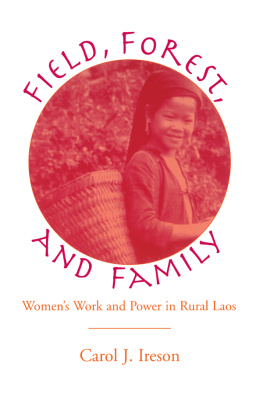

Field, Forest, and Family

First published 1996 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ireson, Carol J.

Field, forest, and family : womens work and power in rural Laos /

by Carol J. Ireson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8133-8936-4 (hardcover) ISBN 0-8133-3730-5 (paperback)

1. Women, HmongSocial conditions. 2. Women, LaoSocial

conditions. 3. Women, KhmuSocial conditions. 4. Sex role

LaosLouangphrabang (Province) 5. Social changeLaosLouangphrabang

(Province) 6. Louangphrabang (Laos : Province)Social conditions.

7. Louangphrabang (Laos : Province)Economic conditions.

I. Title

DS555.45.M5I74 1996

305.409594dc20

97-27143

CIP

All photos by Carol and Randy Ireson. Editing by Virginia Bothun, Randy Ireson, and Helen Takeiuchi. Typesetting by Elsa Struble and Layla George. Indexing by Anthony Lafrenz of Catchword, Inc.

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-3730-2 (pbk)

To my parents,

Eddie and Barbara Jean Doolittle

Field, Forest , and Family is the culmination of work in Laos ranging over more than a quarter of a century of my life. My research and experience in Laos form the basis for much of the book, though I rely more heavily on existing literature for Khmu and Hmong comparisons and I draw liberally on other published and unpublished sources when relevant. I gathered the information about rural women from several years of development project work in Laos. In all I have worked in Laos for five years (196769, 198486, 198889) and have made several shorter visits. I was fortunate to be able to travel and carry out research in Laos during these times. Foreigners not from socialist bloc countries were rarely granted permission by communist government authorities to travel to rural areas for research purposes alone. Thus, data on the social and economic impacts of events like agricultural cooperativization, economic liberalization, or the removal of restrictions on family planning education and birth-control devices have usually been gathered by foreigners primarily in the context of development project planning, implementation, and evaluation. Furthermore, there were no Laotian social science researchers who were carrying out research during the time periods covered in this book.

I first worked in Laos in the late 1960s as a volunteer on the rural development team of International Voluntary Services (IVS). At that time I learned to speak Lao and became acquainted with Lao culture and customs. In 196869 I designed and, with the support of the Royal Lao Government and the United States Agency for International Development, implemented a study of the diet of twelve families in each of six villages from northern to southern Laos. War interfered with the study, but my six research teams (home economists from the Ministry of Agriculture and their counterpart IVS home economists) were able to interview household members and to record and weigh the food prepared over a three-day period during at least two of the three seasons in most selected village households. With the help of a nutritionist from the World Health Organization (WHO), research teams also weighed and measured children in these households, noting obvious signs of nutritional deficiencies (C. Ireson 1969). Some of this information is included in .

); and me.

I have augmented these data with information gathered from a 1989 interview study, sponsored by the Forestry Department of the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Forestry and funded by the Swedish International Development Authority, of 200 women in Bolikhamsay Province. The research team randomly selected 120 women farmer/gatherers, ages 20 to 55, from eight villages and 80 women residents of two timber company towns for 40 to 60 minute interviews. Most respondents were ethnic Lao. Villages were of two types: villages with access to mature forest and villages with access only to degraded forest. Survey villages ranged in size from 35 to 160 households, .

In addition to these studies, I draw on interviews with Lao refugees to the United States. The study, Patterns of Cooperation in Rural Laos, was carried out with funding from the Social Science Research Council under the Indochina Studies Program, a program specifically oriented toward culture-saving. The program supported research projects that documented pre-1975 Indochinese cultural patterns and artifacts, using recent refugees from Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam as cultural informants and sources of information. At that time, all three countries were nearly completely closed to Western researchers. Patterns of Cooperation in Rural Laos was organized by Carol and Randall Ireson, with the collaboration of four Lao-American social service professionals: Kham-One Keopraseuth, Chansouk Meksavanh, Tou Meksavanh, and Chareundi Vansi (1988). All four were born and raised in Lao villages during their early years, though all left the countryside to continue their education.

The study draws on semi-structured interviews of 40 ethnic Lao adult informants (21 men, 19 women) who lived in a Lao village for at least part of their adulthood, actively participating in traditional village life. The informant pool included former villagers from northern (n=5), central (n=14), and southern (n=21) provinces. Interviews were conducted in Lao, usually by two team members, and covered a standard list of topics. Interviews lasted from forty-five minutes to three hours, with shorter follow-up interviews of a few informants. The sections of the recorded interviews pertaining to village work were transcribed into Lao and translated into English. Taped interviews, Lao transcriptions, and English translations are archived in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., in the study Traditional Cooperation Patterns in Rural Laos. These data include information about ethnic Lao womens work before 1975.

I also draw from other development project experience of my own, from government statistics, and from the mainly unpublished development and aid agency reports of others. Since 1984, I have been gathering relevant information from Lao government ministries, the National Womens Union, foreign aid agencies working in Laos, and from local officials and villagers.

For example, one study I discuss was carried out by the Lao government with the support of the Commission of the European Communities. This study included seven villages in an area 15 kilometers southwest of Luang Prabang town. The villages were selected for participation in a variety of rural micro-projects (Luang Prabang Rural Micro-Projects 1990, 1991). Another included study was undertaken by the Swedish International Development Authority in conjunction with their upland agriculture project in the province and contains information from nine villages in two southern districts of the provinceLuang Prabang and Muang Nan (see .