University of Virginia Press

2018 by John A. Hodgson

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2018

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hodgson, John A., 1945 author.

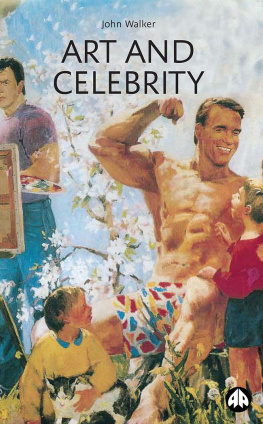

Title: Richard Potter : Americas first black celebrity / John A. Hodgson.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017030696 | ISBN 9780813941042 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813941059 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Potter, Richard, 17831835. | MagiciansUnited StatesBiography. | African American magiciansUnited StatesBiography. | African American entertainersBiography. | EntertainersUnited StatesBiography. | VentriloquistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC GV1545.P65 H63 2018 | DDC 793.8092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030696

Cover art: From Rannie broadside, 1810, Nefi cos Box advertisement.

(Courtesy of the New Bedford Whaling Museum)

Foreword

Its no sleight of hand to say that John Hodgson has written the definitive biography of the pioneering African American ventriloquist Richard Potter (17831835). It is a fact, whose timeat long lasthas come. After all, Richard Potter came of age in the early years of the American republic, when the Founding Fathers walked the earth, and his travels took him to both sides of the Atlantic at a time when the notion of celebrity in the popular imagination was at a formative stage. One of the most captivating personalities in the history of his craft, Potter was, and remains, essential to the longer African American journey, yet his story has too easily been obscuredand misconstrued. With the publication of his pathbreaking book Richard Potter: Americas First Black Celebrity, John Hodgson has, through painstaking research, helped to set the record straight on his subjects remarkable life and adventures. In doing so, he also treats readers to a fascinating look at the history of ventriloquism in early America.

A few quick, amazing facts about Richard Potter: he was born in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, in 1783, the last year of the American Revolution. Although the Commonwealth of Massachusetts would not officially outlaw the slave trade until 1788, emancipation was in the air and in the courts. The slaves Mum Bett (Elizabeth Freeman) and Quock Walker were suing for freedom under the states new constitution, which stated, All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and unalienable rights.

Those rights didnt magically appear, and they could be stolena reality that Potters mother, Black Dinah, may have known firsthand. Dinah Swain was kidnapped during her childhood in Guinea. By her own account, she was poisoned by her captors with a lump of sugar dipped in rum. She was then brought to New England, where she became a slave of Sir Charles Henry Frankland, a tax collector for the Port of Boston. Richard was born to Dinah fifteen years after Frankland died in England, leaving his wifeand, later, son Henryto manage the familys Massachusetts estate. Richards father was a local white man named George Stimson, making Potters surname a mystery.

One of six or possibly seven children, Potter appears to have received some schooling in Hopkinton before the age of ten. Some accounts state that he then sailed to Europe as a cabin boy and arrived in England, where he was enthralled by a Scottish magician and ventriloquist, John Rannie. As Hodgson suggests, Potter traveled to Europe around the age of sixteen, and began his career as an acrobat there, but did not meet John Rannie and his older brother James in Europe.

Potter returned to North America around 1803 and was back in Boston by 1807. In the interim he had begun apprenticing with John and then James Rannie and had acquired expertise as a magician and ventriloquist. The following year he married Sally Harris. They had two sons and a daughter; their first child, Henry, was killed in a wagon accident in 1816. When at home in Boston in those early years, Potter worked briefly for the family of the Rev. Daniel Oliver, and he honed his craft by entertaining the children around the fire. In 1810 James Rannie decided it was time to hang up his cloak and retire from public life to tend to the large tract of land he had acquired. When he did, he left his former apprentice with a virtual lock on the U.S. market. Potter wasted little time staking out his claim.

Thankfully, a few broadsides for his engagements were preserved. One of these (circa 1811), adorned with the Masonic symbol and a woodcut of a man communing with birds, previewed the show Potter would perform at a local ballroom. His stated purpose: to give an Evenings Brush to Sweep away care. The first part of Potters act would feature his magic, with 100 curious but mysterious experiments with cards, eggs, money, &c. In the second part of the show, the ad stated, Mr. P. will display his wonderful but laborious powers of Ventriloquism. He throws his voice into many different parts of the room, and into the gentlemens hats, trunks, &c. Imitates all kinds of Birds and Beasts, so that few or none will be able to distinguish his imitations from the reality. This part of the performance has never failed of exciting the surprise of the learned and well informed, as the conveyance of sounds is allowed to be one of the greatest curiosities of nature. Potter also performed what was known as a Man Salamander act for a few years, handling a red-hot bar of iron and immersing his feet in molten lead.

Its a wonder that Potter, throughout his career, seems to have steered clear of white Americas fears that black magic lurked behind various slave revolts in their midst. For example, despite fears of a black conspiracy when a black man allegedly set fire to a Boston ship in 1817, Potter remained unscathed. Perhaps aware of his audiences perceptions of otherness and identity, Potter, early in his career, advertised himself as West Indian, and he later passed as white when touring in the South. Some accounts identified him as colored in the latter part of his career. This is one of the many important revelations in Hodgsons investigative biography.

Wherever Potter was, whatever he appeared to be, he exploited his otherness to add an allure to his fame. In this way, he prefigured such black performers as the fugitive slave Henry Box Brown and the great African American ventriloquist of the twentieth century John W. Cooper (18731966). Richard Potter died at age fifty-two on 20 September 1835, exactly 145 years before the fictional Harry Potter was born (1980, if you do the math in the Rowling books), and 39 years before that other famous Harry, Houdini, was born in Budapest, Hungary. Potter was buried in Potter Place, New Hampshire, under the headstone transcribed by the nineteenth-century black historian and abolitionist William Cooper Nell: In Memory of / RICHARD POTTER, / The Celebrated VENTRILOQUIST, / Who died / Sept. 20, 1835, / Aged 52 years.

Now, in Hodgsons brilliant biography, Potter is brought back to life through the scholarly arts of careful research and reasoned judgment. Richard Potter: Americas First Black Celebrity is a most wonderful study, and I commend readers to read it as if sitting in the audience of one of Potters earliest stage shows. The thrill I felt in reading Hodgsons bookand, through it, discovering Richard Potter, the man and his timeswas, in a word,