2011 by Anthony M. Platt.

Preface to the new edition 2021 by Anthony M. Platt.

All rights reserved. No portion of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from Heyday.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Platt, Tony, 1942- author.

Title: Grave matters : the controversy over excavating Californias buried Indigenous past / Tony Platt.

Description: New edition. | Berkeley, California : Heyday, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021025728 | ISBN 9781597145596 (paperback) | ISBN 9781597145626 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Yurok Indians--California--Big Lagoon--Antiquities. | Yurok Indians--Funeral customs and rites--California--Big Lagoon. | Yurok Indians--California--Big Lagoon--Government relations. | Human remains (Archaeology)--Moral and ethical aspects--California--Big Lagoon. | Grave goods--Moral and ethical aspects--California--Big Lagoon. | Archaeologists--Professional ethics--California--Big Lagoon. | Cultural property--Protection--California--Big Lagoon. | Big Lagoon (Calif.)--Antiquities. | Big Lagoon Rancheria, California--Antiquities.

Classification: LCC E99.Y97 P57 2021 | DDC 979.4/12--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021025728

Cover Photo: Martin Swett

Cover Design: Ashley Ingram

Interior Design/Typesetting: Lorraine Rath

Published by Heyday

P.O. Box 9145, Berkeley, California 94709

(510) 549-3564

heydaybooks.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In the summer of 2006 my forty-year-old son died. Daniel left a clear written message that he wanted a funeral at Big Lagoon, the northwestern California village on the coast where we have a vacation cabin. We honored his request, sending his ashy remains off into the lagoon. Some eighteen months later I discovered that the Yurok who lived in this area since time immemorial had been buried a few hundred yards away from my cabin. But unlike Daniels, their remains were prey to looters, archaeologists, and collectors, and their lives and deaths scrupulously forgotten in the regions public history. Since this discovery I have felt compelled to remember them as well as I remember my son. This book is dedicated to their remembrance.

We cannot conceive of a time when stabilizing the world will become an irrelevant act.

Julian Lang, Karuk, 1991

We tell stories of events to allude to the unspeakable.

Kara Walker, 2006

The meeting of sea and continent, like the meeting of whites and Indians, creates as well as destroys. Contact was not a battle of primal forces in which only one could survive. Something new could appear.

Richard White, The Middle Ground

Who does not seek to be remembered? Memory is Master of Death, the chink in his armor of conceit.

Wole Soyinka, Death and the Kings Horseman

People who have learned how to care tenderly for the bodies of the dead are almost surely people who also know how to show mercy to the bodies of the living.

Thomas G. Long, 2009

Know

that I want to sleep here amid the eyelids

of sea and earth.

I want to be swept

down in the rains that the wild

sea wind assails and shatters

and then to flow through subterranean channels,

toward the deep springtime thats reborn.

Pablo Neruda, Canto General, Dispositions

Preface to the New Edition

More than a decade ago, a sudden personal tragedy and a gradual awareness of a social tragedy impelled me to write Grave Matters.

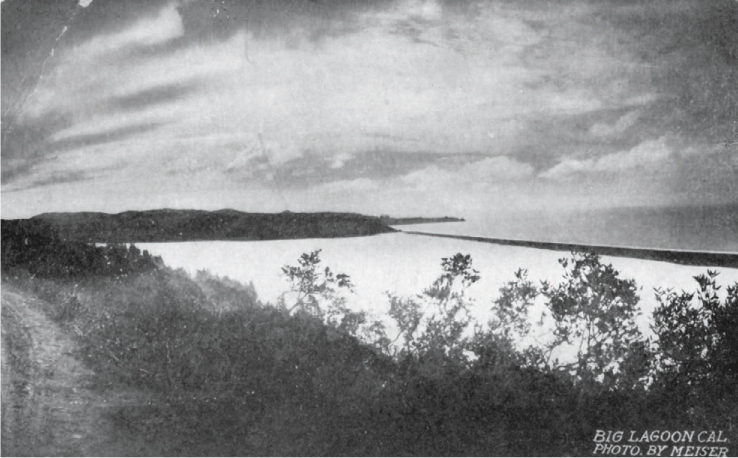

Two places, one rural and one urban, figure prominently in the story: Big Lagoon, a park and residential village in Humboldt County that abuts the fierce Pacific Ocean, a tranquil lagoon, and remnants of old-growth forests; and Berkeley, home since 1873 to the first campus of the University of California. I have shared a cabin in Big Lagoon since the mid-1970s, and I have lived and worked in Berkeley for some fifty-seven years since I came here as an immigrant from England in 1963, planning to stay for a year of study but never leaving. The Free Speech Movement and Berkeleys progressive politics changed my mind and shaped my future.

As an activist and academic, my intellectual work prior to this book focused on the history of the American carceral state, with an emphasis on race. Then, Native* and California histories were peripheral to my expertise and curiosity. My sons death in 2006 and his request to be buried in Big Lagoon triggered my interest in funerary rituals. It turned out, serendipitously, that how we memorialized our son by launching his ashy remains into the lagoon echoed how the local Yurok had imagined their ancestors traveling through a river into the underworld. This connection meant and still means a great deal to me.

A year after our personal memorial service, the Yurok Tribe passed a resolution calling for the protection, preservation, and cultural management of O-pyweg (Where They Dance or Big Lagoon), a place of ceremonial renown that had been an important Native settlement prior to the genocidal devastation of peoples who had lived in this region since time immemorial. They were well established here long before a Spanish naval expedition planted its flag on top of a nearby hill; long before fortune-hunters passed by on their way to the gold mines; long before homesteaders tried to farm the rugged landscape and fish the turbulent coast; long before lumber companies extracted and marketed ancient redwoods for everything from construction materials to decorative doodads; and long before the northwest coast of California became a post-industrial bucolic retreat for people like me wanting relief from the metropolis.

In March 2009, I participated in the Yurok-led Coalition to Protect Yurok Cultural Legacies at O-pyweg. Despite tensions between defenders of individual property rights and Native advocates of communal patrimony, the coalition of disparate stakeholders worked together to successfully lobby the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors to support, at least in principle, measures to acknowledge and secure Where They Dance. It was while working with the coalition that I discovered how, in the early twentieth century, amateur archaeologists, collectors, and tourists had excavated the main village site at Big Lagoon and removed skeletons, funerary offerings, and artifacts. This happened throughout the region in the wake of the Gold Rush, genocide, and land dispossession.

Yurok elders know this history in sorrowful detail. Some remember stories passed on by their grandparents. They also introduced me to the long history of Native resistance to the widespread plunder of graves and appropriation of cultural artifacts: from respectful petitions to authorities, to the rambunctious militancy of the Red Power movement. In northern California, the intertribal Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association (NICPA), founded in 1970, physically confronted amateur and professional archaeologists and put a stop to unauthorized excavations, setting a precedent for national legislation some twenty years later.