University of Nevada Press | Reno, Nevada 89557 USA

www.unpress.nevada.edu

Copyright 2017 by University of Nevada Press

All rights reserved

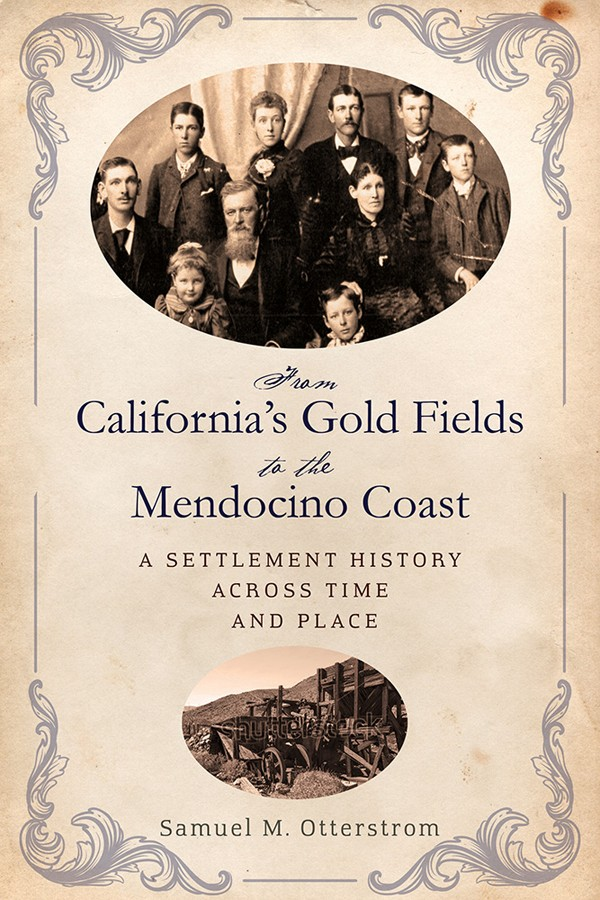

Cover design by Rebecca Lown

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Otterstrom, Samuel, author.

Title: From Californias gold fields to the Mendocino Coast : a settlement history across time and place / Samuel M. Otterstrom.

Description: First edition. | Reno : University of Nevada Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016054335 (print) | LCCN 2016055116 (e-book) | ISBN 978-1-943859-28-3 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-0-87417-469-4 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: California, NorthernDiscovery and exploration. | California, NorthernHistory19th century. | Frontier and pioneer lifeCalifornia, Northern. | Land settlementCalifornia, NorthernHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC F867.5 .O78 2017 (print) | LCC F867.5 (ebook) | DDC 979.4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016054335

Manufactured in the United States of America

1

The Scales of California Settlement History

New Hope is an optimistic place name, and hope and optimism likely pervaded the thoughts of the approximately 230 Mormons who sailed with Samuel Brannan from New York to California on the ship Brooklyn, arriving in Yerba Buena (San Francisco) July 31, 1846. About twelve families moved on to the Stanislaus River to establish a new community in anticipation that many Mormons would follow them there (J. Davies 1984, 810). Despite its name, New Hope Colony did not last very long. The bulk of the Mormons never came to settle in California but instead stopped in the valley of the Great Salt Lake.

By the time the announcement of gold in the Sierra Nevada had become public in 1848, New Hope was gone. Its demise was assured by the colonys poor location (plagued by mosquitoes and malaria), conflict with Sam Brannan, and the news that the main body of Mormons was not coming to California (Owens 2004, 4748). In contrast, the Mormons who remained in Yerba Buena found more economic success as the peninsula was poised to grow, due to the event soon to occur in the Sierra foothills to the east (Stellman 1953, 6465).

The great new hope for the future growth of the newly U.S. California began at an obscure place, Sutters Mill, that did not fade from the map as New Hope Colony had done. Incidentally, it too had a Mormon presence. John Sutter, needing laborers to build his sawmill on the banks of the American River, hired a number of Mormons (formerly of the Mormon Battalion) who had traveled together to California to fight in the Mexican-American war. They fought no battles, because the war had already ended by the time they arrived in San Diego on January 29, 1847 (J. Davies 1984, 6). Many of these Mormons decided to stay in California for a time to work, and at least five hired on at Sutters Mill. They were on the job when James Marshall discovered gold in the tailrace at the mill site in January of 1848, and two of them recorded some of the earliest accounts of the discovery in their personal writings.

Regardless, instead of a new hope emanating from an agricultural colony in the San Joaquin valley, it sounded with a thunderous clap from the small sawmill at Coloma, recorded and expanded along the river by Mormon laborers. In San Francisco, Samuel Brannan promoted and advertised the discovery with verve, for he stood ready to make his transitory millions through the newspaper business and by selling supplies to the miners who soon would come. Brannans mercurial rise and fall is one of the great stories of early California history.

But for every Sutter, Marshall, and Brannan, there were thousands of relatively unknown characters who also made their mark on the promising California landscape. Most of their movements are lost to history, but dependence and interaction between the mines in the Sierra Nevada foothills and the San Francisco Bay area were ongoing and significant. One Mary Ann Fisher Cheney, a Mormon immigrant who arrived on the Brooklyn, wrote in 1850 of how she and her husband panned for gold in the Sierra and raised produce on their farm at San Jose. She noted that over the winter of 18491850, they were able to sell a dozen eggs for the incredibly high price of $6. These exorbitant prices did not last long, as farming was suddenly a very attractive option for the forty-niners and other immigrants (Owens 2004, 25354). Mary Cheney and her husband are just two examples of the thousands of people who arrived to the valleys blossom with produce and livestock, to provoke the rivers and streams to give forth their riches, or both. Thus, the symbiotic cycle between the mountains and valleys of California was established. More importantly, it was often the lot of successful or discouraged miners alike to be integrally connected with the economic development and spatial dependency that ensued because of the monetary courses they took.

PEOPLING OF CALIFORNIA ACROSS TIME AND SPACE

This region of California certainly has a story to tell. The story is hidden beneath a wave of untold numbers of gold miners, merchants, farmers, politicians, carpenters, and ever more people from various backgrounds and corners of the world. Amidst this mass of historical data is an intricately woven tapestry of interrelated people and events that literally created this dynamic state. At its most basic level, northern California can be geohistorically dissected into composite elements of individual persons acting in their defined portions of the landscape at a particular point of time. Very quickly, study at this individual level requires an agglomeration of individuals, first in family units, next in small communities or neighborhoods, followed by counties or cities, and finally a regional system. Just as in the human body, where no one atom or cell can act individually without affecting its surrounding elements, the history of nations has been written and shaped both by the most incongruous farmer and the exceptionally boisterous politician.

This book explores the lives of the many people who made the valleys of California bloom within a wide variety of human landscapes. Dozens of excellent books have been written concerning the early growth and development of the state, from sweeping comprehensive histories (Bean and Rawls 1983; Brands 2002; Lavender 1972; Roske 1968; Starr 1973) to regionalized and geographically focused monographs (Brechin 1999; Fradkin 1995; Hardwick and Holtgrieve 1996; Holliday 1999; Lotchin 1974). This book adds a particular perspective to that large and competent body of literature. It illustrates how the new settlers initial land-altering presence persisted over time through their family relationships, and how the early pioneers and miners periodically transformed themselves in response to constantly shifting economic paradigms. By multiplying these individualistic experiences across the far-flung reaches of the California system into larger and larger scales, this book uncovers the secrets that propelled a sleepy postMexican outpost into a flurry of restless, youthful growth, which has continued virtually unchecked until today.

As the unending throng of people pushed into California beginning in late 1848 and early 1849 and throngs surging into the next several years, they changed the region forever. Their impact on the rivers and forested slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountain foothills was significant, but most of the players in this drama were like the butterflies that cover the hillsides in the fairer months but disappear in the winter. The miners were constantly on the lookout for better diggings in other sparkling streams in other valleys, and so permanence of address was not common. This seething, never-resting mass of opportunistic argonauts often made its most lasting impacts in the cities and farms of other parts of the state after individual luck ran out, or when people became tired of the uncomfortable life of a miner. San Francisco and Sacramento would likely have not grown so spectacularly were it not for the immigrants and the businesses associated with mining. In this way, all of northern California was intertwined and interrelated in the nearly living regional organism that matured into an economically innovative and increasingly dynamic spatial system (fig. 1.1).