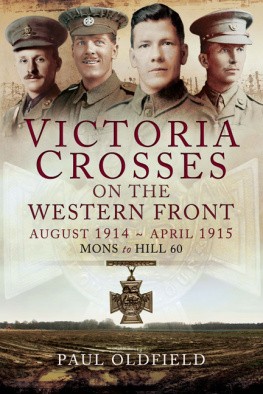

THE VICTORIA CROSSES THAT SAVED THE EMPIRE

The Story of the VCs of the Indian Mutiny

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS.

Copyright Brian Best, 2016

The right of Brian Best to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-47384-476-6

PDF ISBN: 978-1-47385-709-4

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-47385-707-0

PRC ISBN: 978-1-47385-708-7

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press

Typeset in 10/13 point Palatino

For more information on our books, please email: ,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Introduction

O n the morning of Friday, 26 June 1857, Britains largest military parade took place at the eastern end of Hyde Park. It was a perfect midsummers day with soaring temperatures as 9,000 troops and 100,000 spectators assembled to watch the first investiture of a new gallantry award named for, and presented by, Queen Victoria. Although the first eighty-five recipients had their citations published in The London Gazette on 24 February 1857, only sixty-two were present to receive their Victoria Crosses from the sovereign. It was her express wish to present her new gallantry award but not until later in the season, hence the long gap between announcement and presentation. At 9.30 a.m., the Queen, dressed in a specially-designed quasi-military riding habit, mounted her pony, Sunset. Accompanied by her husband Albert, dubbed that day as Prince Consort, along with her future son-in-law, Prince Frederick William of Prussia, and members of the Royal family and household, she rode up Constitution Hill and entered the Park through the gate at Hyde Park Corner. This moment was probably the high-water mark of Victorias reign with the Queen at her happiest and the country at ease with itself. For even as the Queen made the first presentations of the Victoria Cross to her Crimean heroes, dark shadows were appearing in a far off eastern country where many of the twenty-two absentees.

For the British, the Mutiny is a difficult period to contemplate, an odd mix of pride and shame, pity and anger. The pride derives from the courage and endurance of men who were faced with a harsh climate and a numerically superior enemy. The shame is engendered by the indiscriminate savagery meted out to not only the guilty, but the many innocent who could not possibly have been involved. The number of women and children who were slaughtered, bereaved or who endured starvation and disease warrants pity. The complacency, insensitivity and arrogance of the British administrators and officers who allowed the simmering discontent to boil over causes anger.

In fact, there had been mounting evidence of the Indian populations increasing discontent with the Honourable East India Company (HEIC). Originally a British joint-stock company formed to trade with the East Indies, it ended up trading mostly with the Indian subcontinent. The HEIC was one of the greatest commercial enterprises ever seen and, as it grew, it was allowed to have its own armies. Over a period of a century, three quite distinct armies came into being at different times and places. In chronological order these were the armies of the Presidencies of Bombay, Madras and Bengal, formed to protect the HEICs growing expansion throughout Indias interior.

As the decades passed, so the quality of British administrators and officers declined. Although John Companys profits slumped, there was still money to be made through corruption and nepotism. Lassitude and a growing contempt for the locals by second-rate white employers increasingly opened a void between the rulers and the ruled.

In December 1855, Lord Charles Canning, the new Governor-General of India, was prescient when he declared the following at a farewell dinner in London before he departed to take up his post: In the sky of India a small cloud may rise, at first no bigger than a mans hand but which may at last threaten to overwhelm us with ruin.

There had already been incidents of rebellion amongst some of the native regiments in the Bengal Army. It was an accumulation of grievances rather than a single event that triggered the outbreak in May 1857. The Bengal Army drew its recruits from higher castes as opposed to those in Bombay and Madras, who enlisted more localised and caste-neutral sepoys, as Indian soldiers were called. The domination of higher castes in the Bengal Army was one of the factors that led to the rebellion. There was a growing irritation that the Bengal Army was receiving special treatment as it was the only part of the Companys forces that refused to serve overseas. The General Service Enlistment Act of 1856 was passed to take soldiers out of India to places such as Persia, Burma and China. In the Bengal Army, only new recruits had to accept this commitment. The serving high-caste sepoys, however, saw this as the thin end of the wedge and added it to their list of grievances.

The Bengal Army further divided itself, with the infantry being Brahmins (high-caste Hindus) and Rajputs, while the cavalry, who lived apart, were, for the most part, Muslims. Promotion was extremely slow and based purely on time-served rather than talent. Another perceived threat was the increasing presence of British missionaries and chaplains, which led to fears of mass conversions to Christianity.

With all this resentment, it only took a rumour to spark the powder keg.

The Revolt of 1857 broke out over the new Enfield rifle and its ammunition: greased cartridges. Before loading the new percussion rifle, the sepoys had to bite off the end of the paper cartridge and ram it down the barrel. A rumour spread that the new paper cartridge was greased with cow and pig fat an anathema to both Hindus and Muslims. Too late, the cartridge was withdrawn and concessions were made, including allowing the sepoys to grease the cartridges themselves. But to no avail the British were still seen as attempting to defile the sepoys religions.

On 26 February 1857, the 19th Bengal Native Infantry (BNI) refused to take the cartridge. At Barrackpore, on 31 March, the 19th BNI was disbanded for open and defiant mutiny.

Two days before, a sepoy of the 34th BNI, Mungal Pande, had run amok while high on drugs, firing at a British officer and NCO before being arrested and hanged. The 34th was disbanded on 6 May but by that time it was apparent that the Bengal Army was on the verge of a major outbreak of rebellion. On Sunday, 10 May, at the military cantonment of Meerut, the dam finally burst.