Copyright 1982, 1992, 2004 by Schocken Books

Foreword 2004 by Mary Clearman Blew

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover and in paperback in 1982 and subsequently published in paperback in 1992 with revisions by Schocken Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Womens diaries of the westward journey.

Bibliography: .

1. Overland Journeys to the PacificSources.

2. WomenWest (U.S.)History19th centurySources.

3. West (U.S.)History18481950Sources.

I. Schlissel, Lillian. II. Series.

F593.W65 978.02 8054143 AACR2

eISBN: 978-0-307-80317-7

www.schocken.com

v3.1

To my mother, Mae Fischer,

and to my children, Rebecca and Daniel,

who will have roads of their own to travel

CONTENTS

LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS

Pioneer life

Emigrants in Echo Canyon, Neb.

Gathering supplies in Manhattan, Kansas

Mormon emigrants at South Pass

Margaret Hereford Wilson

Nancy Kelsey

Nancy Welch

Martha Morrison Minto, husband John, son

Catherine Sager Pringle

Nancy H. Snow Bogart

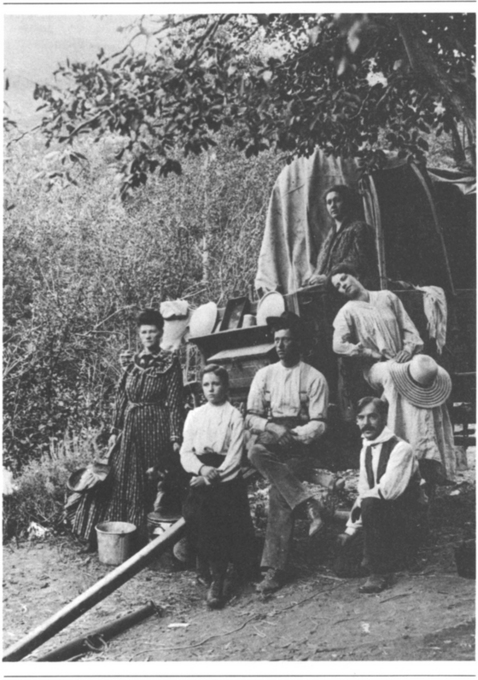

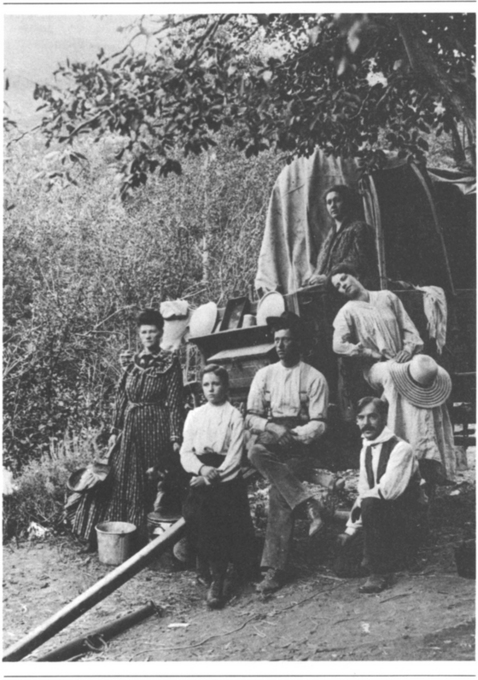

Overland family and wagon

Sarah Helmick

Lucy Henderson Deady

Mary Jane Megquier

Two matrons in Helena, Montana

Girl with donkey

Olive Oatman

Cecilia McMillen Adams, Dr. Adams

Wagon train, woman cooking over open fire

Free county school

Indian woman, Lady Oscharwasha, Rogue River, Ore.

Chores on the ranch, Colorado

Two girls, daughters of Joseph Suppiger, Illinois

Agnes Stewart

Elizabeth, Fred Warner

Charlotte Emily Stearns Pengra

Emigrant train crossing river

Lucy Brown Smith

Maria Parsons Belshaw

Roxana Cheney Foster

Helen M. Carpenter

Man with dead child

Death portrait of child

Harvey Andrews family at grave

Emily Butler in Jacksonville, Ore.

Clara Brown

Biddy Mason (two pictures)

Covered wagon arriving in Baker City, Ore.

Inez Adams Parker

Hager family

Woman homesteader

Map

Page of Haun diary

Settlers at toll road, Oregon

Amelia Stewart Knight

Gould family

Tourtillott family

Little girl in costume

ON PHOTOGRAPHY

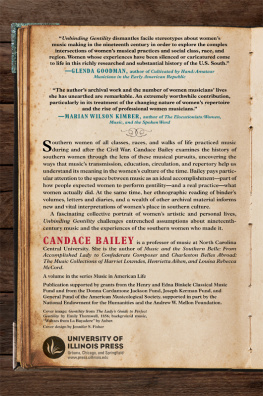

The invention of photography exerted a profound influence on American society. By 1845, daguerrotypy had become a popular enterprise, with studios in almost every major city. Quite apart from the pure wonder of the image, Americans who moved about restlessly felt a profound need to carry along some souvenir of loved ones they had left behind. The son who had gone off to the gold rush, the daughter who had married and gone to live in a distant territory, the child who had died before it learned to walksuch portraits were the priceless possessions of all classes of Americans.

Nowhere more than on the frontier were photographs so passionately prized. Pleas for family pictures filled the letters of those who found themselves in Oregon and California. As soon as photographers could be found, emigrants had formal pictures taken to send back home. Candid pictures were rare; studio photographs were more common, and many of the photographs of women in this book were taken years after the overland journey. These women were posing for their own families and for kinfolk back home, showing how they had prospered in the western lands.

I write on my lap with the wind rocking the wagon.

Algeline Ashley

FOREWORD

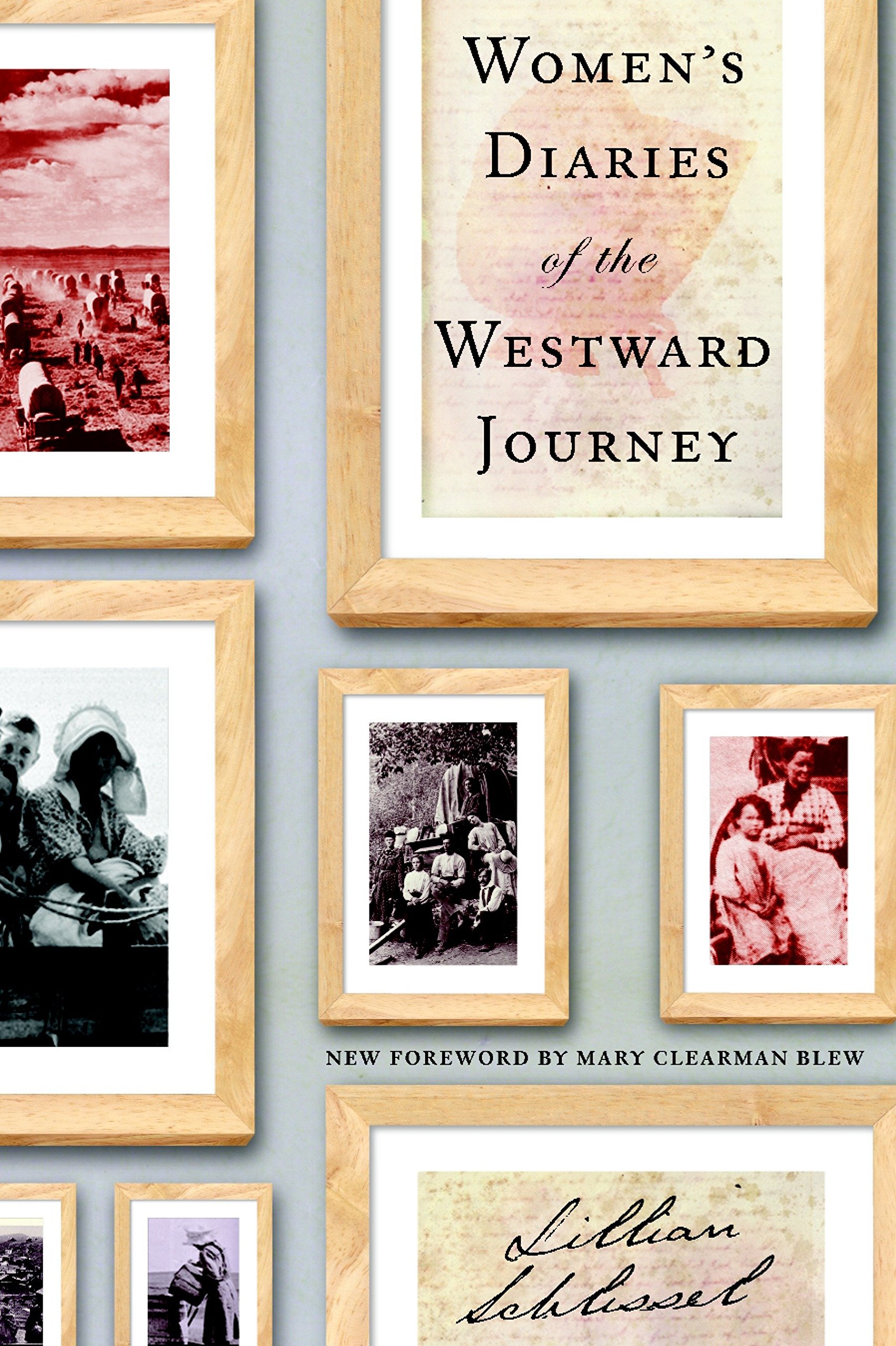

More than twenty years ago, Lillian Schlissel first made available the stories of the women who took part in the great trek on the Overland Trail between 1840 and 1870, stories told in the womens own words, through their letters, diaries, and reminiscences. For many readers, these stories were their first acquaintance with the experiences of the women who made the approximately 2,400-mile migration across the North American continent to the Oregon and California Territories in the hope of making better lives for themselves and their families. In their diaries and their letters home, the women wrote of their grief at leaving friends and family membersusually because of a decision made by a husband or a father. They described the unfamiliar landscape, they noted the details of their daily chores, they kept track of the costs of their journeys, and they tallied the dead as they passed their graves on the way west.

Historians of the Westward Movement seem only gradually to have recognized that, while westering men and women shared many of the same experiences, their points of view differed in important respects. Although in the late 1970s scholars were beginning to utilize the personal papers of the emigrants in order to assess and revise the history of the West, it was not until 1982, when Lillian Schlissel brought to vibrant life the actual words of the women who made the overland journey, that anyone had looked exclusively at womens diaries, letters, and reminiscences to see whether the womens perceptions would alter the perceptions of historians regarding the great migration.

Since 1982, regional, gender, and ethnic studies have expanded far beyond what could have been imagined twenty years ago. These studies emphasize that the story of the Westward Movement and white western settlement, which for so long has served as the national myth, is not just one story, but many stories; that in fact, the very use of terms such as movement and settlement imply a highly limited and selective point of view that is not shared by myriad Mexicans, Asians, Sioux, or Cheyennes (to name a few); and that the notion of the West as a region defined by conquest has distorted our very sense of social and geographical space. To begin reading Womens Diaries of the Westward Journey in these first years of the twenty-first century is to marvel at the prescience of Schlissels conclusions. Consider, for example, her discovery that while westering white women feared the Indians, they were much likelier than white men to describe the Indians they encountered as guides or traders than as enemies. Tribal and other historians, drawing upon oral traditions, will continue to shed new light on the complexities of converging cultures, but they will also verify Schlissels depiction of the overland experience as more quietly but perhaps more intensely dramatic than the circle the wagons scenes of hundreds of B movies.

Not all of the women who left their written records were of the same social class. Some had enjoyed more education than others. While most were married with children, a few were single (although they almost always traveled with family members). A few were black, and Schlissel has been able to identify some of these slaves and former slaves, like Mary Ellen Pleasants, who came to San Francisco in 1849 but in 1858 traveled back to eastern Canada to present John Brown with $30,000 to help free her people, or Clara Brown, who purchased her own freedom, hired on as a cook, traveled to Colorado, and started a laundry that was prosperous enough so that after the Civil War she was able to locate thirty-four long-lost relatives and bring them back with her to Denver.