JOHN

EVELYN

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Series Editor: Franois Quiviger

Already published

Blaise Pascal: Miracles and Reason Mary Ann Caws

Caravaggio and the Creation of Modernity Troy Thomas

Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares Nils Bttner

John Evelyn: A Life of Domesticity John Dixon Hunt

Michelangelo and the Viewer in His Time Bernadine Barnes

Petrarch: Everywhere a Wanderer Christopher S. Celenza

Rembrandts Holland Larry Silver

JOHN EVELYN

A Life of

Domesticity

JOHN DIXON HUNT

REAKTION BOOKS

For Jo Joslyn and Alan Choate

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2017

Copyright John Dixon Hunt 2017

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 978 1 78023 870 8

COVER: Studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller (16461723), John Evelyn, n.d., oil on canvas. Whereabouts unknown (sold at Sothebys, London, 1993) photo Sothebys/akg-images.

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

Celebration

Mavis Batey, ed., A Celebration of John Evelyn: Proceedings to Mark the Tercentenary of his Death (Goldalming, 2007)

Correspondence

Diary and Correspondence of John Evelyn, ed. William Bray, 4 vols (London, 1857), vol. III

Darley, John Evelyn

Gillian Darley, John Evelyn: Living for Ingenuity (New Haven, CT, and London, 2006)

Diary

The Diary of John Evelyn, ed. E. S. de Beer, 6 vols (Oxford, 1955)

EB

Elysium Britannicum; or, the Royal Gardens, ed. John E. Ingram (Philadelphia, PA, 2000)

Evelyn DO

Therese OMalley and Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn, eds, John Evelyns Elysium Britannicum and European Gardening (Washington, DC, and Dumbarton Oaks, 1998)

Keynes, Bibliophily

Geoffrey Keynes, ed., John Evelyn: A Study in Bibliophily (2nd edn, Oxford, 1968)

LB

The Letterbooks of John Evelyn, ed. Douglas Chambers and David Galbraith, 2 vols (Toronto, 2014). Pagination continues throughout the two volumes

Memories

Geoffrey Keynes, ed., Memories for my Grand-son (London, 1926)

MW

Miscellaneous Writings, ed. William Upcott (1825)

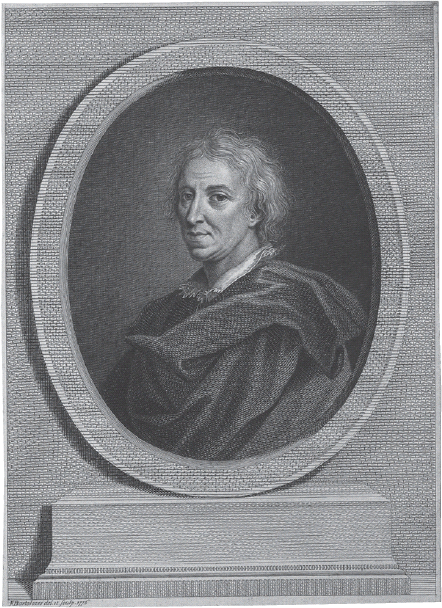

1 Francesco Bartolozzi, John Evelyn, 1776, engraving.

Introduction

Happy the man who lived content

With his own Home and Continent.

EVELYN AFTER CLAUDIAN

To know men one must isolate them. But after a long experience, it seems right to put back such isolated reflections into a relationship.

RILKE, TRANS. WILL STONE

M OST PEOPLE HAVE HEARD of John Evelyn, but he is far less known for either his writings or his life. He was a private man, yet always wished for responsibility within a larger and, during his lifetime, troubled England. His Diary, published in a modern annotated edition, tells us much about his public life, little about his private one. The diary of his friend Samuel Pepys is more widely used, more fun, and more in tune with what we assume were the mores of the Restoration: intimate, gossipy, occasionally racy. Little of Evelyns considerable writing is available, but much of it is intriguing; yet it has to be found mostly in collections of rare books. He wrote about urban planning, fashion, London weather or what we would call climate change (and that small book has been reissued in modern times). For those in the know he was an accomplished gardener and a specialist on trees. He is, then, if not wholly unnoticed, not really known.

Yet he was somebody to be reckoned with during a heroic period of English intellectual culture. He was a devoted follower of Francis Bacon and applied that masters rigour to a wide range of ideas and materials, augmenting much of the Baconian agenda. As a young man he travelled widely in Europe, attended carefully to everything he saw, found important books to translate for English readers, became an accomplished, if somewhat withdrawn and modest, personage around the court, was a prominent member of the newly formed Royal Society, and knew some of the most exciting virtuosi and scientists of his age (Christopher Wren, Robert Hooke, Wenceslaus Hollar, Robert Boyle); he also advised his contemporaries on the two matters that always mattered most to him gardening, arboriculture and their role in a new and Enlightened England. Yet his monumental manuscript on gardening was only transcribed and published in 2000, while the garden he created at Sayes Court in Deptford no longer exists; the wonderful tree book, Sylva, went through so many editions, and confusingly changed its title to Silva, so that his concern with arboriculture has perhaps lost its edge today.

He also lived through one of the most troubled times that England ever encountered (until the Great War in the twentieth century), with a king executed, a failed republican experiment, military dictatorships, forms of religious belief and practice challenged and changed, another king banished for trying to govern autocratically, to be replaced with a foreign statesman from the Netherlands, confronting wars in Europe, and a developing colony in North America, all driven by and driving a profoundly transformed economy. He found himself living and sometimes serving under five monarchs, yet all the while keeping both his own counsel and a level head, and a firm conviction that his faith in the Church of England and in the probity and usefulness of family life mattered above everything else.

While he was a person who focused upon his family, he also sought to play a role in an England that, once the Commonwealth was abandoned and the monarchy resumed in 1660, was to be a community of promise. He wrote that he was content to exist in his own home and continent, but that inclination saw him travelling widely and at length in Europe as a young man. On his return, he nourished ambitions within the state and culture of England to bring home ideas that he encountered abroad, translating important foreign works that he wanted his contemporaries to read, and raising an awareness of European building, town planning and landscape architecture. He worked outward from his own enthusiasms, his own commitments, not wholly given over to a full participation in a country where he found both religion and politics sometimes uncongenial. Yet he also recognized how much he wanted to put his own individual experience into fruitful contact with his contemporaries, for he himself knew that in the late seventeenth century isolation was not an option, though many others did take that path.

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.

Books in the RENAISSANCE LIVES series explore and illustrate the life histories and achievements of significant artists, intellectuals and scientists in the early modern world. They delve into literature, philosophy, the history of art, science and natural history and cover narratives of exploration, statecraft and technology.