at Columbia Universitys Graduate School of Journalism, where Ive been teaching for nearly two decades. Workshops that I ran outside the university blossomed into a consulting business for organizations around the world. And as one of the few women who did safety training, I honed primers that addressed the special needs of females.

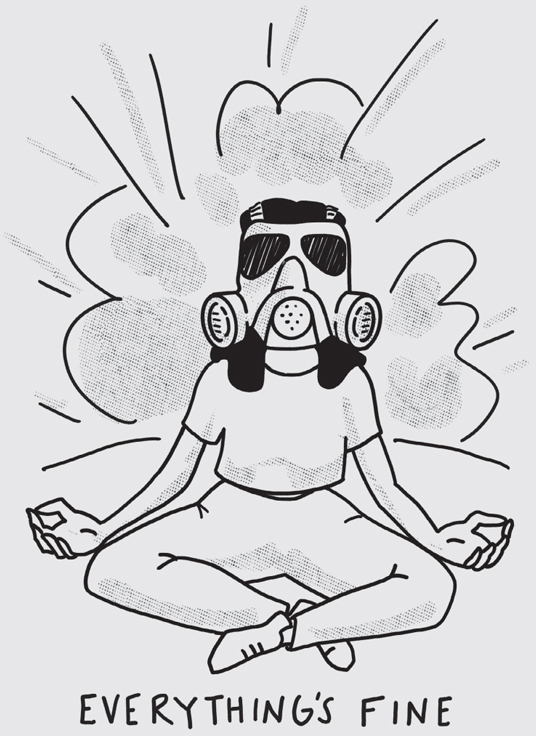

As my clientele grew, people began to approach me outside the small journalist community. Most of them were women, who felt particularly exposed to danger and unsure how to react. There was a college junior who was spending a gap year in Jordan and wanted to know what precautions she should take. Someone who was vacationing in Puerto Rico during hurricane season asked about generators and contracting Zika while pregnant. Everyone wanted to know about preparing for the surge of natural disasters that have been hitting lately. In 2017, after a gunman massacred fifty-eight people at a music festival in Las Vegas, I received a torrent of emails from acquaintances, some of whom I barely knew. They wanted ballistic advice in case they faced similar situations. Should they run bent over in a zigzag pattern, like in the movies? (Answer: That depends.) Should they fashion tourniquets from belts? (Negative.) Where was the safest place to sit at stadiums? (Near an exit.) Should they no longer take kids to concerts?

Their questions are reasonable, considering that more than four hundred Americans perished from mass shootings in 2019 alone. Random citizens have been slaughtered in schools, nightclubs, churches, and streets. Demonstrations are increasingly turning violent, even fatal. Recent events have taught us that everyone, from neighbors to postal workers, should know how to identify a pipe bomb. Experience with violence is no longer limited to the few of us who report on exotic wars and crises overseas.