My Sindh

A journey to the beloved homeland

Shakuntala Bharvani

black-and-white fountain

Copyright 2021 Shakuntala Bharvani

Published by black-and-white fountain

ISBN 978-93-83465-26-2

ebook ISBN 978-93-83465-24-8

Book design and cover design: Veda Aggarwal

Editor: Saaz Aggarwal, with inputs from Mohindru Mirchandani

We are grateful to Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro for the image of Satiyan jo Asthan with Lansdowne Bridge in the background, used on the cover.

Email: blackandwhitefountain@gmail.com

http://blackandwhitefountain.com/

http://sindhstories.wordpress.com/

To my IRB,

Whose knowledge and love of Sindh

inspired this book.

For our children,

Vandana and Dhiren, Vedant and Veer.

May they be inspired by these stories

of courage, conviction, and community.

Contents

A note on the style used in this book

This book follows a language style on the spectrum between British and American usage, a middle ground generally considered acceptable in the globalization of the language. It chooses the idiomatic flow of contemporary English, lenient of an assortment that might include program, aeroplane, and others, as relevant or convenient. In quotes from other sources embodied in the text, the style of the original has been retained, resulting in style inconsistencies from time to time. Logic, common sense, and the readers comfort have been prioritized over finicky commitment to rules. Captions of images display names of people from left to right. Abbreviations do not use full stops; double quotes have been used for conversation and single quotes for emphasis. While measurement uses the metric system, miles, pounds, and feet have been retained where contextually appropriate.

This is a book of history and nostalgia, and moves freely between the past and the present. Original place names, the ones she has been used to, mean a lot to the author, and the reader is requested to excuse the frequent and inconsistent use of Calcutta for Kolkata, Bombay for Mumbai and so on. Sindh was called Scinde, Sinde, and Sindy by the British. In this book, the contemporary spelling Sindh is used. Hyderabad, Sindh, in most instances, is just Hyderabad.

Italics is always a tricky business, and many Indian words likely to be familiar to readers of this book have been left in straight face, as to italicize them would be to interrupt the smooth flow of reading. In the text version of this book, Sindhi words are presented in a font that simulates the Sindhi script, with a view to nudging readers towards their heritage. Unfortunately, this was not possible in this e-version. Most meanings have been provided within brackets or dashes, but there are quite a few non-English words and phrases that have been left untranslated (Chikni Chachi is an example) because of the challenge of providing sufficient meaning and context in a short space. In such cases, readers are requested to consult Google if required.

The author of this book has been a professor of English for more than four decades, and in this book she has used a conversational style spiked with humour and irony. An astonishing number of sentences begin with And and But! However, her writing is also strewn with literary allusions. With respect and affection for her young readers, she has tried to explain each one in the course of the text, but here, too, readers may want to reach out to the internet for further explanation.

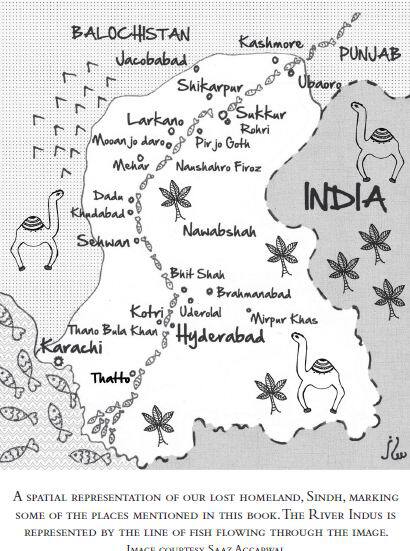

Spatial representation: Sindh

1. Crocodiles, camels, and Quetta

The author walks around the Calcutta Zoological gardens with her brother Ajit, and wakes up to the fact that crocodiles form a part of our Sindhi heritage.

M y brother Ajit, who is just two or three years older than I am, has a fantastic memory and remembers several incidents which took place during our childhood of which I have not the vaguest remembrance. Sometimes I wonder if he is making up stories just to impress me. For suddenly he will come up with something like, You know what happened to me in Quetta when I was three years old? I ate five pounds of grapes at one sitting and then I was sick for five days.

I try and believe him because, after all these years, I know that much of what he says is true. His memory is extraordinary! Yes, Quetta did have the most juicy, mouth-watering grapes. And not just grapes but all varieties of fruit: sweet rosy apples, plums, peaches, pomegranates, apricots, cherries and the incomparable sarda, a variety of melon, that my parents often spoke of in later years, with nostalgic longing. It is not without reason that Quetta was referred to as the fruit basket of Sindh. But how could a child of three have ever eaten five pounds of grapes in one go?

Ajit was a pre-Partition child, born in Karachi in 1942, and he has vivid memories of St Patricks School which he attended very briefly. He remembers being told that he was born in a maternity home run by a Malayali lady, Dr Anna Thomas, on Bunder Road in Karachi. And he even remembers the name of the steamer in which our family sailed from Karachi to Jam Khambalia: SS Sonavati, when raging riots broke out and there was no choice for Hindus but to flee the newly-formed country named Pakistan. He remembers my father explaining to my grandmother that travelling by train was risky because Hindus trying to escape on trains were being slaughtered or robbed.

He also has vivid memories of our arrival at Jam Khambhalia, a port in Gujarat, where we stayed at a guesthouse belonging to a Gujarati family my father had known and worked with in Quetta. He can recall the railway station close by, and the durwan who used to sit at the entrance. And then, according to his story, he went and met the old durwan on a visit to Gujarat a few years ago and surprisingly the durwan recognized him! Apparently the ninety-year-old former durwan said, Of course I remember you, sahib. You climbed that tree there and fell and broke your arm and then you screamed and cried. I carried you in my arms and walked around asking everyone who your parents were. There were so many refugees arriving at the dharamshala every day!

Anyway, to come to the point, I visited Ajit recently. He continues to live in Calcutta, where my parents settled after Partition, and where we grew up.

Only a small percentage of the Sindhis evicted from Sindh settled in Calcutta. For my father in the tea-trading business, it seemed a logical choice, and his tea business flourished. In those days, Calcutta was Indias largest centre for tea trading and auctions, and the family prospered. Our parents ensured that we four siblings received an excellent education. Ashok, the eldest, is a respected civil engineer and consulted on the value of properties by government authorities and courts. His book Valuation Principles and Procedures is a scholarly work that bridges the theoretical and practical aspects of real-estate valuation.

Ajit, a year younger and the quintessential Sindhi entrepreneur, runs the Harvard House chain of schools. Both live in Calcutta. I chose to become an academic, and my sister Mira, the baby of the family, is now the eminent Bombay gynaecologist and obstetrician Dr Mira Raisinghaney, well known as a fertility expert.

I had taken the 6am flight from Mumbais Chhatrapati Shivaji airport and arrived at what I still thought of as Dum Dum in Kolkata, despite its glamorous reincarnation as Netaji Subhas Chandra International Airport, at around 9am. Ashok was away in the USA visiting his son, and Ajit picked me up. We reached Ajits Theatre Road residence and I decided to change, have breakfast and refresh myself with a short nap, as I had woken very early that morning. But hardly had I drunk a glass of water when Ajit marched into my room and enthusiastically announced, Come, come! We are going on a picnic!