GEEK SPEAK, TRANSLATED

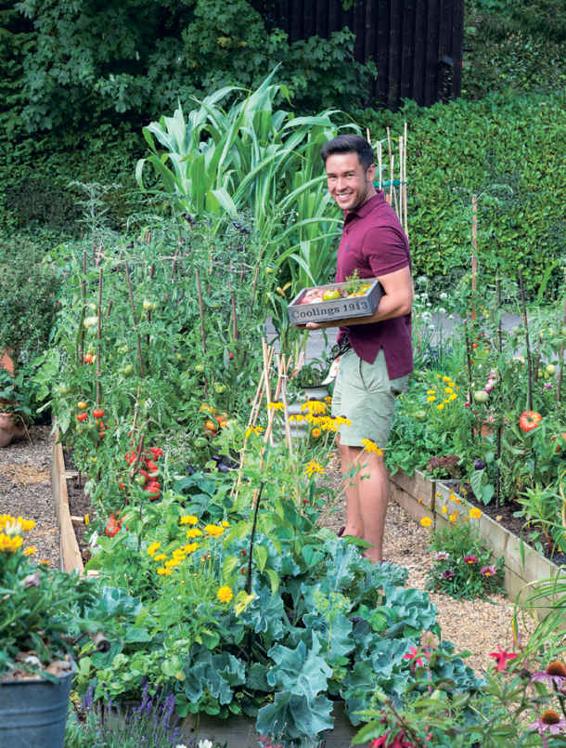

For an obsessive botanist like me, delving through thousands of scientific papers and trialling all manner of cutting-edge horticultural techniques has been an epic amount of fun.

Translating these mountains of academic geek-speak into a book of simple, realworld techniques that the most novice gardener can master, however, is not without its challenges. The simple fact is that, even with quadruple-tested recipes, results will vary according to a huge number of factors. Even the very nature of what constitutes good flavour is subjective, so I am the first to hold up my hands to say that there will be a certain amount of unavoidable personal bias here.

Academic journal entry this book is not, nor is it meant to be a textbook for agricultural engineers. Instead, it is an interpreted, evidence-based guide for foodie gardeners looking to score better-tasting harvests, no matter who they are or where they live.

Contents

How to use this Ebook

Select one of the chapters from the list and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

To enlarge any of the illustrations or photographs, double click on the image and it will zoom up to full-page size. Double click to return.

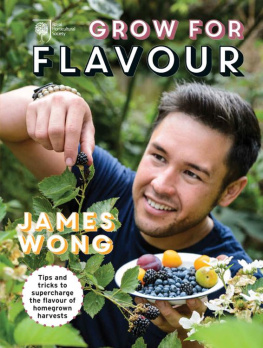

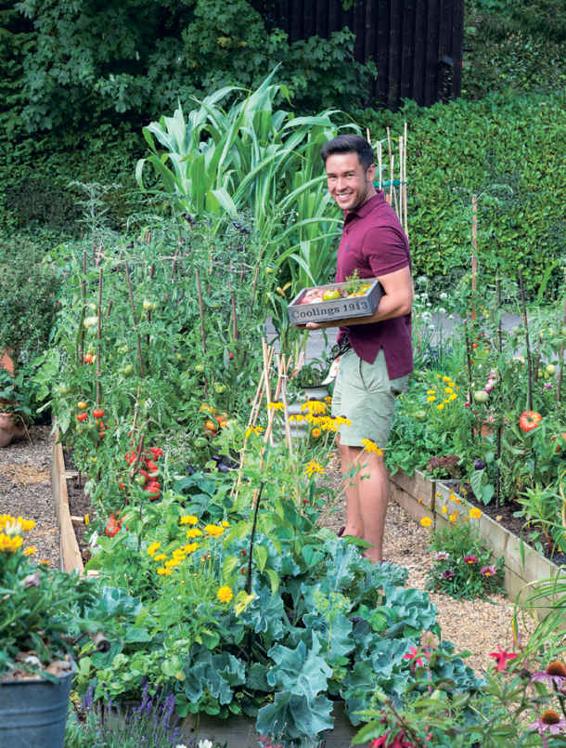

GROWING THE WONG WAY

Home-grown always tastes better than shop bought.

Does this sound a familiar promise to you? These, or words to a similar effect, seem to be the compulsory opening line to every article on growing fruit and veg that has been written in the last 20 years. To me as a scientist, however, theres just one problem with them: they are not necessarily true.

In fact, once you take into the account the I grew it, therefore it must taste better placebo, many home-grown crops in reality taste pretty much the same as (if not sometimes worse than) their supermarket counterparts. Im looking at you, celery, swedes and cabbages.

To me, the shocking thing is that a lot of standard gardening advice (essentially lifted from 19th-century agricultural practices) actually conspires to water down crop flavour in the all-consuming pursuit of yield above all else. As a final blow to a foodie growers morale, many of the horticultural rules we adhere to with slavish devotion are often either based on pure myth or have only limited scientific basis. But this does not have to be the case!

In this book I aim to turn the tables on conventional gardening advice, using the latest scientific research to allow it to live up to its No. 1 promise: delivering truly unsurpassed flavour. This unique, research-based approach ditches the traditional obsession with maximizing yield and can not only measurably improve the flavour of your crops, but could also dramatically reduce your workload, banish gluts and even boost the nutritional content of your harvest. Think of it as growing for maximum flavour and minimum labour, with some cutting-edge science to back it up. And Ill be busting some of the longest-held gardening myths along the way.

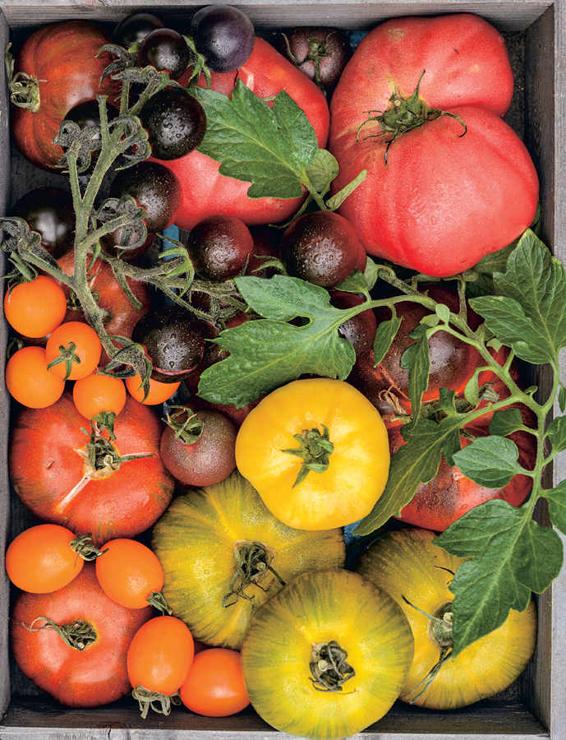

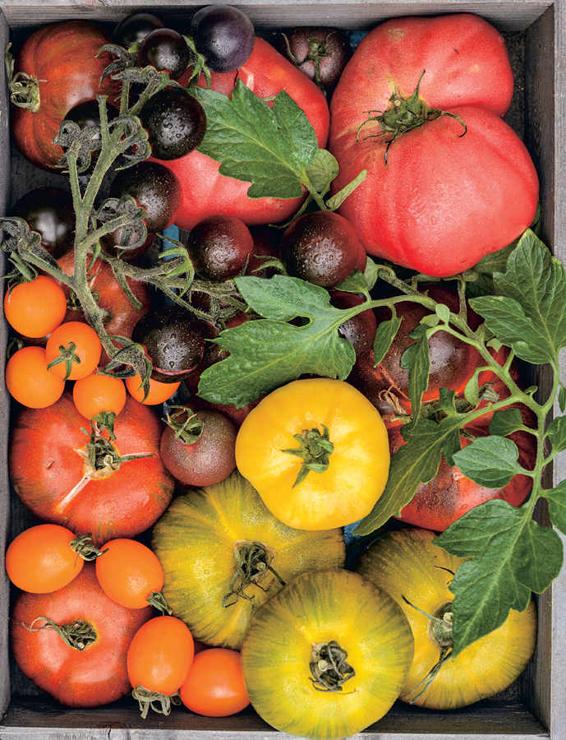

Following these principles could quite genuinely give you tomatoes that are more than 150 percent sweeter, strawberries with 100 times the aroma compounds, chillies with double the fire power and beetroots with three times less earthiness. My approach, devised after an extensive review of more than 2,000 scientific papers in journals from around the globe, aims to piece together the latest research on how variety choice and growing techniques can affect crop flavour, translating academic geek-speak into a simple set of tips and tricks that anyone can do.

I have personally tried and tasted the crops grown under this system and dozens of varieties were trialled at RHS Garden Wisley in Surrey. These crops might not give you record-breaking yields. They might not give you perfectly blemish-free, symmetrical harvests. They might not follow the rules your granddad taught you. But they will almost certainly guarantee you flavour that is second to none plus some very funny looks from the allotment old guard. So lets get started!

WHY WHAT TASTES GOOD, DOES

Ever thought that fish and chips taste better with a wedge of lemon? Well, believe it or not, thats millions of years of evolution guiding you instinctively to add the antibacterial chemical citric acid to kill the harmful germs that produce unpleasant fishy aromas. Depending on where in the world you were brought up it might not be lemons you reach for but chilli, tamarind, vinegar, wasabi, ginger or soy sauce instead. Yet all of these contain antibacterial substances that, like lemon juice, help combat off flavours and in so doing render the flesh safer to eat.

Even the Inuit, who have access to very few plant-based condiments, will ferment fish until its levels of antibacterial acetic acid peak before adding it to fresh fish as a germ-fighting seasoning. Whoever you are and wherever you live, the rawer and fishier your fillet, the more antibacterial agents you are likely to add.

In fact, our entire perception of good flavour is a complex collaboration between our senses of taste, smell and touch that has developed to perform two simple functions: keeping potentially harmful stuff out of our mouth, while allowing the good stuff in. This elaborate chemical detector has evolved over millions of years to be capable of sensing and evaluating thousands of substances, helping filter potentially toxic or germ-filled elements out of our diets, while causing us to seek those high in energy and nutrients. It is no coincidence that most dangerous toxins taste overwhelmingly bitter (a flavour most humans find unpleasant), while most high-calorie, safe-to-eat foods in nature taste sugary sweet. We rarely stop to question why we select, combine, prepare or cook ingredients the way we do, but at the root of all of these activities is the instinctual drive to consume safe, nutritious food. Far from being based on independent choice, the science of good taste is largely hard-wired into our genes.

HANG ON, ISNT FLAVOUR SUBJECTIVE?

While there are, of course, distinctions in flavour preferences between individuals and cultures,

Next page