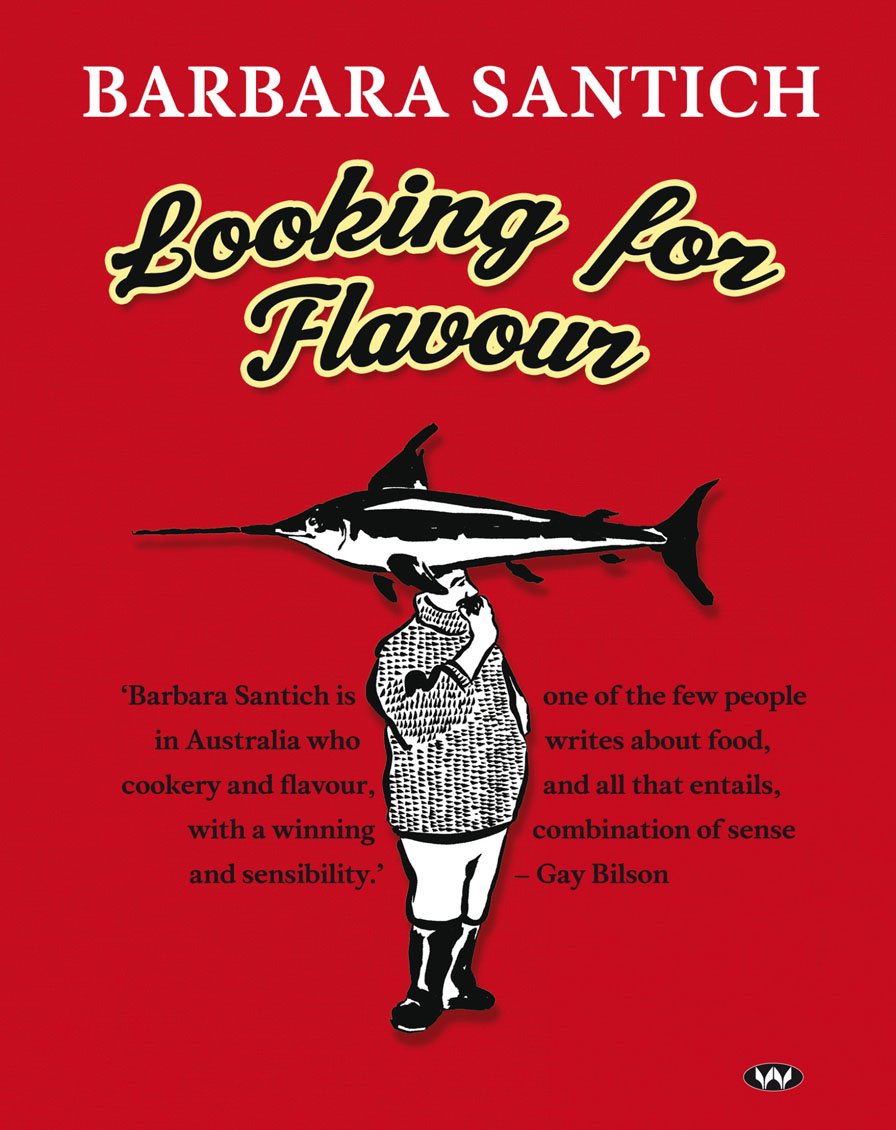

Santich - Looking for Flavour

Here you can read online Santich - Looking for Flavour full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Australia, year: 2009;2013, publisher: Wakefield Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Looking for Flavour: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Looking for Flavour" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

In this book renowned food writer Barbara Santich develops a credo for enjoying eating in modern Australia. With topics like flavour first, rainforests second, her book is sure to provoke passionate debate. ... a very pleasant nightcap in bed. - Graham Brown Visit Vineyards

Looking for Flavour — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Looking for Flavour" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

WAKEFIELD PRESS

LOOKING FOR FLAVOUR

Barbara Santich is an author, researcher, teacher and internationally acknowledged authority in food history. Fundamental to her work is a belief that what, how and why we eat is intimately connected to our culture. Looking for Flavour , recognised by the Food Media Club of Australia as the best soft-cover food book in 1996. is not only an individual adventure but also a key to understanding other societies.

Barbara Santich is also a respected academic at the University of Adelaide where she introduced postgraduate courses in both food writing and food history and culture.

Wakefield Press

1 The Parade West

Kent Town

South Australia 5067

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 1996. This expanded edition published 2009

Reprinted 2011, 2013

This edition published 2013

Copyright Barbara Santich, 1996, 2009

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Illustrations by Danny Snell

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Santich, Barbara.

Looking for flavour [electronic resource].

Bibliography.

ISBN 978 1 74305 208 2 (ebook: epub).

1. Food habitsAustraliaHistory. 2. FoodHistory.

3. Cookery, AustralianHistory. I. Title.

641.30994

For A.E.D.

When you wake up in the morning, Pooh, said Piglet at last, whats the first thing you say to yourself?

Whats for breakfast? said Pooh. What do you say, Piglet?

I say, I wonder whats going to happen exciting today? said Piglet.

Pooh nodded thoughtfully.

Its the same thing, he said.

A.A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh

Contents

FOREWORD

EARLY IN 2009 , at a Barossa Valley winery, a lunch cooked by two dedicated permaculture growers and chefs, Michael Voumard and Ali Cribb, made an emphatic statement about changes in regional Australian expectations of flavour and cooking techniques. Although the food said it all and needed no champions except by its contented consuming, one person at the table was moved to blame Silesian immigration for food unsuitable to the climate and these Germanic traditions and concomitant nostalgia for barricading Barossa cooks from modernity and climate-dictated kitchen practice. This seemed a tad unfair to me, even reactionary, and more about marketing by abuse than anything else. The blame was as much a sign of the culinary times as was the meal.

Every course we ate depended on, or was supported by, the productive garden this Barossa winery supports. Even the chickpeas, which bound a yabby soup, had been grown here. One of the many courses was served in three parts, all of which featured very young green beans picked that morning. The first was beans, rocket and a barnaise sauce that rescued French haute cuisine from any imagined slump. The second was beans cooked in the southern Indian way, with coconut and mustard seeds, curry leaves and chilli. The third was beans prepared as though we were in South-East Asia, combining the flavours and textures of salted duck eggs, tiny sauted peanuts, fish sauce, shallots, lemongrass, lime juice and chilli.

With the exception of saffron, spices and peanuts, the produce we ate was local. It was spectacularly fresh and full of flavour: zucchini, tiny onions, beetroot, peas, salad leaves, herbs, apricots, white and yellow peaches, black mulberries and cape gooseberries, but it was the three green bean dishes which made one think about professional Australian cooking. You would be forgiven for thinking this meal, and particularly the use of the beans, as being all over the place. One minute you were swiping a bean through a perfect barnaise and wholeheartedly thanking the French for the sophistication of haute cuisine; in another mouthful, the lovely rounded flavours and textures of the Indian sub-continents coconut palm and spice country seduced us, and with the next we were assaulted by pungent Thai flavours with their perfect combination of sweet, salty, sour and hot elements. The main course, by the way, was local pork adobe which beckoned Mexico to join a united nations of cookery.

And, yes, the meal was, literally, all over the place. For someone like myself who still worries that Ive transgressed by serving a meal made up of dishes from different parts of India, or worse, mixed Muslim with Hindu dishes, or worse still, often think I should leave Indian food to Indians in India (age and puritanism the factors, I suppose, but also validated by the fact that food tastes and smells differently in situ), this lunch, which was near globally inclusive, should have finished with confession rather than Mexican organic coffee. Anthropologist Ghassan Hage might conceivably feel sympathy for my dilemma as he has written much about the imbalance of power between the host and the migrant, making the point that in culinary terms, multiculturalism in Australia has benefited the host and made an object of the migrant. This I think is true of the educated middle class who gain much of their culinary curiosity and knowledge through travel rather than tasting foods of different ethnicity in Australian cities. Certainly my interest in Indian food is the result of travel rather than knowing Indians in Australia or eating at Indian restaurants here.

Instead of feeding my culinary intolerance and puritanism, the meal at the winery worked as a kind of enchantment, not so much because of its culinary diversity, but because it was so well cooked. See, smell and taste, the cooks seemed to be saying, and you will understand the intoxication of our heterogenous practice. Heterogenous: originating outside the organism.

Ive made much of this meal because it speaks volumes about how we Australians might eat now. Despite, or perhaps more correctly because of its marriage of disparate culinary techniques it was bursting with authentic flavours. In one of her essays, Recipes and Rights, Barbara Santich defines authentic as the flavour of things tasting as they should. How things should taste depends on what you have tasted before, but at the very least, as Santich writes, authentic flavour begins in the garden with soil and climate. When a dish is full of flavour, it is because the cooking has not robbed the produce of its quiddity, its authenticity. I agree with her that culinary authenticity is a bit like the Holy Grailit would clarify everything, if only you knew where it was. Santich argues that if we fix authenticity to a time and place then we dont allow it any natural mutation. Interestingly, at the close of this particular essay she remains firmly on the side of the ur-pesto sauce which has spawned a few post-modern grand-nephews and nieces. It is, I suspect, the name that needs to be kept for the original.

The development of language makes an interesting comparison with recipe variation and mutation, and language surely developed and mutated as people gathered around a hearth to dine on food cooked over a fire (but also perhaps because individual homo sapiens strayed away from the pack and needed to describe something unseen?). The anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss famously posited that food was good to think and bio-archaeologist Martin Jones, in Feast: Why Humans Share Food , interprets Mary Douglas work on the shared meal as, in summary, food is good to communicate. Of course both were referring to the development of the brain, society and culture, not to thinking directly about food.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

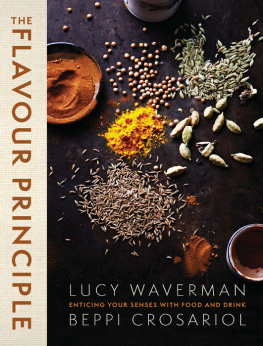

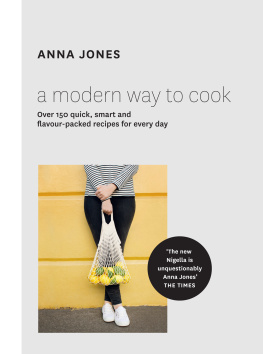

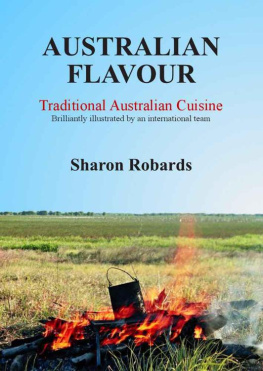

Similar books «Looking for Flavour»

Look at similar books to Looking for Flavour. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Looking for Flavour and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.