Railroads Past & Present

H. ROGER GRANT AND THOMAS HOBACK, EDITORS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

2019 by H. Roger Grant

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grant, H. Roger, [date] author.

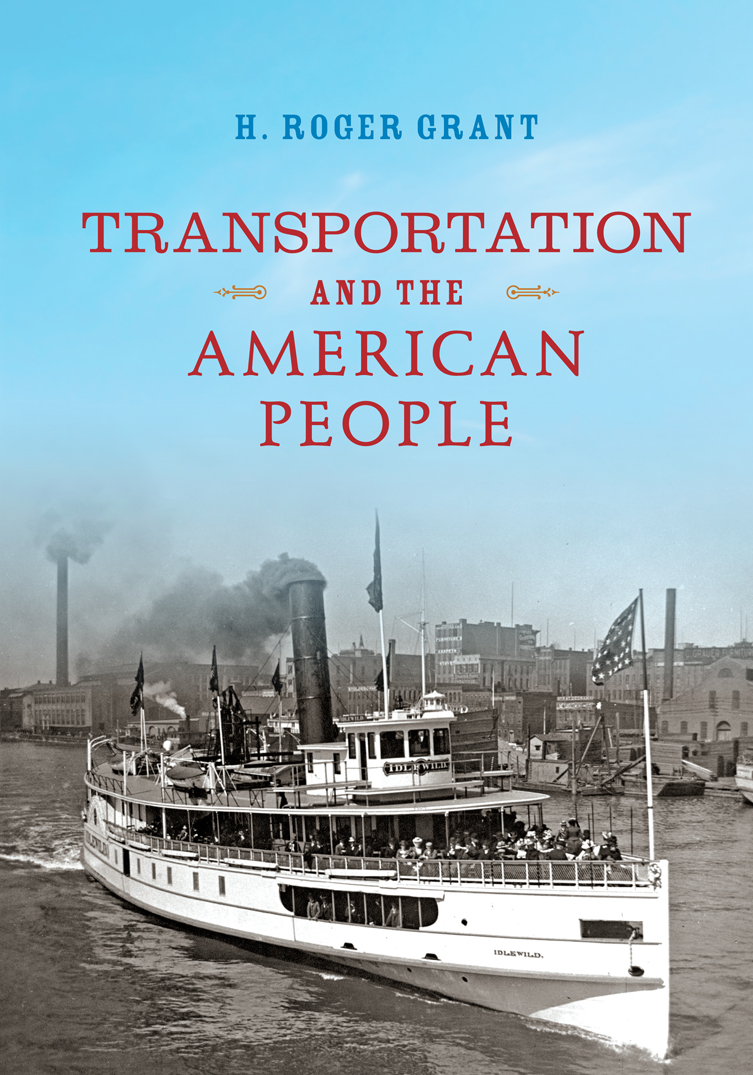

Title: Transportation and the American people / H. Roger Grant.

Description: Bloomington : Indiana University Press, [2019] | Series: Railroads past and present | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018049665 (print) | LCCN 2018051099 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253043344 (e-book) | ISBN 9780253043306 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: TransportationUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC HE203 (ebook) | LCC HE203 .G693 2019 (print) | DDC 388.0973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018049665

1 2 3 4 5 24 23 22 21 20 19

FOR MY BROTHER:

Richard D. Grant (19332004)

CONTENTS

Transportation and the American People is designed as the third book in my specialized social history series. The previous studies, both published by Indiana University Press, include Railroads and the American People (2012) and Electric Interurbans and the American People (2016). The present work partially came about because of what I saw as a void in the published literature. For years I have taught an upper-division undergraduate course on the history of American transportation, and early on I realized the need for a more inclusive and available work on the topic. Although there are studies that explore aspects of the social history of travel, none are comprehensive and up-to-date. Bus passengers, most of all, have been marginalized, having never been covered in any depth. Through its coverage of six commercial travel experiences, ranging from those on stagecoaches to airplanes, Transportation and the American People hopefully addresses these shortcomings.

A challenging dimension of writing the present volume involved its connection to my previous two works. Obviously, I cannot examine steam and electric interurban railways to the same degree here, needing in this study to reduce coverage and to provide fresh narrative materials. Those readers who wish for more specialized information on such topics as town building, regulatory reform, and railroaders personalities should consult these earlier books.

There is no question that historians of all types should pay more attention to the nonrailroad topics found in this study. It makes sense for further work to examine in greater detail the social history of airlines, buses, canals, stagecoaches, and waterways. Nor should we ignore noncommercial transport, including travel by foot, horseback, bicycle, motorcycle, and automobile. Each topic might easily become one or perhaps multiple full-length studies. Through additional research and by asking imaginative questions, a more comprehensive social history of American transportation can be achieved.

When one considers the sweep of the American experience, it becomes clear that the movement of people has been a vital and ongoing part of molding the national character. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner proposed his famed frontier hypothesis in 1893that American democracy was rooted in the frontierwhen he saw correctly that mobility contributed to such recognizable traits as individualism, materialism, nationalism, and optimism, as well as democratic thought.

As with every book project, there are individuals and institutions to acknowledge that have made contributions. Various contacts that I have made through my longtime association with members of the Lexington Group in Transportation History have allowed me to tap the insights of knowledgeable people and have provided suggestions for source materials. One person stands out: John (Jack) W. White Jr., former curator of transportation at the Smithsonian Institution. Even though recovering from a stroke, he kindly commented on several chapters of the manuscript. Others, too, have assisted, notably William (Bill) Howes and Art Peterson. Kay Crocker, IT specialist at Clemson University, repeatedly gave me much-needed technical support, and Alan Burns likewise aided with production. A variety of institutions have helped. These include the Booth Western Art Museum, Cartersville, Georgia; Main Street Blytheville, Blytheville, Arkansas; Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis; Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Library of Virginia, Richmond; Mercantile Library at the University of MissouriSaint Louis; Minnesota Discovery Center, Chisholm, Minnesota; Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, Toledo, Ohio; Wells Fargo Museum, San Francisco; and the Clemson interlibrary loan department. Once again I have received continued support from the talented and dedicated staff of Indiana University Press.

Since 2006 I have benefited from being the Kathryn and Calhoun Lemon Professor of History at Clemson. This academic chair has provided research funds and allowed for a reduced teaching load, just as it aided with my two previous social history works in this three-part series, Railroads and the American People and Electric Interurbans and the American People.

As with more than thirty previous academic books, my wife, Martha Farrington Grant, read the manuscript and made valuable suggestions, which is devotion above and beyond our marriage contract that we made in 1966.

STAGECOACH NETWORKS

From colonial times until the steam-car civilization took hold with the coming of the Gilded Age, the stagecoach was often the primary form of commercial domestic travel and essential where water options were unavailable. Stagecoaches were the symbol of rapid transportation in 1815, observed economic historian George Rogers Taylor. Though coastwise voyages were less expensive and certainly more comfortable, travelers in a hurry took the stages, whose speed was being considerably increased as a result of the rapid spread of turnpikes. On poor roads and trails, coaches were slower than most river, coastal, and lake vessels. But compared with trips on the nations emerging network of canal packets, stagecoaches usually traveled at speeds that were two, three, or more times greater. Time certainly mattered, but there was widespread agreement among patrons that the stagecoach was frequently an uncomfortable form of public transportation, most of all when they were riding overnight.